|

Abstract

Objectives: Burnout is a common work-related syndrome consisting of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and diminished feelings of personal accomplishment. Burnout influences the performance and efficiency of the healthcare professionals and therefore the quality of the care provided. This study aims to assess the burnout rates and potential determinants in pediatrics.

Methods: A cross-sectional, descriptive study involving physicians practicing pediatrics in the Jeddah area of Saudi Arabia was conducted utilizing the Maslach Burnout Inventory in addition to questions regarding work-related and lifestyle-related factors.

Results: One hundred and thirty pediatricians (55% females) were included with age ranging between 25 and 45 years (mean: 30). Most (46%) were consultants and 54% practiced in a university based setting. Burnout scores were abnormal in 107 (82%) and in 45 (34%) the syndrome was severe. Males were more likely to reach a severe burnout category compared to females (40% vs. 31%; p=0.012). Academic pediatricians working in a university setting were much more likely to experience severe burnout compared to their counterparts working in other hospitals (50% vs. 19%; p=0.0005). Consultants were also more likely to experience severe burnout compared to residents and assistants (46% vs. 27%; p=0.03).

Conclusion: At least one third of practicing pediatricians suffer from burnout syndrome. Specific strategies should be developed and implemented to limit and prevent professional burnout.

Keywords: Burnout Syndrome; Pediatrics; Child; Practice.

Introduction

Burnout is a common work-related syndrome consisting of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and diminished feelings of personal accomplishment.1-3 Affected individuals are unable to cope with emotional stress at work with negative, cynical feelings and attitudes toward their colleagues and patients. They often feel unsatisfied with their work and accomplishments.4 The prevalence of burnout syndrome is higher in professions that are physically demanding or those requiring higher levels of commitments with stressful work environment.5 Examples of these situations include supervisory positions, surgical or procedural services; and intensive or emergency care services.6-8 All these situations frequently apply to pediatricians working in various services. Some pediatric subspecialties can be more emotionally draining than others including nephrology, oncology, and neurology.8-10 Pediatricians have to deal with children who have chronic incurable conditions associated with multiple problems. They have to interact with their stressed and often fatigued parents. Burnout state influences the performance and efficiency of the healthcare professional and therefore affects the quality of the care provided often unconsciouly.11 Providing such quality medical services is quite costly and therefore such problems could have significant implications.12 Studies on the issues of burnout syndrome have been very limited, particularly in our region. The purpose of this study is to assess the burnout rates and potential determinants of burnout in a sample of practicing pediatricians. We hypothesize that many pediatricians are suffering from burnout syndrome, thus we plan to explore the contributing and correlating factors of burnout state in order to alleviate its effects and help improve the work environment.

