|

Introduction

Megaureter is defined as dilated ureter with or without dilatation of the renal pelvis and calyces. It is sporadic or familial, bilateral in 20% with the left side more commonly affected, and with male to female ratio of 4:1.1 It can be primary (congenital) or secondary, with the commonest cause of secondary megaureter being bladder outlet obstruction associated with elevated bladder pressure. In primary obstructive megaureter, the obstruction is due to an adynamic juxtavesicle segment of the ureter that fails to propagate urine flow.2

Primary megaureter is rare in adults. The diagnostic criteria include dilated ureter, absence of vesicoureteral reflux, absence of infravesical obstruction, and absence of distal ureteral obstruction.3 Although a rare condition in adults, it typically occurs during the third or fourth decade and may present when kidney stones develop as a result of the ureteral abnormality.4

Case Report

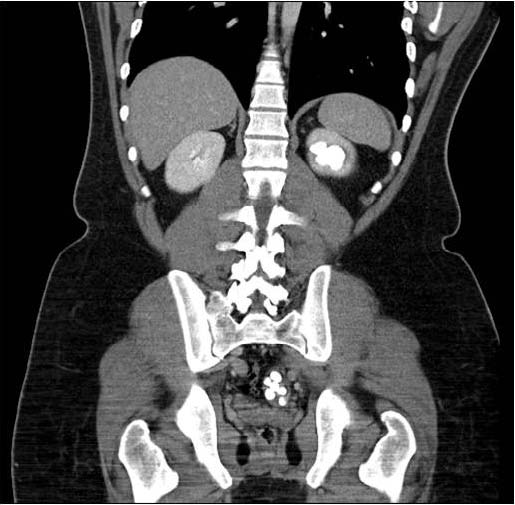

A 24-year-old male presented with frank hematuria on exercise of 4 years duration. He gave a history of renal stones, eating meat frequently and smoking. He had no history of other urinary or bowel symptoms, and no comorbidities or surgeries. Physical examination was normal apart from extreme obesity with body mass index of 46 kg/m2. Investigations revealed normal CBC, renal function, electrolytes, coagulation, and LFT. Urine analysis showed 40 RBC, 20 WBC and no growth on urine culture. Ultrasound of abdomen and IVU (intravenous urogram) showed multiple left renal stones with hydronephrosis and delayed function (Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, the left ureter was dilated, which was packed with multiple stones at its lower end. The right kidney and bladder were normal. Non-enhanced CT of abdomen revealed a left lower ureter with 2.8 cm in diameter containing multiple stones causing dilatation of the ureter proximally with periureteral fat stranding. (Fig. 3)

Figure 1: KUB showing multiple stones in the left kidney and lower left ureter.

Figure 2: IVU showing multiple stones in the dilated left ureter.

Figure 3: CT scan of abdomen showing multiple stones in the left kidney and lower left ureter.

The largest stone measured 1.5 cm. In addition, there were multiple renal calculi noted in the superior and inferior calyces of the left kidney. The right kidney, however, was normal in size, shape, and contour with no evidence of hydroureter, hydronephrosis or vesical stones. Renogram scintigraphy (Tc-99m MAG-3 dose 268 MBq) showed a baseline right kidney with good perfusion, uptake, and delayed excretion, as well as a relative function of 50%. The left kidney was enlarged and showed reduction in perfusion and uptake, no excretion, dilated calyces and dilated ureter with a relative function of 50%. Post-Lasix, there was poor washout of radiotracer from the left kidney suggestive of obstruction, whereas the right kidney had good function with no obstruction. The preserved function of the left kidney could be explained by diagnosing the patient at a stage before atrophy and reduction of renal parenchyma has occurred.

