| |

Abstract

Objectives: Tuberculosis is one of the oldest infections known to affect humans. The aim of the study was to assess the quality of life including physiological, general health perception and social role functioning among patients with tuberculosis in Hamadan, Western Iran.

Methods: A cross sectional analytical study was conducted between December 2009 and March 2011, the quality of life scores of 64 tuberculosis cases were measured by SF-36 questionnaire before treatment, after the initial phase and at the end of treatment and were compared with those of 120 controls. The association of the quality of life with age, type of tuberculosis, sputum smear, duration of disease, and the stage of treatment were assessed among the patients.

Results: Before treatment, all scores of tuberculosis patients were lower than those of the controls (p<0.05). The patients’ score increased significantly after two months of treatment (p=0.01), but the difference was not significant between two and six months after treatment (p=0.07). The lowest score in tuberculosis patients was related to physical functioning and energy (45 ± 42, 44 ± 24, respectively).

Conclusion: According to the results, tuberculosis patients still have a low quality of life in spite of receiving new care strategies. Therefore, enhancement in quality of life may improve adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment, functioning and well-being of patients with tuberculosis.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; SF-36 Questionnaire; Quality of life.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the oldest infections known to affect humans and in spite of the new treatment strategies and observations, it remains one of the most substantial causes of death, in the world. It is estimated that about one third of the world population has Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection.1 In 2010, there were 8.8 million new cases and 1.1 million deaths caused by TB in developing and industrialized countries.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed the Global Plan to Stop TB by 2015 and 2050, which is defined as 50% reduction in the prevalence and mortality rates by 2015 and achieving towards less than 1 case per 1 million population per year by 2050. It indicates that TB control should be more effective than it is currently.3 Besides, the burden of disease and mortality, the long duration of treatment and the combination of treatment with several agents leading to changes in life structure. However, in spite of the most focus being directed towards mortality and incidence rate, the changes in morbidity and health status parameters have not been well considered.4

There are several methods for health status and disease management evaluation. The assessment of patient reported outcomes is a valuable method for this purpose and the quality of life (QOL) instruments have been developed to measure patients’ outcome in clinical research and practice.5 The QOL is defined as individuals’ perception of their physical and mental health in their daily lives which cover physical, psychological, economic, spiritual, and social functioning.6 It can reflect the impact of diseases and related morbidities on daily activities and functioning. This measurement is more necessary among patients with a chronic disease whose mental and social well-being as well as pure physical health are affected by the disease and its related long-term treatment.4 Therefore, it is required to investigate the QOL of TB patients to recognize appropriate actions for improvement of health status and the QOL among the patients.7

In addition, just the diagnosis of TB alone may lead to depression and anxiety or contribute to the worsening and persistence of disease symptoms, which follows with fear, frustration, and disappointment.8 Furthermore, most TB patients have no knowledge of disease progress and treatment which can cause more anxiety and feelings of frustration and decreases the QOL among the patients.9 Studies focusing on the QOL among TB patients are limited and no such investigation has been conducted among the Iranian population. Considering the fact that improvement in health-related QOL is an important factor for better response to treatment among TB patients, which may lead to better outcome in patients’ mental health, infection surveillance and prevention programs as well as location of Iran. On the other hand, as an endemic country for TB and no previous study on QOL of TB patients has been conducted in Iran, this study was designed to assess the QOL among TB patients living in Hamadan, a TB-endemic province, Western Iran, and compare the findings with the QOL among a healthy population taken as controls from the same area.

Methods

A cross sectional analytical study was conducted in Hamadan, Westrn Iran between December 2009 and March 2011. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. All participants signed an informed consent before entering into the study. Since the total number of patients who entered into the Provincial TB Clinic in Hamadan city during the research period were almost similar to the sample size; therefore, the first 64 patients attending the TB clinic were selected in that period if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. For selection of the control group, 120 random numbers were chosen and were assigned to people who consecutively entered into the Blood Transfusion Organization clinic.