Methods

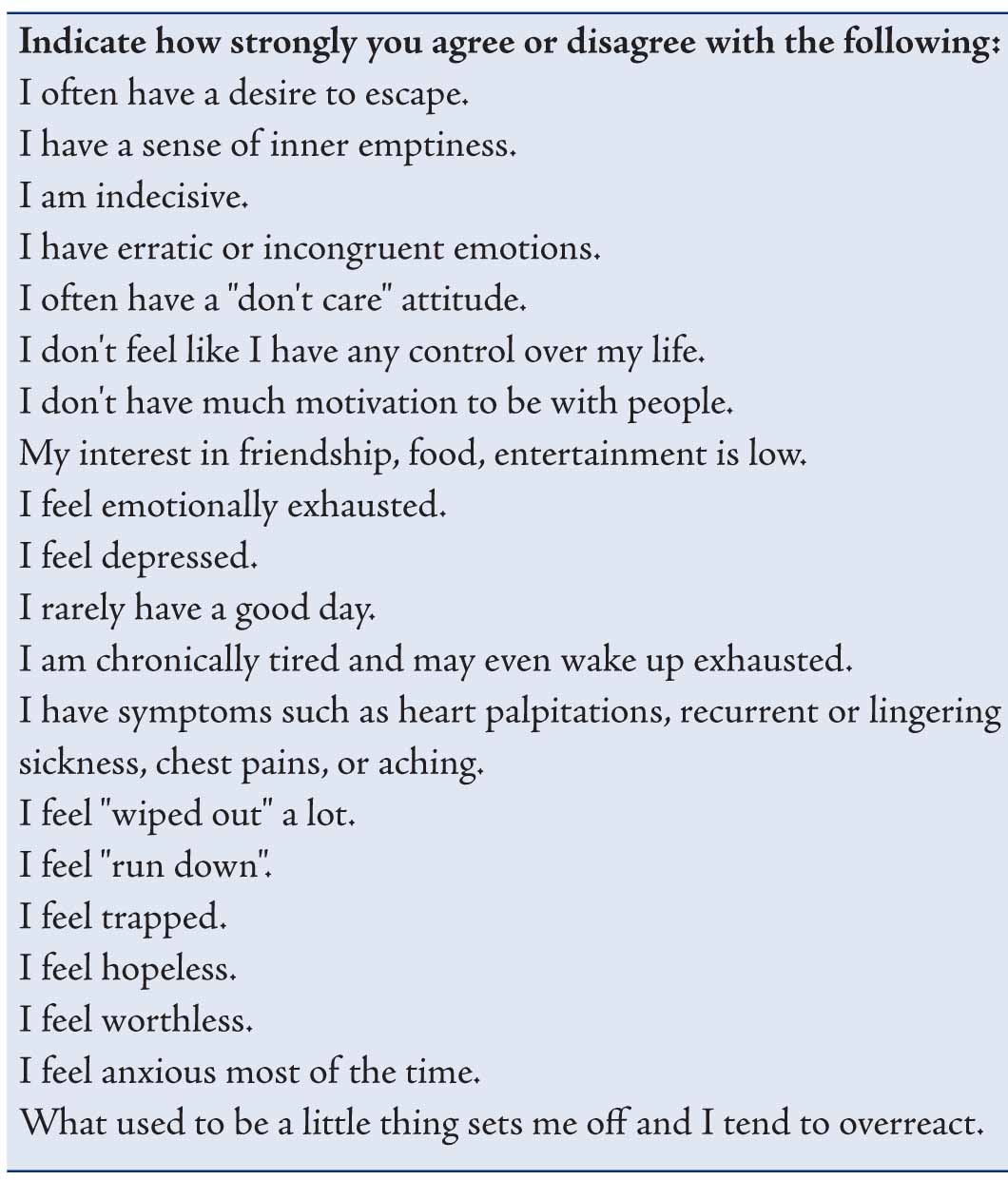

A cross-sectional, descriptive study involving pediatric physicians in the Jeddah area of Saudi Arabia was conducted over 3 consecutive months, in 2010. Pediatricians at various levels were enrolled into the study including residents, assistants, and consultants. They practiced pediatrics at various major hospitals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, including university, private, military and service hospitals. Burnout symptoms and their severity were evaluated using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which examines three domains including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization symptoms and level of personal accomplishment at work.4 The original English version was used and examples of key questions are listed in table 1.

