|

Abstract

Objectives: Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is a major clinical and public health problem, both for diagnosis and management. We compare two established scoring systems, Thwaites and the Lancet consensus scoring system for the diagnosis of TB and compare the clinical outcome in a tertiary care setting.

Methods: We analyzed 306 patients with central nervous system (CNS) infection over a 5-year period and classified them based on the unit’s diagnosis, the Thwaites classification as well as the newer Lancet consensus scoring system. Patients with discordant results-reasons for discordance as well as differences in outcome were also analyzed.

Results: Among the 306 patients, the final diagnosis of the treating physician was TBM in 84.6% (260/306), acute CNS infections in 9.5% (29/306), pyogenic meningitis in 4.2% (13/306) and aseptic meningitis in 1.3% (4/306). Among these 306 patients, 284 (92.8%) were classified as "TBM" by the Thwaites" score and the rest as "Pyogenic". The Lancet score on these patients classified 29 cases (9.5%) as 'Definite-TBM', 43 cases (14.1%) as "Probable-TBM", 186 cases (60.8%) as "Possible-TBM" and the rest as "Non TBM". There was moderate agreement between the unit diagnosis and Thwaites classification (Kappa statistic = 0.53), as well as the Lancet scoring systems. There is only moderate agreement between the Thwaites classification as well as the Lancet scoring systems. It was noted that 32/ 284 (11%) of patients who were classified as TBM by the Thwaites system were classified as "Non TBM" by the Lancet score and 6/258 (2%) of those who were diagnosed as possible, probable or definite TB were classified as Non TB by the Thwaites score. However, patients who had discordant results between these scores were not different from those who had concordant results when treatment was initiated based on expert clinical evaluation in the tertiary care setting.

Conclusion: There was only moderate agreement between the Thwaites' score and the Lancet consensus scoring systems. There is need to prospectively evaluate the cost effectiveness of simple but more effective rapid diagnostic alogrithm in the diagnosis of TB, particularly in a setting without CT and MRI facilities.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Meningitis; Scoring systems; Thwaites score; Lancet Consensus score; Agreement.

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis is one of the more serious manifestation of extra pulmonary TB constituting 6% of all TB cases.1 Among CNS tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis (TBM) remains the most common presentation. In spite of advances in diagnostic technology and effective therapeutic options, it continues to pose significant management challenges. Despite anti-TB chemotherapy, 20-50% of the affected people die and many who survive have significant neurological deficits. The case fatality is noted to be associated significantly with delay in diagnosis, treatment and HIV infection. The poor sensitivity of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture in diagnosis of pyogenic,2 and TBM is one of the major challenges in the diagnostic workup, hence many patients are treated empirically with antibiotics by care givers even before coming to a hospital leading to confusion with the entity "partially treated pyogenic meningitis".

Two commonly used methods -Thwaites' system,3 and more recently, the Lancet consensus scoring system have been developed to improve the diagnostic accuracy.4 The scoring systems include clinical features, CSF findings, as well as neurological imaging in making a diagnosis. Our medical unit diagnosis of TBM is made on a combination of clinical features and CSF findings (largely based on the Thwaites criteria), though finally decided by the treating consultant. CT and MRI tests were used only when there was suspected neurological defecit. We did not use any algorithm.

The present study evaluates the profile of patients with a diagnosis of CNS infections attending a tertiary care centre in India with a focus on TBM and compares the diagnosis made by the treating team with that of the Thwaites and the Lancet scoring systems.

Methods

Patients admitted under one medical unit of a tertiary level university teaching hospital with approximately 40,000 outpatients (OP) and 2000 inpatients (IP) per year were eligible for inclusion. The hospital has excellent medical records, and all information is stored electronically and coded according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 system of coding. The study data was collected for a period of 5 years (2006-2010) from IP charts of the medical unit. All patients who had readmission and did not have a diagnosis of CNS infection were included.