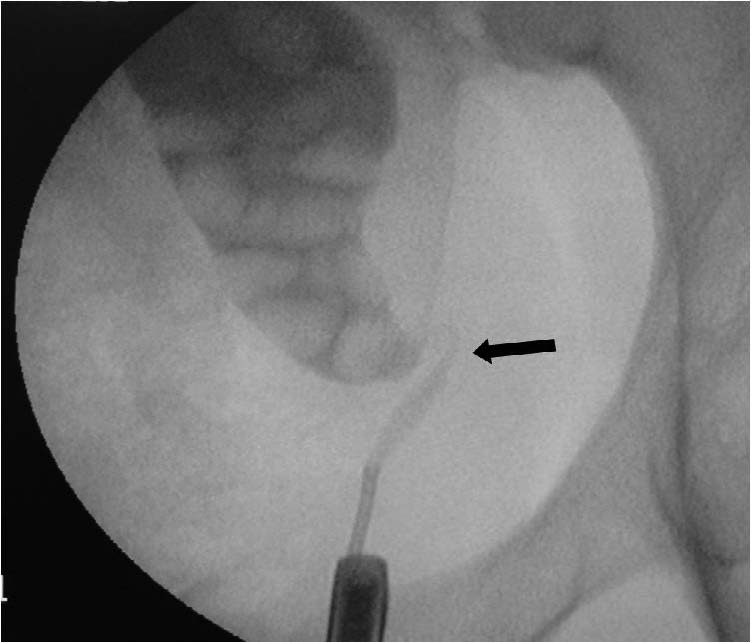

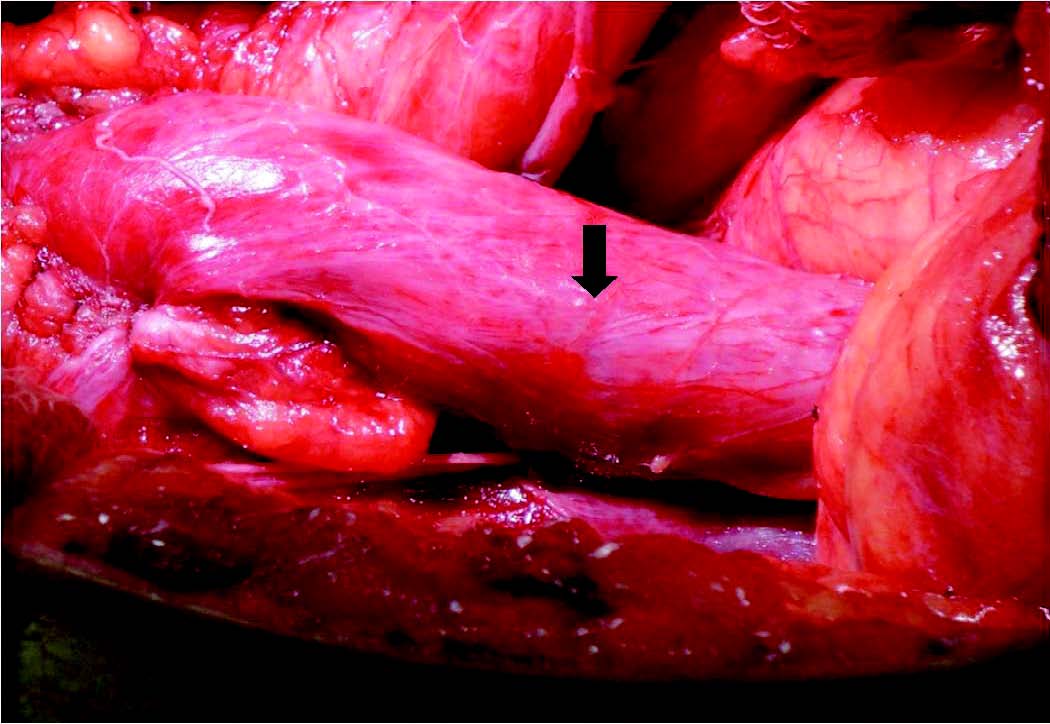

The patient underwent cystoscopy and left retrograde pyelography that revealed normal bladder with no bladder outlet obstruction, stenotic distal lower left ureter with huge dilatation beyond it with multiple renal stones (Fig. 4). The patient then had an open surgery in the form of left ureteric re-implantation (refluxing, non-tapering) and removal of the ureteric and renal stones (Fig. 5). There were 11 smooth surfaced, grey-colored stones delivered from the left ureter. The renal stones were removed with the aid of a flexible cystoscope, which was introduced through the open ureter up to the renal pelvicalyceal system. All calices were inspected and 7 more stones were removed using graspers and baskets after being broken by Holmium laser. (Fig. 6)

Stone analysis revealed combined uric acid-oxalate lithiasis with predominant uric acid structure (60% anhydrous uric acid, 40% monohydrate calcium oxalate). On follow-up, the patient had ESWL (extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy) for the residual left lower calyx kidney stone which was partially fragmented and the DJ (double-J) stents were subsequently removed. A 6-month post surgery renogram revealed the right kidney to have good function with no obstruction and relative function of 59%. The left kidney had moderately poor function with partial obstruction and relative function of 42%. The patient was scheduled more ESWL sessions for the remaining left lower calyx renal stone and follow-up with renogram. His renal function remained normal on follow-up and was free of infection.