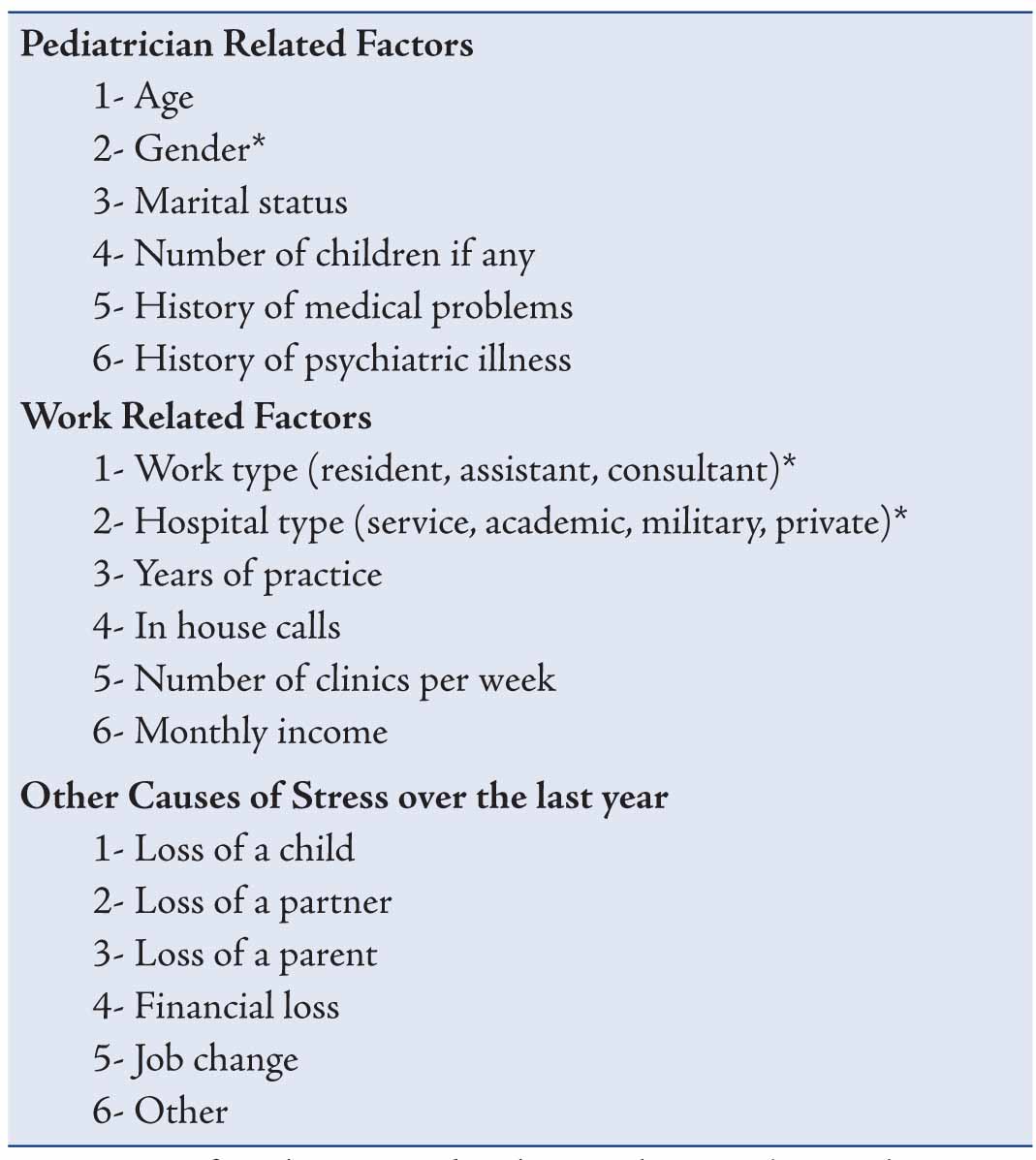

Table 1. Demographics, as well as questions based on work-related and lifestyle-related factors associated with developing burnout syndrome were included (Table 2). King Abdulaziz University hospital ethics committee approved the study design and questionnaires. One author personally distributed the questionnaires (hand to hand) to maximize the response rate and subsequently collected the data. Before consenting for the study, all participants were assured that the study is completely voluntary and the provided information will remain confidential.

Statistical analysis of the data was done using SPSS 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive analyses were performed and the variables were examined using chi-square test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Table 1: Key question included in the burnout inventory.

Results

Two hundred questionnaires were distributed and 130 (65%) were returned. Of these, 130 pediatricians, 55% were females with age ranging between 25 and 45 years (mean±SD: 30±5). Most of the pediatricians (72%) were married and 53% had children ranging in number from 1-11 (2±2.4). The study participants were comprised of consultants (46%), residents (31%) and assisstants (23%) who completed their pediatric training. All participants were practicing in various pediatric disciplines with years of practice ranging between 1 and 32 years (10±9). The majority (54%) practiced in either an academic or university based setting with varying monthly income.