The QOL measures were administered by trained investigators to the participants. TB patients completed these measures at the baseline, two months, and six months during their regular scheduled visits. Data for the study were collected by in-person interviews which were done by trained interviewers. All participants were interviewed face-to-face in completing the study QOL measures. Before study enrolment, all individuals were informed about the voluntary nature of participation and confidentiality as well as the use of their data for research purposes only. Also, the confidentiality of the participants’ data was ensured by the lack of any identifying personal information. A two-part questionnaire including demographic data for the first part and the QOL questionnaire for the second part were designed. All TB patients answered the additional questions about their disease in the first part which included clinical type of TB (with pulmonary [smear positive and negative] and extra pulmonary tuberculosis diseases according to the WHO definitions for TB),2 and the course of treatment (baseline, two months, and at the end of treatment). The second part consisted of 36 items short form SF-36 questionnaire to determine health-related quality of life.

The validity and reliability of the SF-36 questionnaire has previously been studied.10 The SF-36 questionnaire has been previously translated, validated, and standardized for the Iranian people (Persian version) by Montazeri et al.11 This questionnaire contains eight categories assessing diverse concepts of health including physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health, energy, social functioning, and emotional domain and mental health. In addition, certain domains can be aggregated to create the total QOL measures. For all the SF-36 categories and summary scores, higher scores indicate better health.

All statistical analyses were done using SPSS, version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). To compare variables, Chi-square and one-way ANOVA tests were used. Moreover, Pearson correlation was used to determine the association between continuous quantitative variables, and also the Spearman correlation was used to assess the relation between QOL scores and ordinal variables. Repeated measure analysis was done for comparing QOL of TB patients at different time points. Finally, linear regression analysis was used for adjustment of some confounding variables. All hypotheses tests were 2-tailed with p<0.05 considered as significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and frequency and percentages for qualitative variables.

Results

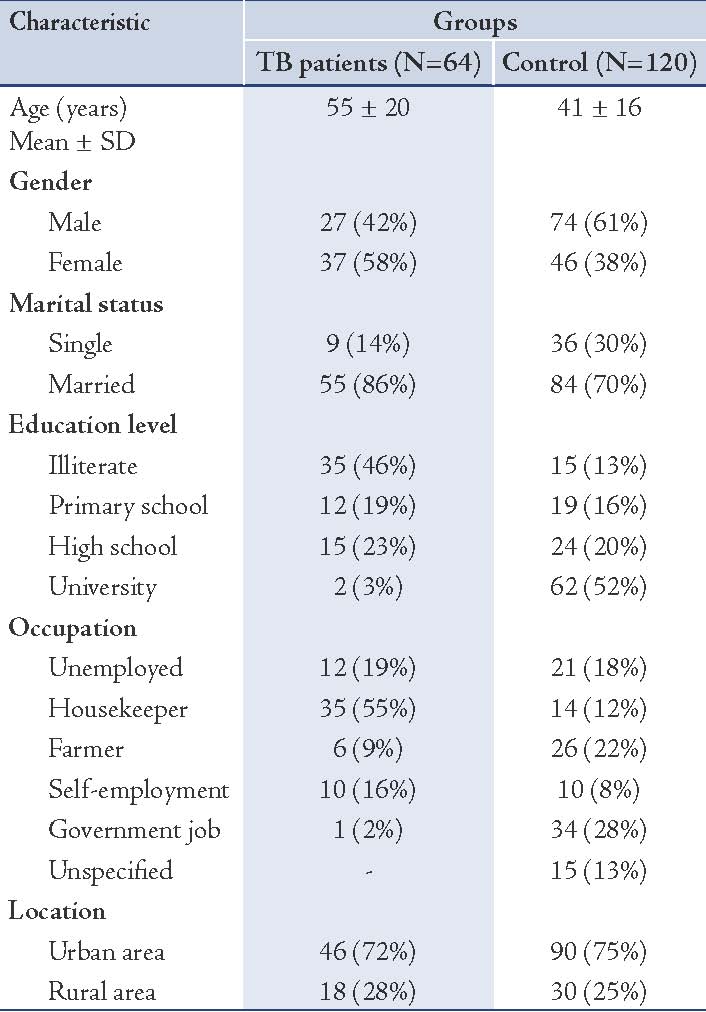

In this study, 64 cases with TB and 120 healthy controls were enrolled. The mean age was 55 ± 20 and 41 ± 16 years in the cases and controls, respectively. Totally, 37 cases (58%) and 46 controls (38%) were female. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics data between the two groups. In the case group, 46 patients (72%) had pulmonary and 18 (28%) had extra-pulmonary TB. There were 31 (48%) smear positive pulmonary TB among the case group.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the patients with TB and control group.

