Multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disease of the central nervous system, is a debilitating and chronic condition with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 35.9 per 100 000 population.1 In Iran, the prevalence and incidence of MS are reported to range from 5.3–89/100 000 and 7–148.1/100 000, respectively.2 Recently, Gil-González et al,3,4 pointed out the importance of sociodemographic variables in addition to clinical variables as predictors of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and mental health in MS patients in Europe. A study in Oman found that understanding the HRQoL status of MS patients enabled better management of the disease.5 In addition to the physical problems of MS, its presence in a family member, especially one’s spouse, can trigger psychological trauma in the family. However, there is a dearth of research regarding couple and family support for MS patients.

Because MS tends to manifest itself in young people, often at the threshold of married life, it can impact the couple’s QoL.6,7 Therefore, the role of spouses in giving care to MS patients is vital, considering the possibility that it may gradually turn burdensome.8,9 The chronic burden on the caregiver spouse, who has to balance between income generation, childcare, and household chores, may trigger conflicts within the family, reduction in social support, family members feeling socially isolated, decreased care for the patient, and eventually, abandonment of the MS inflicted spouse.10

Marital life begins and develops based on the mutual relationship between the couples. In the long term, much depends on each partner’s psychological status and capacity for mutual adjustment. If one of them becomes an MS patient, their resilience to stress and marital commitment are put to severe long-term challenge, which can be especially difficult for the MS-afflicted spouse.6 Researchers working on MS-inflicted families have generally addressed the concept of family functioning in terms of how spouses and children relate to each other, make decisions, and help solve each other’s problems.11–14

A 2004 study that analyzed the HRQoL in MS patients found that the disease was associated with a high adverse impact on marital relationships and employment status.15 Divorce rates went up by more than a third in cases of primary progressive (PP) MS and nearly a quarter in progressive relapsing (PR) MS cases. Unemployment rates post-diagnosis rose by 71.3% and 65.8% in PP and PR MS patients, respectively.

Social support, especially as provided by MS patients’ spouses, needs to be put in perspective during treatment programs. Despite numerous psychological studies on MS patients around the world, rigorous studies with the host-parasite approach—covering biological, mental, social-cultural, spiritual, and moral aspects—on MS patients’ families are limited. Among all components of the host-parasite approach, restraints on investigating social, spiritual, and moral structures are more pronounced despite the fact that these variables have shown considerable influences in various chronic diseases. Studies within the host-parasite approach to chronic diseases indicated that similar to diabetes, MS leaves a sizable impact on the sexual relationships of married couples. This sets apart MS and diabetes from other chronic diseases as both disrupt the biological and psychological states of patients and their spouses. This highlights the higher burden on caregiver spouses of MS patients, leading to adverse psychological impacts on both the patient and the caregiver. In fact, with its typical progressing and relapsing nature, MS chronically affects family functioning and marital relationships.

Researchers in the field have been trying to delve into the factors affecting overall family functioning among patients with MS.16 The possible influences exerted by social support,17 spirituality,6 and ethics13 fall within this research avenue. Social support is an important social indicator and serves as one of the most fundamental factors affecting family functioning among patients with debilitating chronic diseases such as MS and their families. It can both help alleviate stressful life events and increase coping performance.18,19

Spirituality is another factor that influences family functioning and has cultural foundations. While many studies have been conducted on the possible relationships between spirituality and chronic diseases,20–22 there are few on the role of spirituality in the marital life of MS patients. Generally, these studies suggest that individuals with spiritual orientations can better cope with harmful and stressful situations, handle pressure, and achieve better health status. Moreover, spiritual tendencies improve the psychological well-being and mental health. Expanding literature on MS support not only deficits in executive and socio-emotional domains but also low levels of permissibility of immoral actions and emotional detachment in the moral judgment process.23