The search terms included pyogenic meningitis, tubercular meningitis, aseptic Meningitis and acute CNS infection. The data from the records was extracted into a clinical research form and entered into epidata version 3.4.11 for analysis. The extracted data was used to score all patients according to the Thwaites' scoring system and the Lancet scoring system for TBM. For all patients, adequate data was available from records to calculate both scores. All patients diagnosed as TBM were also scored using the medical research council (MRC), UK score.5

The Thwaites' Score has 5 parameters including age, the duration of illness, total white blood cell count, the CSF cell count and the percentage of CSF neutrophilia, with a maximum score of 13. If a patient has a total score of 4 or less, he/she is classified as tubercular meningitis and a score of more than 4 is suggestive of bacterial meningitis.2

The Lancet consensus scoring system has 20 parameters, which are devided in 4 categories (clinical, CSF, CNS imaging and evidence of TB elsewhere) with a maximum score of 20. A definite diagnosis of TBM is made if there is evidence of Acid Fast Bacilli (AFB) in CSF smear, culture or on histopathology of brain or spinal cord. A probable diagnosis is made if the total score is >10 pts if patients have no imaging, or >12 pts if imaging was used. A possible diagnosis is made with scores between 6-9 without imaging or 6-11 with imaging. Based on the total scores assigned, the diagnosis of TBM is either definite, probable, possible or no TBM.3 The clinical outcomes at discharge from the hospital were evaluated based on the Modified Rankin Score (MRS).6

Data analysis of continuous variables was described using means with standard deviations and categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Association between categorical variables was assessed using Chi-square test and comparison of means was done using independent two sample t-test. Patients with an MRS between 0-2 were catigorized as good outcomes and the 3-6 as poor outcomes. We evaluated whether there was any difference in outcomes based on the three scoring methods (i.e., the medical units’ diagnosis, the Thwaites score and the Lancet score). The differences in the discordant results between systems were analyzed using chi-square statistics. Epidata 3.4.11 was used for entry and all statistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 16, SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The study was approved by the institution of research board, study No: IRB (EC) - ER-4-24-08-2011.

Results

During the 5 year study period (2006-2010), 9892 patients were admitted under the medical unit. Of these, 338 IP records were identified using the search strategy as having CNS infections. Among these, 32 were either readmissions or were not CNS infections and were excluded based on inclusion/exclusion criteria, leaving 306 cases with a diagnosis of CNS infection, which were included in the analysis. As expected, only 29 of 234 (11%) cases for which mycobacterial cultures were sent grew had M. tuberculosis, all of whom were diagnosed as TB by all 3 methods.

Among the 306 patients, the final diagnosis of the treating physician was TBM in 84.6% (260/306), acute CNS infections in 9.5% (29/306), pyogenic meningitis in 4.2% (13/306) and aseptic meningitis in 1.3% (4/306). The age varied from 15 to 83 years with a mean of 37.3 (SD: 16.2). There were 192 (62.7%) males and 114 (37.3%) females. Of these, 11.8% (36/306) died and 33.3% (102/306) had significant residual neurological problems at discharge as evidenced by an MRS of 3-6.

Among these 306 patients, 284 (92.8%) were classified as "TBM" by the Thwaites’ score and the rest as "Pyogenic". While the Lancet classified 29 cases (9.5%) as "Definite-TBM", 43 cases (14.1%) as "Probable-TBM", 186 cases (60.8%) as "Possible-TBM" and 48 cases (15.7%) as "Non TBM".

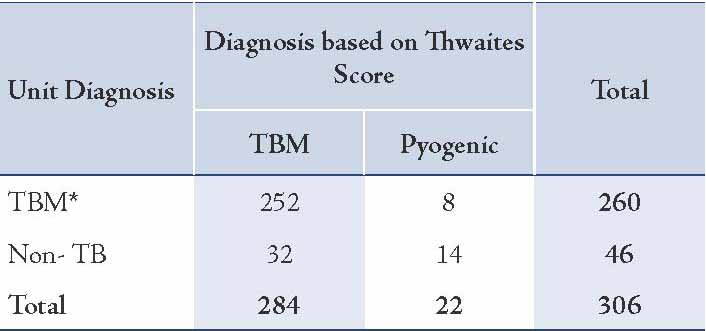

Table 1 compares the unit’s clinical diagnosis with the classification of the same patients by the Thwaites’ score. There was moderate agreement between the unit diagnosis and Thwaites classification (kappa 0.53). It was noted that 32/284 (11.3%) cases classified as "TBM" by Thwaites’ score were not diagnosed as "TBM" by the unit and 8/260 (3%) patients diagnosed as TBM by the Unit were not classified as TBM by the Thwaites score.