Figure 4: Retrograde pyelography showing a stenotic segment (black arrow) of the left lower ureter above which is a dilated ureter packed with stones.

Figure 5: Intraoperative picture showing the hugely dilated ureter (black arrow) resembling a bowel segment.

Figure 6: Stones removed from the left kidney and ureter (Combined uric acid-oxalate lithiasis)

Discussion

Structurally, normal ureteral diameter is rarely greater than 5 mm and ureters wider than 7 to 8 mm can all be considered megaureters. The current belief is that primary obstructive megaureter presents primarily in adults when the congenital abnormality does not cause symptoms or illness and is not seen by imaging study performed during childhood. Spontaneous regression fails to occur, yet patients remain asymptomatic through childhood and into their adult years. Eventual symptoms that may occur include urinary tract infections, renal parenchymal damage and recurrent stone formation. In the largest reported series of 55 adults and adolescents with symptomatic primary obstructive megaureter, Hemal and colleagues identified 20 patients (36%) as having urinary tract calculi.5 Most of the calculi were located in the ureter; only 3 (5%) of the 55 patients had renal calculi without calcification near the location of the underlying abnormality (distal ureter).

Large stones can develop in the dilated portion of the ureter due to stasis of urine. Delakas and colleagues described an adult patient with primary megaureter who developed a 12-cm urinary calcification within the dilated portion of the ureter.6 Giant megaureter can massively distend the abdomen and present as cystic mass.7 Megaureter may be associated with unilateral renal agenesis, duplex system, ectopic kidney, contralateral cystic and dysplastic kidney, horseshoe kidney, or Hirschsprung disease.8 In addition, primary obstructive megaureter has been reported to present with ruptured kidney.9

Conclusion

Congenital megaureter is a diagnosis that urologists and radiologists need to consider in cases of isolated distal ureteral dilation, as the diagnosis of adult megaureter may require more involved surgical measures to prevent recurrence of adverse symptoms. In the present case, we present a novel technique of using retrograde access in an open surgery that has helped to achieve a near complete stone clearance. In our patient, the risk factors for developing renal stones include extreme obesity and high protein diet. The diagnosis of primary obstructive megaureter was based on exclusion of bladder outflow obstruction and reflux. Long follow-up of this patient was needed as his left kidney function was reduced due to chronic pyelonephritis. Robotic repair and removal of ureteric stones in primary symptomatic obstructive megaureter has been reported to be safe, feasible, and effective with either intracorporeal or extracorporeal ureteric tapering.10

Acknowledgements

The authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding was received for this work.

References

1. Hanna MK, Jeffs RD. Primary obstructive megaureter in children. Urology 1975 Oct;6(4):419-427.

2. Gosling JA, Dixon JS. Functional obstruction of the ureter and renal pelvis. A histological and electron microscopic study. Br J Urol 1978 May;50(3):145-152.

3. Khoury A, Bagli DJ. Reflux and Megaureter. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc; 2007. pp. 3467-81.

4. Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Gupta NP, Wadhwa SN. Primary obstructive megaureter in adults: need for an aggressive management strategy. Int Urol Nephrol 1999;31(5):633-641.

5. Hemal AK, Ansari MS, Doddamani D, Gupta NP. Symptomatic and complicated adult and adolescent primary obstructive megaureter–indications for surgery: analysis, outcome, and follow-up. Urology 2003 Apr;61(4):703-707, discussion 707.

6. Delakas D, Daskalopoulos G, Karyotis I, Metaxari M, Cranidis A. Giant ureteral stone in association with primary megaureter presenting as an acute abdomen. Eur J Radiol 2002 Feb;41(2):170-172.

7. Saurabh G, Lahoti BK, Geetika P. Giant megaureter presenting as cystic abdominal mass. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2010 Jan;21(1):160-162.

8. Wood BP, Ben-Ami T, Teele RL, Rabinowitz R. Ureterovesical obstruction and megaloureter: diagnosis by real-time US. Radiology 1985 Jul;156(1):79-81.

9. Chung SD, Sun HD, Yang DK, Liao CH. Primary obstructive megaureter with ruptured kidney. Am J Emerg Med 2009 Jan;27(1):e5-e6.

10. Hemal AK, Nayyar R, Rao R. Robotic repair of primary symptomatic obstructive megaureter with intracorporeal or extracorporeal ureteric tapering and ureteroneocystostomy. J Endourol 2009 Dec;23(12):2041-2046.

|