An issue of concern is the reaction of MS patients’ spouses and the way they deal with the problem. In some cases, couples continue with their marital life despite having a chronic disease even to the point that their relationship may become deeper after diagnosis, which in turn, may lead to a better outcome.16 On the contrary, in some cases couples break up and end their marital life, which leads to exacerbation of conditions in the MS-afflicted partner.24,25 Research reports and psychology guidelines on MS patients have been mainly concerned with ‘caretakers’, which implies tending along more physical lines. In contrast, ‘support’ as conceptualized in our study goes well beyond mere physical caregiving and encompasses psychological and emotional backups. Many MS patients might have somebody around to help them with their everyday life routines. However, patients might be deprived of more intimate psychological/emotional support, a missing link in the research on MS patients, which our study has aimed to address. Namvar found that interpersonal dependence and the challenges of emotion regulation play a vital role in family functioning among MS patients’ spouses.25 The missing influence from meaning and morality needs to be addressed to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the family functioning in MS-inflicted couples. Therefore, the primary objective of the present study was to determine the contribution of social support from family, friends, and others in predicting the family functioning of MS patients’ spouses, taking into account the mediating role of spiritual experiences and moral foundations.

Methods

The conceptual model of the variables of the study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Conceptual model of family functioning of married patients with multiple sclerosis. These variables show the hypothesis of the current study.

Figure 1: Conceptual model of family functioning of married patients with multiple sclerosis. These variables show the hypothesis of the current study.

A descriptive and correlational research method was employed following the path analysis methodology. Namvar method was used to ascertain the population statistics, which comprised all spouses of MS patients who were selected based on judgmental and voluntary sampling using the Kline formula.25,26 The target group was designated by consulting support centers and associations for patients with MS in Tehran. The designed questionnaires were distributed among spouses of MS patients referring to the centers and associations for MS patients, who participated voluntarily to achieve optimal outcomes. Inclusion criteria were as follows: the participants were married, their spouses were diagnosed with MS by a neurologist, and received no psychological or psychiatric intervention over the past year.

Ethical requirements were observed in this research as all participants took part in the study voluntarily, their information was kept confidential, and the Declaration of Helsinki was observed in conducting the study. Ethical approval of the study was granted by the ethical committee at Islamic Azad University and Multiple Sclerosis Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran (Defense Date 1394.6.26).

The selected participants filled out the questionnaire booklets comprising four instruments: McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD), Social Support Appraisals Scale, Daily Spiritual Experience Scale, and Moral Foundations Questionnaire. Together, they collected data on family functioning, social support, spiritual experiences, and ethics.

FAD is a 60-item questionnaire designed by Epstein et al,27 based on the McMaster model to measure family functioning. The FAD instrument includes the following seven subscales (the validity coefficient of each is given parenthetically): problem-solving (0.68), communication (0.57), roles (0.63), affective responsiveness (0.67), affective involvement (0.77), behavior control (0.79), and general functioning (0.70).

Social Support Appraisals Scale, a 23-item questionnaire, was developed based on Cobb’s definition of social support.28 The instrument has an overall validity coefficient score of 0.91. In this scale, ‘social support’ refers to the extent to which an individual believes that he or she is loved by, esteemed by, and involved with, family (validity coefficient: 0.87), friends (0.80), and others (0.79).

Daily Spiritual Experience Scale is a 16-item instrument that assesses spiritual experiences of an individual.29 It probes the spiritual orientation of the respondent such as perceived connection with transcendent, experiencing feelings of awe, gratitude for blessings, mercy, deep inner peace, and giving and receiving compassionate love. The validity coefficient of this instrument is 0.91.

Moral Foundation Questionnaire is a 30-item instrument used to collect data on five dimensions of morality foundation.30 Graham et al,30 introduce these dimensions as fundamental moral bases among different ethical, racial, and lingual cultures and identities. The overall validity coefficient score of this instrument is 0.90. Its five subscales (with the individual validity coefficient of each) are as follows: care/harm (0.61), fairness/reciprocity (0.60), ingroup loyalty (0.66), respect of authority (0.57), and purity (0.71).

Results

Of the 300 questionnaire booklets returned to us, 80 were unusable being incomplete, blank, or with distorted responses. The remaining 220 booklets were used for the study. There were four categories of MS patients in the sample: PPMS, relapsing-remitting MS, secondary progressive MS, and PRMS [Table 1].

Table 2 presents the descriptive indicators and normal distribution of the scores from scales used in the study. Findings suggested that among predictor variables, only social support had a significant regression relationship with moral foundations and spiritual experiences [Table 3]. Nevertheless, the explained variances of these two variables were relatively weak at 4.5% and 12.6%, respectively. On the other hand, the variance of family functioning explained by social support was 28.3%. In addition, the variance of family functioning explained through moral foundations and spiritual experiences was very weak at 0.6%.