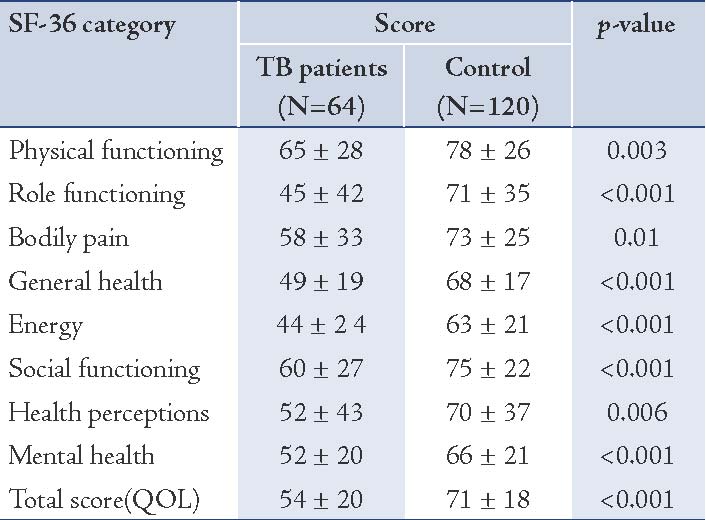

Baseline QOL was compared between cases and controls according to the SF-36 questionnaire. Table 2 shows this comparison and indicates the mean of SF-36 categories as well as the overall QOL score among the patients and the control group (at the baseline). The mean score of the QOL was 54 ± 20 and 71 ± 18 for the case and control groups, respectively. Overall, the QOL among TB patients at the onset of treatment was significantly lower than the healthy participants (p<0.001). The same difference was seen even after adjusting the subjects in terms of age, sex, marriage, education and type of disease using linear regression (p<0.001). The minimum score of SF-36 category among the two groups was related to energy category which was 44 ± 24 and 63 ± 21 for the cases and the controls, respectively. There were significant differences between the two groups in the eight categories of SF-36 scores, p<0.05. (Table 2)

Table 2: Comparison of eight SF-36 category scores between the TB patients and the control group.

The QOL of TB patients was assessed at two-months as well as at six-months after treatment with four-drug TB regimens. Overall, QOL score was 59 ± 18 and 63 ± 19 at two and six months after anti-tuberculosis treatment, respectively. The "Repeated Measure" test was used for inter-groups data at different time-points (0, 2, and 6 months after onset of treatment). This test indicated that the QOL of TB patients was significantly improved at two months after treatment (p=0.01). However, there was no statistical difference between the second and sixth months of TB treatment (p=0.07).

Discussion

This study was conducted on 64 TB patients and their QOL scores were measured by SF-36 questionnaire and compared with 120 healthy individuals living in the same area. The study indicated that the QOL of TB patients in all eight categories was significantly lower than that of the control population. Between 2003 and 2004, Duyan et al. performed a study on 120 TB patients hospitalized in Atatürk Lung Diseases and Chest Surgery Hospital in Turkey. They found that TB diagnosis was associated with changes in family life and social environment leading to a negative impact on the patients’ QOL.12 Another study in Turkey by Unalan et al. was conducted on 196 active and 108 inactive TB patients which were compared with 196 controls. The study showed that the rate of depression was higher among TB patients than the control group and the severity of depression was negatively correlated with QOL.13

In this study, the QOL of TB patients was measured in three phases: at the onset of treatment, at two months, and six months after the initiation of anti-tuberculosis therapy. The results showed that the QOL was significantly increased after two months which indicated the positive impact of the four-drug TB regimens on the improvement of the QOL in these patients. However, there was no difference between the second and third phases of the QOL measurements. Chamal et al.7 in China conducted a study on 102 TB patients and assessed the QOL before treatment, after the initial phase, and at the end of treatment and compared them with 103 controls. They found that the QOL score of TB patients was low before the treatment and increased during the treatment course that was similar to the results of the current study. Although the QOL improved over the anti-TB treatment period, the overall QOL score at the end of six months remained lower than the general population. A systematic review published in 2009, demonstrated that TB patients in several studies had a lower QOL than the healthy population even after treatment.5