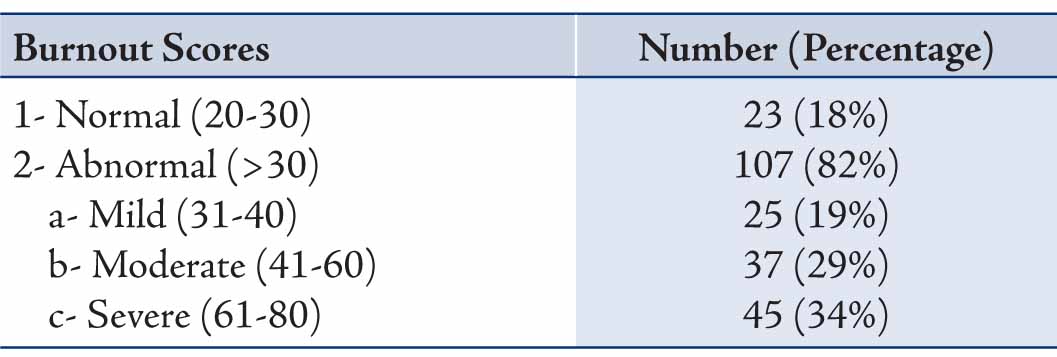

The burnout scores were abnormal in 107 (82%) of the included pediatricians and were significantly abnormal (severe) in 45 (34%) as shown in Table 3. Three of the examined variables correlated with burnout status were as follows: gender, job category and hospital setting (Table 2). Males were more likely to reach a severe burnout category compared to females (40% vs. 31%; p=0.012). Academic pediatrician working in a university setting were much more likely to have severe burnout compared to those working at other hospitals (50% vs. 19%; p=0.0005). Finally, consultants were more likely to experience severe burnout compared to residents and assistants (46% vs. 27%; p=0.03). Age, marital status, years of practice, and income had no correlation with burnout status. Also, the number of in-house calls and clinics per week had no significant correlations. The results also showed that 19% of the participants had other significant stresses in their lives (Table 2); however, this factor was not reflected in their burnout scores. This was also true for those with history of other medical (24%) or psychiatric (3%) illnesses.

Table 2: List of factors that were assessed to correlate with severe burnout.

Table 3: Burnout scores and their severity among the study sample (n=130).

Discussion

This study documented that at least one third of pediatricians practicing in the Jeddah region are suffering from burnout syndrome. This is a chronic adaptation disorder that provokes serious problems in occupational behavior. Few other studies have assessed the prevalence of burnout syndrome among pediatric healthcare workers.13-15 Franco et al. found that burnout syndrome was present in 41% of hospital workers attending pediatric patients, which is similar to our findings.14 In our study, males, consultants, and those occupying academic positions were at a particular risk. To the contrary of our findings, females were at a higher risk of developing burnout (47% vs. 32%) in a pediatric oncology study.8 This may be explained by the stressful nature of the oncology subspecialty that frequently deals with life threatening illness. Females in general favor pediatrics and tend to select it as a career choice more than males.16 This may be reflected on their job satisfaction and therefore lower their risk for burnout syndrome. In another study, burnout was higher as pediatricians revealed more years of professional performance.15 This trend was not encountered in the current study; however, consultants were more likely to experience burnout compared to more junior physicians. Increased responsibilities may explain this trend rather than simply the years of practice. The high burnout levels among the academic pediatricians can be explained by the increased burden of work that encompasses teaching, program developments and periodic exams. Though this trend has not been previously reported. One previous study based around medical residents in a teaching hospital revealed their increased risk for burnout.17

In addition the results revealed no correlation between burnout status and age, marital status, work load, as well as income. Those with other significant stresses in their lives were not at an increased risk of burnout. Furthermore, practicing general pediatrics versus subspecialty did not affect burnout status, hence the lack of significant associations may be related to the relatively small sample size. Other studies have documented increased burnout syndrome in certain subspecialties such as, neurology, oncology and pediatric intensive care.6,8,9 In a population-based survey, 50% of pediatric intensivists were at risk of burnout.6 This is easily explained by the nature of such practice and work schedule. In another study, 38% of pediatric oncologists were reported to have high levels of burnout as a result of dealing with children at risk of dying.8 Finally, Horiguchi et al. assessed physicians working in pediatric neurology using a burnout inventory and a general health questionnaire and found that 27% of the respondents had attained a burnout status and 93% were suffering from stress related neurosis.9

Based on the current study and all reviewed literature, burnout is a significant problem that must be addressed and highlighted in the pediatric work environment. Specific strategies should be developed and implemented to limit and prevent professional burnout, keeping in view its effect on patient safety. This is particularly relevant in our region where this problem has not been well studied.18,19 In one study, it was revealed that burnout in pediatrics had significant negative implications including conflict with the managing policy, poor work satisfaction and some respondents even considered leaving their job in the future.13 Pediatricians may develop negative attitudes toward self and professional activity, and eventually lose interest in pediatric care, have low productivity and diminished self-esteem. Several facts can be used to develop such strategies. Routine exercise (a strategy used by some for stress reduction) was associated with lower burnout scores.6 Physicians who reported satisfaction with their lives outside of work were less likely to have burnout.8 Therefore, social and community involvement should be encouraged. The availability of a forum for debriefing, and services for pediatricians affected by burnout were both associated with lower rates of burnout.8 Further research is needed on the development, implementation and effectiveness of interventions aimed at preventing and treating work-related burnout.

