Lymphomas are neoplasms arising from lymphoid tissues, diagnosed by biopsy as either Hodgkin or Non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The vast majority are of B-cell origin.1 They present either as a primary lesion or part of a malignant process. One-third of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are extranodal.2 The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is the most common site among all extranodal diseases.3 The most frequent GIT location is the cecum (35.7%), followed by the ileum (20.3%) and the rectum (9.1%).4 There is a male predominance, with the highest reported incidence in the 50–70-year age group.5

In 1961, Dawson et al,6 established the following criteria to diagnose primary colorectal lymphomas: no palpable superficial lymph nodes at presentation, no enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes on chest X-ray; white blood cell count (both total and differential) in the normal range; at surgery, only the regional lymph nodes are involved; and the liver and spleen are disease free.

The optimal approach is yet to be established in treating GIT lymphomas. The surgical option is still controversial.

In this paper, we report a case of an elderly Omani woman presented to our institution with altering bowel habits and weight loss, which was diagnosed later as stage IV primary rectal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. She was treated with chemotherapeutic agents.

Case Report

The patient was a 71-year-old woman with hepatitis B, hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia, and osteoporosis, and was on medications for these comorbidities. She presented to the Armed Forces Hospital, Muscat, with altering bowel habits of seven months duration, weight loss of 10 kg over the same period, vague epigastric pain, and on/off fatiguability. No fresh rectal bleeding or melena was reported.

Upon examination, the patient looked emaciated, pale, and dehydrated. Abdominal examination revealed a soft non-tender abdomen with bilateral enlarged inguinal lymph nodes; the left side was evident for two enlarged nodes 2 × 1 cm, discrete with no overlying skin changes. The right side showed one enlarged inguinal lymph node of 3 × 5 cm in size, rubbery, mobile, and non-tender with no skin changes.

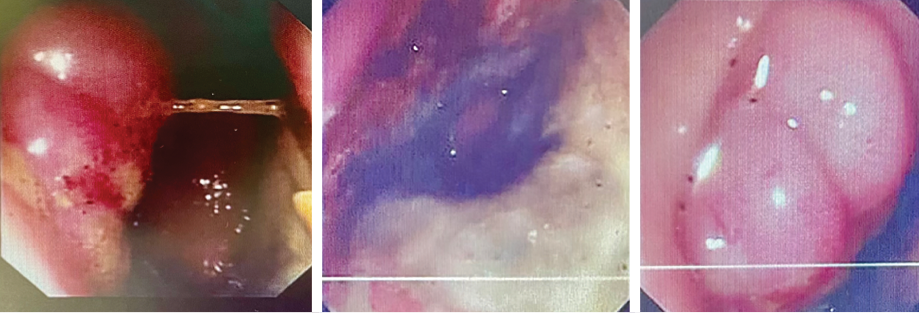

Rectal examination revealed perianal swelling with an ulcer [Figure 1]. There was circumferential hard mass up to 5–6 cm from the anal margin. Flexible sigmoidoscopy showed indurated circumferential lesion 5 cm from the anal margin, a biopsy of which was taken.

Figure 1: Endoscopic pictures of the tumor at the lower rectum.

Figure 1: Endoscopic pictures of the tumor at the lower rectum.