Table 1: Demographic details of the participants (N = 220) and their spouses.

|

Gender of the respondent

(spouse of the MS patient)

|

|

|

Female

|

35 (15.9)

|

|

Male

|

135 (61.4)

|

|

Not stated

|

50 (22.7)

|

|

Education of the respondent

|

|

|

Illiterate

|

5 (2.3)

|

|

Below high school

|

14 (5.0)

|

|

High school diploma

|

68 (30.9)

|

|

Occupational training

|

8 (3.6)

|

|

Undergraduate

|

40 (18.2)

|

|

Postgraduate

|

18 (8.2)

|

|

Doctorate

|

12 (5.5)

|

|

Not stated

|

55 (25.0)

|

|

Types of MS

|

|

|

Relapsing-remitting

|

12 (5.5)

|

|

Primary progressive

|

6 (2.7)

|

|

Progressive relapsing

|

8 (3.6)

|

|

Secondary progressive

|

6 (2.7)

|

MS: multiple sclerosis.

Table 2: Descriptive indicators and Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test of the collected data.

|

Overall family functioning

|

2.0 ± 0.4

|

0.20

|

0.21

|

0.69

|

|

Spiritual experiences

|

6.3 ± 0.9

|

-0.54

|

0.68

|

0.04

|

|

Moral foundations

|

3.2 ± 0.7

|

-0.22

|

-0.18

|

0.06

|

|

Family

|

2.0 ± 0.6

|

0.58

|

0.73

|

0.09

|

|

Friends

|

2.0 ± 0.4

|

0.52

|

1.76

|

0.12

|

|

Others

|

1.9 ± 0.4

|

0.23

|

2.34

|

0.13

|

Table 3: Stepwise regression relationship with moral foundations and spiritual experiences.

|

Social support

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moral foundations

|

0.045

|

-0.174*

|

-0.283

|

0.111

|

|

Spiritual experiences

|

0.126

|

-0.332**

|

-0.629

|

0.122

|

|

Family functioning

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social support

|

0.283

|

|

|

|

|

Family

|

|

-0.181**

|

-0.137

|

0.063

|

|

Friends

|

|

-0.142

|

-0.074

|

0.040

|

|

Others

|

|

-0.014

|

0.012

|

0.067

|

|

Overall

|

|

0.086

|

0.098

|

0.067

|

|

Moral foundations

|

0.081

|

0.056

|

0.049

|

*p < 0.050; **p < 0.010; R2: coefficient of determination; SE: standard error.

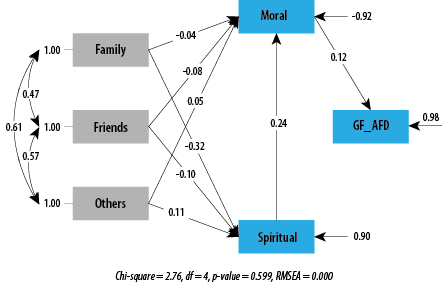

Another model was designed to examine the effect of social support subscales on family functioning. Here, the social support subscales were evaluated based on the modified subscale of the overall functioning. The results of the model designed for the overall functioning subscale are illustrated in Figure 2. As observed in this figure, indirect path coefficients of friends’ and others’ support were not statistically significant on the overall family functioning subscale through both mediating variables (root mean square error of approximation < 0.001).

Note: Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was < 0.001, indicating that the approximate error of the model was less than the expected value.

Note: Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was < 0.001, indicating that the approximate error of the model was less than the expected value.

Figure 2: Diagram and standard path coefficient of the overall family functioning model.

The only significant relationship was between family support and overall family functioning through spiritual experiences. The relationship between mediating variables of spiritual experiences also had a significant effect on the overall functioning through moral foundations. After removing insignificant relationships and estimating fit indicators, the modified model indicated goodness of fit with data. The chi-square value (2.76) with a degree of freedom = 4 was statistically insignificant, showing a fit. The ratio of chi-square to degree of freedom equaled 0.69, which was consistent with the acceptance criteria.