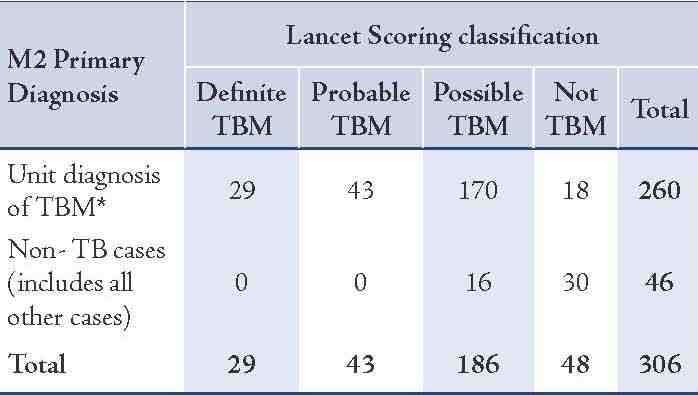

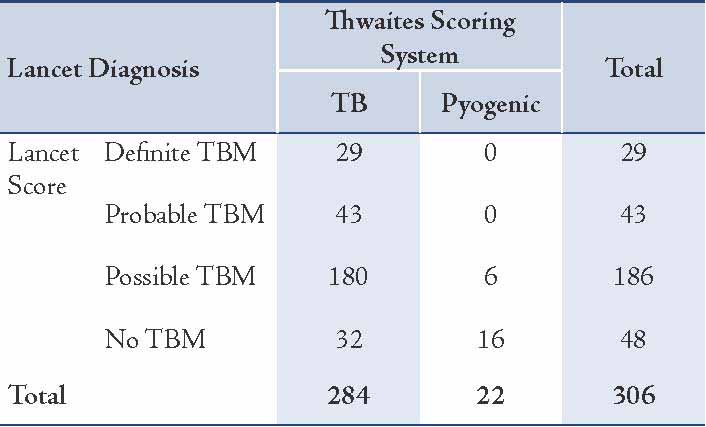

A comparison of the unit’s clinical diagnosis with the classification of the same patients by the Lancet score is seen in Table 2. Only a moderate agreement was observed between the two methods in diagnosing TBM. Namely only 17 /186 (9%) cases diagnosed as "Non TBM" by the unit were classified as "Possible TBM" by the Lancet score, and 18/260 (7%) cases diagnosed as "TBM" by the unit were classified as "Non TBM" by the Lancet score. The comparison of the two scoring systems is given in Table 3, which indicates that there is reasonably good agreement between the scores. It was also noted that 32/ 284 (11%) patients who were classified as TBM by the Thwaites' system were classified as "Non TBM" by the Lancet score and 6/258 (2%) of those who were diagnosed as possible, probable or definite TB were classified as Non TB by Thwaites' score. All of the six patients were under possible TB category.