The reason for the low QOL even after six months anti-TB treatment may be related to psychological outcome of the disease due to isolation from the community and family life based on the contagious nature of TB infection, which also may lead to depression among TB patients. A study in Pakistan was carried out on 60 TB patients and showed that 80% of them were depressed. The study concluded this high rate of depression among TB patients was due to lower socioeconomic status, long treatment period, stigmatic nature of the disease, as well as fear and threat concerning the risk of transmitting infection from air-borne bacteria which all lead to decrease in resistance against the infection and response to the treatment which was followed by isolation and disappointment of the patient.14

On the other hand, six-months treatment with potentially toxic agents may lead to anti-TB related side effects such as isoniazid-induced liver dysfunction or leukopenia due to rifampicin which may cause the QOL impairment. Wang et al. showed that the QOL of pulmonary TB patients decreased when compared to the general population and its associated factors included focus size of infection, counts of white blood cells, complications, elevated ALT and the duration of disease.15 Therefore, a better QOL in TB patients can be achieved with proper information about the disease, route and condition of its transmission as well as periodical laboratory evaluations and repeated examinations over the treatment course to perform appropriate actions after drug complications.

There are some limitations in the present study that may have some potential impacts on the results. All prognostic features such as co-morbidities were not included in the analysis. In addition, for comparing of QOL between two groups, it would have been better to conduct a pure analytical study; however, this study (comparative cross sectional study design) is also useful for analysis of this comparison.

Conclusion

The study yeilded low QOL scores among TB patients, in spite of new therapeutic and surveillance strategies, and it is concluded therefore, that more attention should be focused on QOL improvement in order to improve response to the treatment and decrease the rate of drug failures as well as improvement of mental and physical functioning among TB patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Tahereh Doroozi, the staff at Health Center of Hamadan and Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization in Hamadan for their contributions in this research. No conflict of interest to be declared.

References

1. Marra CA, Marra F, Colley L, Moadebi S, Elwood RK, Fitzgerald JM. Health-related quality of life trajectories among adults with tuberculosis: differences between latent and active infection. Chest 2008 Feb;133(2):396-403.

2. Report WH. 2011: Global Tuberculosis Control. WHO Web Site; 2011[updated 15January 2013]; Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/en/index.html

3. Lienhardt C, Espinal M, Pai M, Maher D, Raviglione MC. What research is needed to stop TB? Introducing the TB Research Movement. PLoS Med 2011 Nov;8(11):e1001135.

4. Dion MJ, Tousignant P, Bourbeau J, Menzies D, Schwartzman K. Feasibility and reliability of health-related quality of life measurements among tuberculosis patients. Qual Life Res 2004 Apr;13(3):653-665.

5. Guo N, Marra F, Marra CA. Measuring health-related quality of life in tuberculosis: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:14.

6. Kaplan RM, Ries AL. Quality of life: concept and definition. COPD 2007 Sep;4(3):263-271.

7. Chamla D. The assessment of patients’ health-related quality of life during tuberculosis treatment in Wuhan, China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004 Sep;8(9):1100-1106.

8. Peterson Tulsky J, Castle White M, Young JA, Meakin R, Moss AR. Street talk: knowledge and attitudes about tuberculosis and tuberculosis control among homeless adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1999 Jun;3(6):528-533.

9. Salomon N, Perlman DC, Friedmann P, Perkins MP, Ziluck V, Jarlais DC, et al. Knowledge of tuberculosis among drug users. Relationship to return rates for tuberculosis screening at a syringe exchange. J Subst Abuse Treat 1999 Apr;16(3):229-235.

10. Dion MJ, Tousignant P, Bourbeau J, Menzies D, Schwartzman K. Feasibility and reliability of health-related quality of life measurements among tuberculosis patients. Qual Life Res 2004 Apr;13(3):653-665.

11. Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res 2005 Apr;14(3):875-882.

12. Duyan V, Kurt B, Aktas Z, Duyan GC, Kulkul DO. Relationship between quality of life and characteristics of patients hospitalised with tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005 Dec;9(12):1361-1366.

13. Unalan D, Soyuer F, Ceyhan O, Basturk M, Ozturk A. Is the quality of life different in patients with active and inactive tuberculosis? Indian J Tuberc 2008 Jul;55(3):127-137.

14. Anwar Sulehri M, Ahmad Dogar I, Sohail H, Mehdi Z, Azam M, Niaz O, et al. Prevalence of depression among tuberculosis patients. Annals of Punjab Medical College. 2010;4:133-137.

15. Wang Y, Lii J, Lu F. [ Measuring and assessing the quality of life of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 1998 Dec;21(12):720-723.

|