High quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) remains the most important determinant of cardiac arrest survival, as emphasized by the guidelines of various resuscitation associations.1–4 Patient showing signs of awareness without pulse during CPR is a rare and challenging phenomenon. CPR induced consciousness (CPRIC) is defined as a display of at least one of the following behaviors in pulseless patients undergoing active CPR: spontaneous eye opening, jaw tone, speech, or body movement.5 With the advancement in resuscitation science, the number of reported cases of CPRIC has increased.6–8 However, the pathophysiology of this condition remains poorly understood.5,6 CPRIC has multiple implications on the quality of care provided. It causes psychological effects on both the patients and the healthcare providers. We report a case of CPRIC to raise the awareness about this phenomenon and its implications. We will also discuss the proposed treatment options. This case was observed at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, in 2019.

Case Report

A 49-year-old male presented to the emergency department with retrosternal chest pain suggestive of myocardial ischemia. Three months previously, he had ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) for which he received thrombolytic therapy. His physical examination was unremarkable.

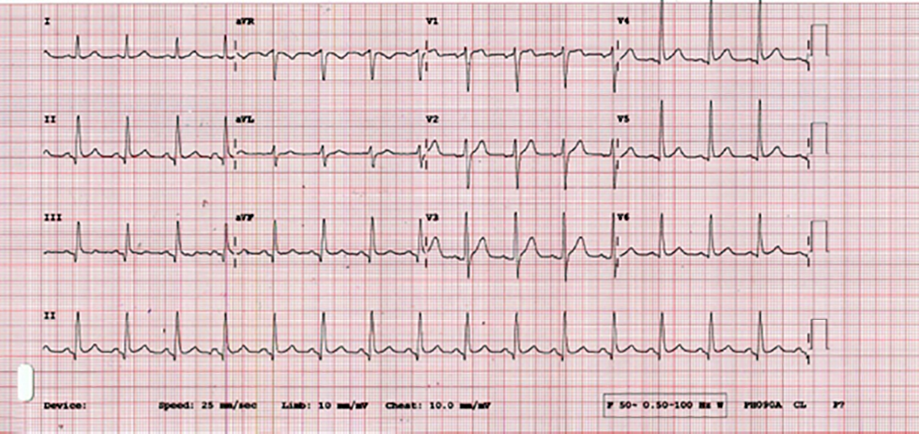

Figure 1: Patient’s ECG at the presentation.

Table 1: Medications used to restrain patients expressing cardiopulmonary resuscitation induced consciousness.11

|

Administer ketamine bolus, mg/kg |

|

|

IV |

0.5–1.0 |

|

IM |

2.0–3.0 |

|

Consider co-administration of midazolam bolus, mg |

|

|

IV |

1.0 |

|

If continuous sedation is needed: |

|

|

Repeat ketamine bolus after 5–10 min, mg/kg |

|

IV |

0.5–1.0 |

|

IM |

2.0–3.0 |

|

Start ketamine infusion, μg/kg/min |

|

IV: intravascular; IM: intramuscular.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) performed shortly after presentation revealed pathological q-waves at the inferior leads [Figure 1]. While being assessed, the patient became unresponsive, taking labored, agonal breaths. The cardiac monitor displayed ventricular fibrillations (VF). CPR was initiated, and 200 J electrical defibrillation delivered. Two minutes later, a sustained heart rhythm of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved, and the vital signs were within normal limits. A repeat ECG yielded results similar to the initial one. Bedside echocardiogram revealed akinetic anterior wall, with the apex suggestive of the previous myocardial infarction. Ten minutes later, he again became unresponsive and developed VF. CPR was recommenced and defibrillation performed. During the CPR, the patient started moving, pulling the hands away from his chest, kicking foot, and verbalizing. Assuming that he had attained ROSC, the team halted the CPR. However, the cardiac monitor displayed VF and the patient had no palpable pulse. Resuscitation was immediately resumed as per the Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) guidelines. During the subsequent cycles of CPR, the patient had more episodes of environmental awareness and consciousness which required physical restraint. The patient was then sedated with midazolam 0.1 mg/kg and administered Succinylcholine 1.5 mg/kg for endotracheal intubation. He achieved ROSC several times for short intervals (< 1–2 minutes each) before relapsing. The cardiac arrest rhythms alternated between VF and pulseless electrical activity. He received a total of 23 electrical defibrillations, two doses of amiodarone (300 mg and 150 mg), lidocaine 120 mg, and epinephrine 1 mg every 3 minutes. The patient was actively resuscitated for 2.5 hours. Despite all attempts, his cardiac rhythm deteriorated to asystole, and he was declared dead.

The resuscitation team were overwhelmed by the fact that the patient had repeatedly shown signs of revival without spontaneous cardiac activity. Most team members were unaware of the CPRIC phenomenon, and they required extensive debriefing to understand the concept and decrease any psychological impact on them.