Figure 2 shows a root mean square error of approximation < 0.001, goodness-of-fit index = 0.98, comparative fit index = 0.99, and normed fit index = 0.97, indicating goodness of data fit. Expected cross validation index equaled 0.079 and the value of this index for the saturated model was 0.087, which is in line with the criterion proposed by Eboli and Mazzulla.31 Moreover, the squared multiple correlation values equaled 0.15, indicating that almost 15% of the overall functioning subscale was explained based on the final model.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effect of the components of social support on the family functioning of MS patients in Iran, underpinned by the mediating role of spiritual experiences and moral foundations. Our results provide evidence for the benefits of family support for MS patients. The mediating role of spiritual experiences and moral foundations also became evident.

MS diagnosis in a husband or wife can potentially impair the whole family system mentally, emotionally, and socially due to chronic disruptions in the normal marital roles.32,33 For example, MS may prevent men from providing for their families. As in many other communities, Iranian women play the stabilizing role of carrying the collective emotional burden of the family, managing the relationships between its members, in addition to raising children, and managing household chores. Therefore, if the woman is afflicted by MS, she is prevented from fulfilling this major responsibility. Here, we must remember that the prevalence of MS in females is twice as in males.

Our results indicated that family support was vital for MS patients compared to the support from friends and others. The direct effect of social support on the family functioning of patients with chronic diseases has already been reported in many studies from various contexts.17–19 In fact, the supportive role of spouses—their very presence and sincere attitude without expecting anything in return—is deemed an important component of any treatment program for married MS patients.

In rare studies, MS has been reported to result in complications such as loss of self-esteem, feeling shame, and catastrophizing, leading to deeper psychophysiological dysfunction, isolation, and reduction in marital intimacy.34 On the other hand, other studies have found that spouses who had intimate relationships prior to MS diagnosis decided to strengthen their relationships and care for each other in the face of the crisis. Literature generally tends to confirm family support, particularly from the spouse.35–38 However, empirical evidence from Iran indicates that in married patients, MS may result in feelings of rejection, emotional isolation, and even divorce.35 A comprehensive approach to health psychology needs to consider cultural, social, and ethnic influences including the social status of the patient when treating chronic diseases such as MS. This is particularly evident in developing countries with traditional cultures, where these influences tend to be pronounced.

We found a significant relationship between social support and overall family functioning through spiritual experiences as a mediating variable. The positive role of spirituality in this study is consistent with the findings of studies on patients with heart diseases and cancer.21,39 A 2019 study introduced spirituality and spiritual well-being as the fourth dimension of health.40 Studies show that individuals with strong spiritual beliefs, who are in connection with stable spiritual sources can better endure and cope with marital problems.41,42 They also generally show less friction in their family relationships and in dealing with everyday problems. On the contrary, grown-up children of families with low sense of spirituality were reported to exhibit more instances of shirking from responsibility and keeping low profile during crises when family members need support.43 Living with a patient who suffers from a chronic illness might push some people to search for meaning in life and thereby embrace a degree of spirituality.

However, spirituality need not necessarily arise under any strong adverse circumstance. Rather, in some individuals a propensity for spirituality may develop early in life, perhaps as a result of the complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors, including being exposed to early adversities, triggering an inner search for the meaning of life.

The current study investigated whether morality (moral foundations) and spiritual experiences as mediating variables affected the family functioning of married MS patients in Iran. Our results indicated a significant impact of these. Our findings support the impact of spirituality and morality on endurance, ethical commitment, intimacy, and satisfaction in MS-inflicted families.

Previous studies examined the role of ethics and moral judgment in QoL as well as marital satisfaction and adjustment in families of patients with chronic diseases.6,11,43 A contribution of the present study is establishing the effective role of ethics, including care, loyalty, purity, fairness, and respect in the family functioning of MS patients. Morality is an important attribute in an evolved human being, which deeply underpins all concepts and meanings individuals have assumed in the course of their life. It gives meaning to the individual’s commitments and enables them to stoically and passionately care for their MS-inflicted spouses leading to better QoL and response to treatment.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the role of family support—particularly the support of the spouse—for Iranian MS patients as compared with support provided by friends and others in the community. Spiritual experiences were found to play a significant mediating role in family functioning through moral foundations. The presented model is recommended for enriching marital relationships and improving family functioning. Further research is recommended to shed more light on morality and spirituality, the two vital dimensions of human nature, and how it impacts families with MS patients. Our findings are believed to have the potential to be integrated into training packages for families of patients who suffer from chronic diseases such as MS. It is recommended to consider the pivotal role of family support in treatment programs for MS patients in developing as well as developed countries.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by Islamic Azad University, Saveh Branch.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants of this study. We also would like to convey our appreciation to Dr. Reza Ghorban Jahromi (Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran), Dr. Mohammad Reza Masrour (Islamic Azad University, Saveh Branch, Saveh, Iran), and Mrs. Fatemeh Salimi (Raftar Institute, Tehran, Iran) for their contributions to our study.

references

- 1. Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, Kaye W, Leray E, Marrie RA, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 2020 Dec;26(14):1816-1821.