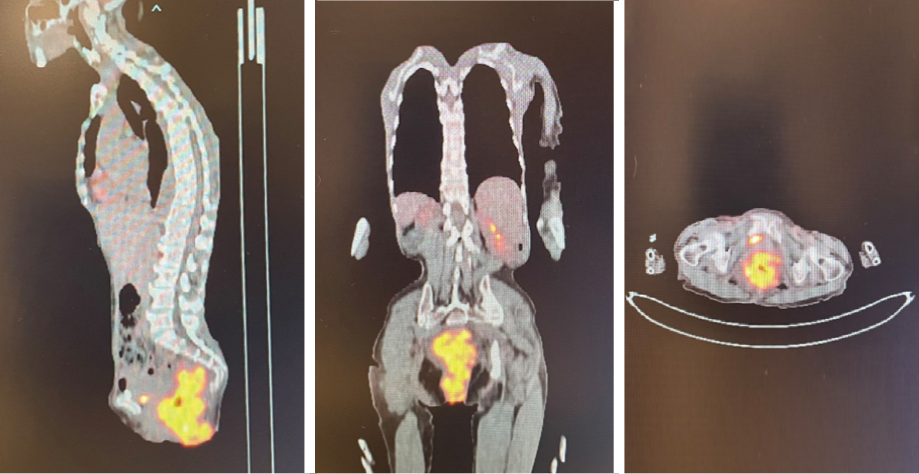

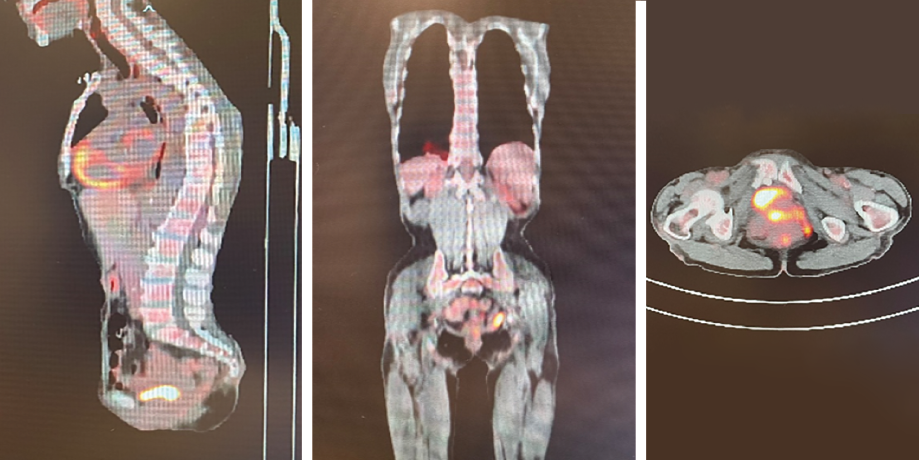

The patient was transferred to the oncology center at the nearby Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, where a computed tomography (CT) scan reported a circumferential asymmetrical enhancing thickening of the rectum, extending inferiorly involving the anal canal with mild perirectal inflammatory changes. Positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan results are shown in Figure 2. Even though magnetic resonance imaging was also planned, it could not be conducted as the patient was not cooperative.

Figure 2: Initial positron emission computed tomography images.

Figure 2: Initial positron emission computed tomography images.

Other than hypochromic microcytic anemia—for which the patient did not require a blood transfusion, having hemoglobin of 10–11 g/dL—laboratory investigations such as tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, alpha-fetoprotein) were within the normal ranges. Lactate dehydrogenase level, done prior to diagnosis, was high at 315 U/L.

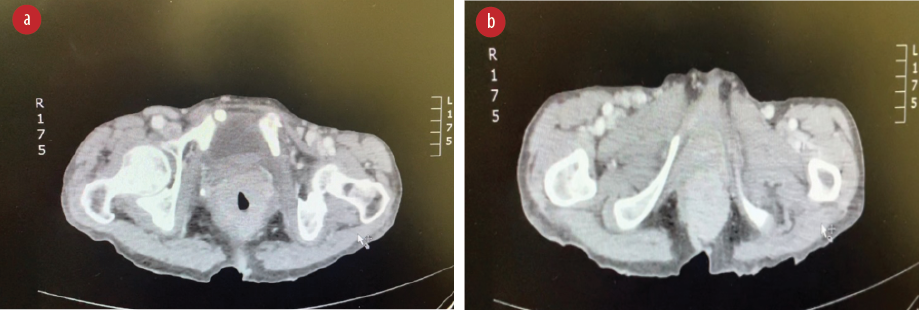

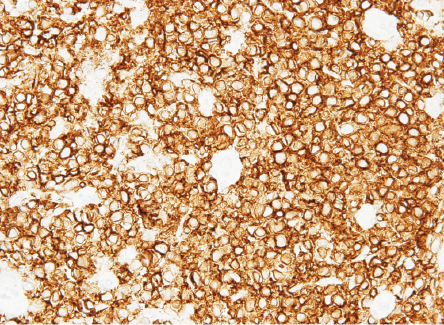

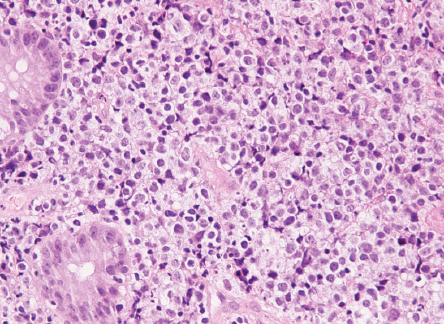

Biopsy revealed ulcerated rectal mucosa with underlying atypical lymphoid infiltrate composed of diffuse sheets of large, atypical cells with vesicular nuclei, multiple prominent nucleoli, and clear cytoplasm. The background showed abundant vasculature mixed with occasional small lymphocytes and neutrophils. There was no evidence of epithelial dysplasia. Immunohistochemistry results showed the neoplastic lymphoid cells positive for biomarkers CD20, BCL2, BCL6, and MUM1; and negative for CD3, CD10, CD5, CD30, AE1/AE3, chromogranin, and synaptophysin. Epstein-Bar virus-encoded RNA in situ hybridization was negative, and Ki-67 nuclear protein level was high at ≈ 50%. The final impression was that of high-grade lymphoma consistent with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, non-germinal center (activated B-cell) type [Figures 3–5].

Figure 3: (a) Extension of the tumor to the anal canal. (b) CT abdomen with contrast, showing thickening of the lower rectum.

Figure 3: (a) Extension of the tumor to the anal canal. (b) CT abdomen with contrast, showing thickening of the lower rectum.

Figure 4: B-lymphocyte CD20 marker seen diffusely positive in lymphoma cells.

Figure 4: B-lymphocyte CD20 marker seen diffusely positive in lymphoma cells.

Figure 5: Lymphoma cells infiltrating the lamina propria between the normal colonic crypts.

Figure 5: Lymphoma cells infiltrating the lamina propria between the normal colonic crypts.