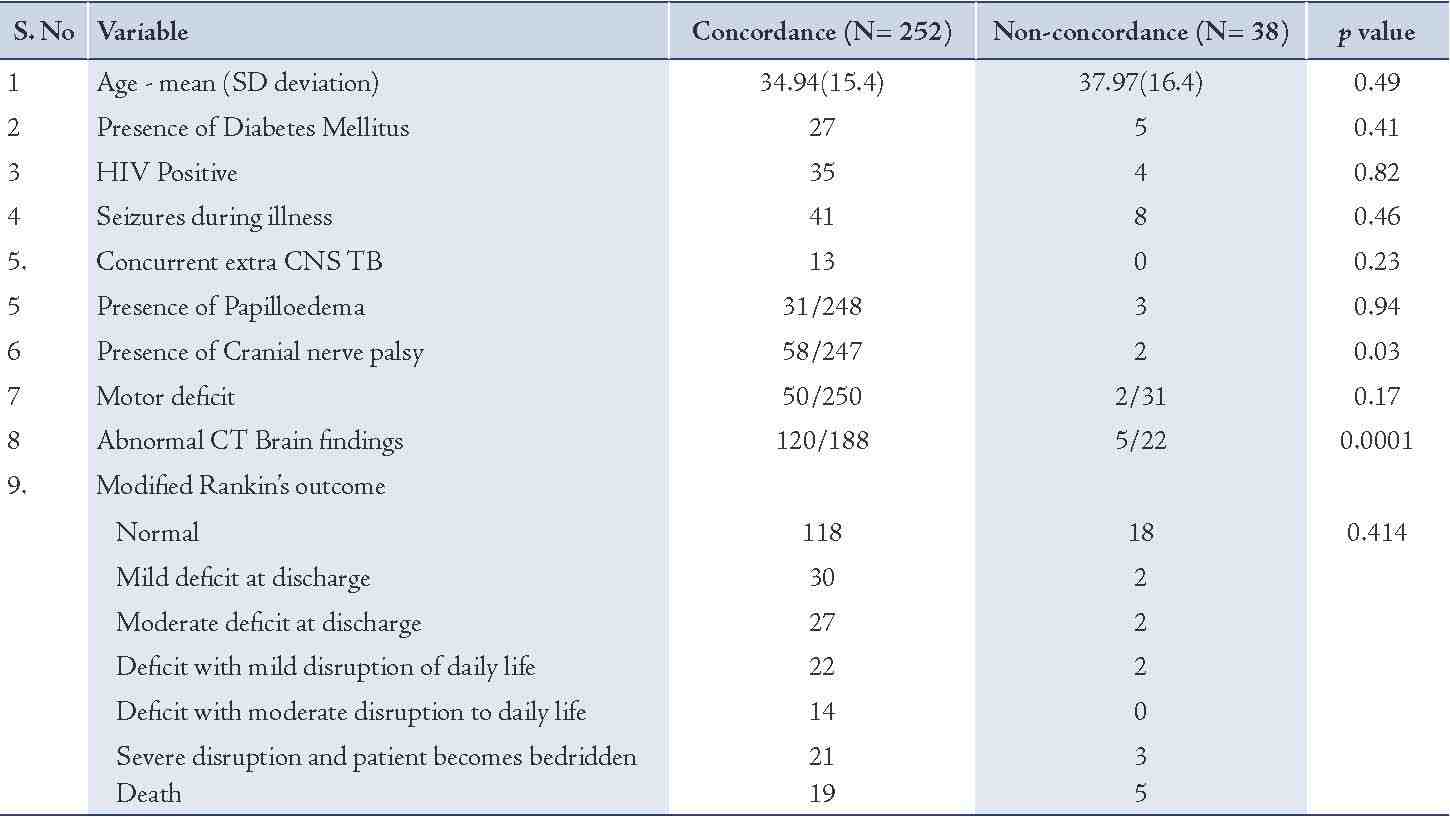

Table 4 highlights the reasons for the difference in classification. The results of the cranial nerve palsy and abnormal CT scan results contribute towards the difference between the scores. Some variables such as the presence of TB elsewhere appear more in those with concordant results, but do not pose any statistical significance.

Table 1: Comparison of the Medical unit’s diagnosis vs. the Thwaites score classification.

Table 2: Comparison of the Medical unit’s diagnosis vs. the Lancet score classification.

Table 3: Comparison of the Thwaites score vs. the Lancet score classification for the patients.

Table 4: Comparison of the patients’ characteristics in those with concordance and discordance of the Thwaites and Lancet consensus scores.

Discussion

This study describes a large cohort of patients with CNS infections in a tertiary care centre in South India, over a 5 year period. These constitute approximately 3% of all inpatient admissions in a medical ward. Among the cohort, 84% were TBM, mostly young men. The overall outcomes were classified as "Poor" in more than a third of patients. In the medical unit all patients with suspected or confirmed TBM were treated for 9 months to 1 year with anti TB therapy, 2 months of daily intensive therapy with INH, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide and Ethambutol, followed by a continuation phase of INH and Rifampicin. Steroids were given, with intravenous dexamethasone for the first 1-2 weeks, followed by a tapering schedule of prednisolone.7