Conclusion

We conclude that at least one third of pediatricians practicing in the Jeddah region are suffering from burnout syndrome. Specific strategies should be developed and implemented to limit and prevent professional burnout.

Acknowledgements

The authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding was received for this work.

References

1. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 2001;52:397-422.

2. Teng CI, Chang SS, Hsu KH. Emotional stability of nurses: impact on patient safety. J Adv Nurs 2009 Oct;65(10):2088-2096.

3. Della Valle E, De Pascale G, Cuccaro A, Di Mare M, Padovano L, Carbone U, et al. [Burnout: rising interest phenomenon in stressful workplace]. Ann Ig 2006 Mar-Apr;18(2):171-177.

4. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav 1981;2:99-113 .

5- Lesic AR, Stefanovic NP, Perunicic I, Milenkovic P, Tosevski DL, Bumbasirevic MZ. Burnout in Belgrade orthopaedic surgeons and general practitioners, a preliminary report. Acta Chir Iugosl 2009; 56:53-59.4

6. Fields AI, Cuerdon TT, Brasseux CO, Getson PR, Thompson AE, Orlowski JP, et al. Physician burnout in pediatric critical care medicine. Crit Care Med 1995 Aug;23(8):1425-1429.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt T. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg 2010;44:29-47.

8- Roth M, Morrone K, Moody K, Kim M, Wang D, Moadel A, Levy A. Career burnout among pediatric oncologists. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011; 15;57(7):1168-73.

9. Horiguchi T, Kaga M, Inagaki M, Uno A, Lasky R, Hecox K. An assessment of the mental health of physicians specializing in the field of child neurology. J Pediatr Nurs 2003 Feb;18(1):70-74.

10. Jan MM. Perception of pediatric neurology among non-neurologists. J Child Neurol 2004 Jan;19(1):1-5.

11. Reader TW, Cuthbertson BH, Decruyenaere J. Burnout in the ICU: potential consequences for staff and patient well-being. Intensive Care Med 2008 Jan;34(1):4-6.

12. Al Rashdi I. How much the quality of healthcare costs? A challenging question! Oman Med J 2011 Sep;26(5):301-302.

13. Bustinza Arriortua A, López-Herce Cid J, Carrillo Alvarez A, Vigil Escribano MD, de Lucas García N, Panadero Carlavilla E. [Burnout among Spanish pediatricians specialized in intensive care]. An Esp Pediatr 2000 May;52(5):418-423.

14. López Franco M, Rodríguez Núñez A, Fernández Sanmartín M, Marcos Alonso S, Martinón Torres F, Martinón Sánchez JM. [Burnout syndrome among health workers in pediatrics]. An Pediatr (Barc) 2005 Mar;62(3):248-251.

15. Pistelli Y, Perochena J, Moscoloni N, Tarrés MC. [Burnout syndrome among pediatricians. Bivariate and multivariate analysis]. Arch Argent Pediatr 2011 Apr;109(2):129-134.

16. al-Asnag MA, Jan MM. Influence of the clinical rotation on intern attitudes toward pediatrics. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2002 Sep;41(7):509-514.

17. Ringrose R, Houterman S, Koops W, Oei G. Burnout in medical residents: a questionnaire and interview study. Psychol Health Med 2009 Aug;14(4):476-486.

18. Al-Turki HA. Saudi Arabian Nurses. are they prone to burnout syndrome? Saudi Med J 2010 Mar;31(3):313-316.

19. Sadat-Ali M, Al-Habdan IM, Al-Dakheel DA, Shriyan D. Are orthopedic surgeons prone to burnout? Saudi Med J 2005 Aug;26(8):1180-1182.

|