The patient had pre-chemotherapy investigations such as complete blood count, urea, electrolytes, coagulation profile, cerebrospinal fluid study (no abnormal large lymphocytes found), bone profile, liver function test, thyroid function test, magnesium, C-reactive protein, hepatitis B polymerase chain reaction, and an intimal PET CT scan. Based on their findings, the patient was administered chemotherapy: six cycles of R-CHOP every three weeks. R-CHOP components were rituximab injection 500 mg/50 mL, cyclophosphamide injection 500 mg/vial, hydroxydaunorubicin hydrochloride (doxorubicin hydrochloride injection 50 mg/25 mL vial), vincristine injection 1 mg/vial (oncovin), prednisone 20 mg tablet, and intrathecal methotrexate 50 mg/5 mL: four cycles in total. As no malignant cells were found in cerebrospinal fluid, intrathecal methotrexate was given prophylactically. Marrow support was established by injecting filgrastim 300 μg/0.5 mL, a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

Complications of chemotherapy were mainly nausea and vomiting in which aprepitant capsules 125 mg were given as preventive, and granisetron injection 1 mg/mL to terminate an episode. The patient had a second PET scan performed before starting the fifth cycle of R-CHOP, which, in comparison to the first scan [Figure 2], showed persistent mild fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the rectum at the site of the previous soft tissue lesion, which was suggestive of complete metabolic response [Figure 6].

Figure 6: Positron emission computed tomography images at the end of treatment.

Figure 6: Positron emission computed tomography images at the end of treatment.

A subsequent colonoscopy showed the rectum as having a circumferential wall stricture at 5 cm from the anal verge; the stricture was dilated using a 15 mm balloon during the procedure. The sigmoid, descending, and transverse colon had normal mucosa with no inflammatory changes. Post-treatment, the patient responded reasonably well, was clinically stable, had no palpable lymph nodes, and physical examination was overall normal.

A repeat colonoscopy to evaluate the end-of-treatment response revealed a circumferential wall stricture at 5 cm from anal verge at the rectum, passed by oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy. Multiple biopsies were taken from the stricture site including a polyp. The stricture was dilated with a 15 mm balloon, and the biopsy showed chronic inflammation with focal mucosal fibrosis, likely secondary to treatment. No residual lymphomatous infiltrate was detected in this material. The patient was discharged on the same day with a follow-up PET scan scheduled for one month post-treatment. At one month follow-up, she was clinically improving.

Discussion

Several classifications are established for the diagnosis of lymphoma.7 Rectal lymphoma is the rarest reported rectal malignancy and presents with signs and symptoms indistinguishable from those of rectal carcinoma.8 The patients usually seek medical advice due to alterations in bowel habits, weight loss, or rectal bleeding. Our patient’s presentation had unspecific symptoms along with a rectal mass.

The diagnostic approach in such cases starts with a physical examination and a digital rectal examination, followed by a colonoscopy and biopsy for histopathological assessment and confirmation. Our patient’s histopathological examination revealed high-grade diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. After confirming a diagnosis, staging has to be conducted by a PET CT.

An ideal management approach for rectal lymphoma is yet to be established. Surgical intervention is mostly indicated for localized tumors, and many prefer medical treatment as the primary approach.9 Surgical management along with chemotherapy and radiotherapy has offered better outcomes than medical management alone in primary rectal lymphoma. However, secondary involvement of the rectum offers a poor prognosis and is considered better managed with radiation alone.10

Conclusion

One of the important aims of our case report is to demonstrate the significance of histopathological confirmation for a diagnosis, as seldom cases come across and the ideal management would largely relay on the correct diagnosis and proper staging of the disease. Even in advanced cases such as ours (stage IV), by means of surgical intervention and chemotherapy, a favourable outcome can be achieved.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s son.

references

- 1. Ralston SH, Penman ID, Strachan MW, Hobson R, editors. Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine. 23rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2018.

- 2. Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer 1972 Jan;29(1):252-260.

- 3. Herrmann R, Panahon AM, Barcos MP, Walsh D, Stutzman L. Gastrointestinal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer 1980 Jul;46(1):215-222.

- 4. Kohno S, Ohshima K, Yoneda S, Kodama T, Shirakusa T, Kikuchi M. Clinicopathological analysis of 143 primary malignant lymphomas in the small and large intestines based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology 2003 Aug;43(2):135-143.

- 5. Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis 2006 Sep;8(7):586-591.

- 6. Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg 1961 Jul;49(213):80-89.

- 7. Dodd GD. Lymphoma of the hollow abdominal viscera. Radiol Clin North Am 1990 Jul;28(4):771-783.

- 8. Kashimura A, Murakami T. Malignant lymphoma of large intestine –15-year experience and review of literature. Gastroenterol Jpn 1976;11(2):141-147.

- 9. Jinnai D, Iwasa Z, Watanuki T. Malignant lymphoma of the large intestine–operative results in Japan. Jpn J Surg 1983 Jul;13(4):331-336.

- 10. Devine RM, Beart RW Jr, Wolff BG. Malignant lymphoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 1986 Dec;29(12):821-824.