It was noted that there was a moderate agreement between the medical unit’s diagnosis and the two scoring systems. The units’ diagnosis was however, based largely on the clinical features and CSF findings used in the Thwaites' score, and when there was neurological defecity the CT scan results were used as well. The Lancet score with CNS imaging criteria in addition to clinical criteria of cranial nerve palsies seemed to rule out many cases that would have been treated as TBM based on the Thwaites' score alone. Cranial nerve palsies in these patients had also been reported to have a poor outcome.8 The clinical outcome measure as described by the modified Rankin score was no different for the patients who had concordance between the scores and those who did not. Another study from India has found age greater than 40 and a high CSF protein concentration to predict mortality in TBM patients.9

While it is evident that neuro-imaging has significantly contributed to understanding the pathology and improved outcome in complicated CNS conditions. In developing countries like India, TBM will continue to be managed in the near future in canters without CNS imaging facilities due to poor access or availability. It is however, heartening to note that there was no significant difference in the clinical outcome based on categorization with and without CNS imaging in the tertiary care setting. Given the lack of a gold standard, clinicians will have to continue to use their clinical judgment based on clinical examination, scoring systems, and CSF examinations, as well as imaging studies where available to make the diagnosis and initiate prompt treatment. It is evident that diagnostic criteria are still imperfect and better tools are needed for the diagnosis of TBM. A study showed that half the patients with TBM had MRI Brain findings suggestive of vascular involvement.10

The following limitations of the study need to be highlighted. The scores were done on patients who had a final diagnosis of CNS infections and so their sensitivity and specificity may be higher than if done on patients with suspected CNS disease. Also, follow-up data was not available which would have been invaluable to compare the validity of different scoring systems more optimally. The lack of CSF serology and virology data on all studied patients limited our ability to assess how many could have been partially treated as pyogenic meningitis or viral infections.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the widely used Thwaites' score compares well with the more detailed and resource intensive Lancet consensus score. We also found that outcomes for patients who had discordant results between these scores were not different from those who had concordant results when treatment was initiated based on expert clinical evaluation in a tertiary care setting. However, prospective evaluation of cost-effectiveness of simple but more effective and rapid diagnostic tests are needed in the primary care setting where imaging facilities are lacking.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the microbiology department for their untiring work and 24 hour service for the diagnosis of TBM. Medical records department of the Christian Medical College for their diligent work that makes such studies possible. No conflicts of interest to disclose and no funding was received for this work.

References

1. CDC. reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2004. Atlanta, GA. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. September 2005. Available from. http://www.cdc.gov/TB/statistics/reports/surv2005/PDF/TBSurvFULLReport.pdf

2. Ahmed R, Thomas V, Qasim S; Thomas V; Qasim S. Cerebro spinal fluid analysis in childhood bacterial meningitis. Oman Med J 2008 Jan;23(1):32-33.

3. Thwaites GE, Chau TT, Stepniewska K, Phu NH, Chuong LV, Sinh DX, et al. Diagnosis of adult tuberculous meningitis by use of clinical and laboratory features. Lancet 2002 Oct;360(9342):1287-1292.

4. Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, Török ME, Misra UK, Prasad K, et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 2010 Nov;10(11):803-812.

5. Kennedy DH, Fallon RJ. Tuberculous meningitis. JAMA 1979 Jan;241(3):264-268.

6. van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988 May;19(5):604-607.

7. Török ME, Nguyen DB, Tran TH, Nguyen TB, Thwaites GE, Hoang TQ, et al. Dexamethasone and long-term outcome of tuberculous meningitis in Vietnamese adults and adolescents. PLoS One 2011;6(12):e27821.

8. Pehlivanoglu F, Yasar KK, Sengoz G. Prognostic factors of neurological sequel in adult patients with tuberculous meningitis. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2010 Oct;15(4):262-267.

9. George EL, Iype T, Cherian A, Chandy S, Kumar A, Balakrishnan A, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with meningeal tuberculosis. Neurol India 2012 Jan-Feb;60(1):18-22.

10. Kalita J, Prasad S, Maurya PK, Kumar S, Misra UK. MR angiography in tuberculous meningitis. Acta Radiol 2012 Apr;53(3):324-329.

|