- 2. Azami M, YektaKooshali MH, Shohani M, Khorshidi A, Mahmudi L. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019 Apr;14(4):e0214738.

- 3. Gil-González I, Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Conrad R, Martín-Rodríguez A. Predicting improvement of quality of life and mental health over 18-months in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021 Aug;53:103093.

- 4. Gil-González I, Martín-Rodríguez A, Conrad R, Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2020 Nov;10(11):e041249.

- 5. Natarajan J, Joseph MA, Al Asmi A, Matua GA, Al Khabouri J, Thanka AN, et al. Health-related quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis in Oman. Oman Med J 2021 Nov;36(6):e318.

- 6. Aghaei Y, Kalantar-Kousheh SM, Naeemi E, Naser MA. Phenomenology of effective psychological components on marital adjustment among married people suffering from multiple sclerosis. J Qual Res Health Sci 2020 Jul;7(2):144-156.

- 7. Srivastava S, Shekhar S, Bhatia MS, Dwivedi S. Quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease and panic disorder: a comparative study. Oman Med J 2017 Jan;32(1):20-26.

- 8. Milbury K, Badr H, Fossella F, Pisters KM, Carmack CL. Longitudinal associations between caregiver burden and patient and spouse distress in couples coping with lung cancer. Support Care Cancer 2013 Sep;21(9):2371-2379.

- 9. Al-Azri M, Al-Awisi H, Al-Rasbi S, El-Shafie K, Al-Hinai M, Al-Habsi H, et al. Psychosocial impact of breast cancer diagnosis among Omani women. Oman Med J 2014 Nov;29(6):437-444.

- 10. Hauer L, Perneczky J, Sellner J. A global view of comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review with a focus on regional differences, methodology, and clinical implications. J Neurol 2021 Nov;268(11):4066-4077.

- 11. Boeije HR, Van Doorne-Huiskes A. Fulfilling a sense of duty: how men and women giving care to spouses with multiple sclerosis interpret this role. Community Work Fam 2003 Dec;6(3):223-244.

- 12. Bužgová R, Kozáková R, Škutová M. Factors influencing health-related quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Eur Neurol 2020;83(4):380-388.

- 13. Realmuto S, Dodich A, Meli R, Canessa N, Ragonese P, Salemi G, et al. Moral cognition and multiple sclerosis: a neuropsychological study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2019 May;34(3):319-326.

- 14. Dahraei HA, Adlparvar E. The relationship between family functioning, achievement motivation and rational decision-making style in female high school students of Tehran, Iran. International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies 2016 Sep;3(2):456-463.

- 15. Morales-Gonzáles JM, Benito-León J, Rivera-Navarro J, Mitchell AJ, Group GS; GEDMA Study Group. A systematic approach to analyse health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the GEDMA study. Mult Scler 2004 Feb;10(1):47-54.

- 16. O’Hara JK, Canfield C, Aase K. Patient and family perspectives in resilient healthcare studies: a question of morality or logic? Saf Sci 2019 Dec;120:99-106.

- 17. Rommer PS, Sühnel A, König N, Zettl UK. Coping with multiple sclerosis-the role of social support. Acta Neurol Scand 2017 Jul;136(1):11-16.

- 18. ŞİMŞİR Z, Tolga S, Dilmaç B. Predictive relationship between adolescents’ spritual well-being and perceived social support: the role of values. Research on Education and Psychology 2018 Jun;2(1):37-46.

- 19. Zhong Y, Wang J, Nicholas S. Social support and depressive symptoms among family caregivers of older people with disabilities in four provinces of urban China: the mediating role of caregiver burden. BMC Geriatr 2020 Jan;20(1):3.

- 20. Lim HA, Tan JY, Chua J, Yoong RK, Lim SE, Kua EH, et al. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients in Singapore and globally. Singapore Med J 2017 May;58(5):258-261.