Discussion

CPRIC is a newly observed phenomenon with very few reported cases. An observational study in 16 558 out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients identified only 112 (0.7%) CPRIC cases.5 CPRIC was more likely in patients who had early CPR and defibrillation. It was also more common in young male patients who had ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia.5

The occurrence of CPRIC can affect the performance of the resuscitation team, as they may confuse CPRIC with ROSC. They may engage in frequent inappropriate rhythm and pulse checks, resulting in too many CPR interruptions. Several studies have demonstrated that CPRIC increases interruption time and decreases the quality of CPR in all aspects.6,9–11 A systematic review revealed that in half of the reported cases, the patients were able to push the rescuers away, causing breaks in the CPR process and premature removal of the endotracheal tube.6

A CPRIC event can also affect the resuscitation team psychologically. A recent survey reported detrimental psychological impact on 90% of the resuscitating team members.9 About 52% of the physicians felt uncomfortable during resuscitation and 7% experienced insomnia, nightmares, and mood changes that lasted for weeks.9

Survivors of cardiac arrest are at risk of developing short- and long-term psychological sequalae. Previous studies reported 10%–20% of cardiac arrest survivors as being able to recall specific details of their resuscitation from the time of the cardiac arrest.12–15 On the other hand, 2% of the cardiac arrest survivors were alert during the discussions among the resuscitating team members.12 The patients who recall their resuscitation details may be at increased risk of short and long term psychological sequelae.5 In a study among 101 patients who survived cardiac arrest, 46% recalled the events after the cardiac arrest tinged with overarching themes related to fear, animals, plants, bright light, violence, déjà vu, and family.12

Despite CPRIC’s impact on the resuscitating team and the patients’ outcome, there are no available controlled trials addressing this phenomenon. We used midazolam to control the patient agitation during CPRIC. Two guidelines were published about the management of CPRIC based on expert consensus: the Dutch National Ambulance Guidelines and the State of Nebraska Model Protocol [Table 1].5,15 Both the guidelines were used for the pre-hospital setting. The Dutch guideline recommends fentanyl and midazolam while the State of Nebraska protocol recommends using ketamine and midazolam.

conclusion

Occurrence of CPRIC can have a significant impact on the successful resuscitation of cardiac arrest victims. The resuscitation team should administer sedating agents and continue to provide high-quality CPR and minimize interruptions. Debriefing the CPR team is important to minimize the psychological impact and improve the team’s performance. Further studies are needed to address the consequences of CPRIC among health care providers and establish solid guidelines in managing it.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Informed consent was not possible to obtain as the patient died in the emergency department and has no identifiable next of kin. However, consent was signed by the sponsor of the patient.

references

- 1. Meaney PA, Bobrow BJ, Mancini ME, Christenson J, de Caen AR, Bhanji F, et al; CPR Quality Summit Investigators, the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee, and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: [corrected] improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013 Jul;128(4):417-435.

- 2. Travers AH, Rea TD, Bentley BJ, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Sayre MR, et al. Part 4: CPR overview. 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2010 Nov 2;122(18 suppl 3):S676-S684.

- 3. Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support. . 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2010 Nov 2;122(18 suppl 3):S729-S767.

- 4. Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Samson RA, Hazinski MF, Atkins DL, et al. Part 14: pediatric advanced life support : 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2010 Nov 2;122(18 suppl 3):S876-S908.

- 5. Pourmand A, Hill B, Yamane D, Kuhl E. Approach to cardiopulmonary resuscitation induced consciousness, an emergency medicine perspective. Am J Emerg Med 2019 Apr;37(4):751-756.

- 6. Olaussen A, Shepherd M, Nehme Z, Smith K, Bernard S, Mitra B. Return of consciousness during ongoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2015 Jan;86:44-48.

- 7. Olaussen A, Nehme Z, Shepherd M, Jennings PA, Bernard S, Mitra B, et al. Consciousness induced during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: an observational study. Resuscitation 2017 Apr;113:44-50.

- 8. Olaussen A, Shepherd M, Nehme Z, Smith K, Jennings PA, Bernard S, et al. CPR-induced consciousness: a cross-sectional study of healthcare practitioners’ experience. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2016 Nov;19(4):186-190.

- 9. Versteeg J, Noordergraaf J, Vis L, Willems P, Bremer R. CPR-induced consciousness: attention required for caregivers and medication. Resuscitation 2019 Sep;142:e35.

- 10. Pound J, Verbeek PR, Cheskes S. CPR induced consciousness during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a case report on an emerging phenomenon. Prehosp Emerg Care 2017 Mar-Apr;21(2):252-256.

- 11. Gray R. Consciousness with cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Can Fam Physician 2018 Jul;64(7):514-517.

- 12. Parnia S, Spearpoint K, de Vos G, Fenwick P, Goldberg D, Yang J, et al. AWARE-AWAreness during REsuscitation-a prospective study. Resuscitation 2014 Dec;85(12):1799-1805.

- 13. Parnia S, Spearpoint K, Fenwick PB. Near death experiences, cognitive function and psychological outcomes of surviving cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2007 Aug;74(2):215-221.

- 14. Parnia S, Fenwick P. Near death experiences in cardiac arrest: visions of a dying brain or visions of a new science of consciousness. Resuscitation 2002 Jan 1;52(1):5-11.

- 15. Rice DT, Nudell NG, Habrat DA, Smith JE, Ernest EV. CPR induced consciousness: It’s time for sedation protocols for this growing population. Resuscitation 2016 Jun;103:e15-e16.