- 21. Røen I, Brenne A-T, Brunelli C, Stifoss-Hanssen H, Grande G, Solheim TS, et al. Spiritual quality of life in family carers of patients with advanced cancer-a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 2021 Sep;29(9):5329-5339.

- 22. Park SA, Park KW. The mediating effect of self-differentiation between college student’s family functioning and smart phone addiction. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 2017 Apr;18(4):325-333.

- 23. Hammond SR, McLeod JG, Macaskill P, English DR. Multiple sclerosis in Australia: socioeconomic factors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996 Sep;61(3):311-313.

- 24. Latorraca CO, Martimbianco AL, Pachito DV, Torloni MR, Pacheco RL, Pereira JG, et al. Palliative care interventions for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019 Oct;10(10):CD012936.

- 25. Namvar H. The relationship between marital satisfaction of patients with multiple sclerosis (the patients’ spouses) with the interpersonal dependency and personality type. Am J Fam Ther 2021 Aug:1-6.

- 26. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th ed. Guilford Publications; 2016.

- 27. Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster family assessment device. J Marital Fam Ther 1983 Apr;9(2):171-180.

- 28. Vaux A, Phillips J, Holly L, Thomson B, Williams D, Stewart D. The social support appraisals (SS-A) scale: studies of reliability and validity. Am J Community Psychol 1986 Apr;14(2):195.

- 29. Underwood LG, Teresi JA. The daily spiritual experience scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann Behav Med 2002;24(1):22-33.

- 30. Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Spassena K, Ditto PH. Moral foundations questionnaire (MFQ) [Database record]. APA PsycTests; 2011.

- 31. Eboli L, Mazzulla G. Structural equation modelling for analysing passengers’ perceptions about railway services. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2012 Oct;54:96-106.

- 32. Thomson A, Dobson R, Baker D, Giovannoni G. Digesting science: developing educational activities about multiple sclerosis, prevention and treatment to increase the confidence of affected families. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2021 Jan; 1;47:102624.

- 33. Di Tella M, Perutelli V, Miele G, Lavorgna L, Bonavita S, De Mercanti SF, et al. Family functioning and multiple sclerosis: study protocol of a multicentric Italian project. Front Psychol 2021 Jun;12:668010.

- 34. Juibari TA, Behrouz B, Attaie M, Farnia V, Golshani S, Moradi M, et al. Characteristics and correlates of psychiatric problems in wives of men with substance-related disorders, Kermanshah, Iran. Oman Med J 2018 Nov;33(6):512-519.

- 35. Tajikesmaeili A, Gilak HA. Sexual functions and marital adjustment married woman with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Research in Psychological Health 2016 Jul;10(2):1-9.

- 36. Maguire R, Maguire P. Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: recent trends and future directions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2020 May;20(7):18.

- 37. Alroughani R, Inshasi J, Al-Asmi A, Alkhabouri J, Alsaadi T, Alsalti A, et al. Disease-modifying drugs and family planning in people with multiple sclerosis: a consensus narrative review from the Gulf Region. Neurol Ther 2020 Dec;9(2):265-280.

- 38. Clark AA, Flamez B, Vela JC. Multiple sclerosis: moving beyond physical and neurological implications into family counseling. Appl Sci (Basel) 2020 Jan:22.

- 39. Zhang Z, Tumin D. Expected social support and recovery of functional status after heart surgery. Disabil Rehabil 2020 Apr;42(8):1167-1172.

- 40. Azizi F. Ethics and spirituality in medical sciences. Majallah-i Ghudad-i Darun/Riz va Mitabulism-i Iran 2019 Feb;20(5):209-211.

- 41. Azimian M, Arian M, Shojaei SF, Doostian Y, Ebrahimi Barmi B, Khanjani MS. The effectiveness of group hope therapy training on the quality of life and meaning of life in patients with multiple sclerosis and their family caregivers. Iran J Psychiatry 2021 Jul;16(3):260-270.

- 42. Kouzoupis AB, Paparrigopoulos T, Soldatos M, Papadimitriou GN. The family of the multiple sclerosis patient: a psychosocial perspective. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010;22(1):83-89.

- 43. Park J, Roh S. Daily spiritual experiences, social support, and depression among elderly Korean immigrants. Aging Ment Health 2013;17(1):102-108.