The eyelids are mobile, flexible structures that cover the globe anteriorly. They serve a vital function by protecting the globe, provide fundamental elements of the precorneal tear film, and distribute the tear film evenly over the surface of the globe. Congenital eyelid anomalies may not only affect vision but can also impair quality of life. Therefore, any esthetic or reconstructive surgery on the eyelid requires a thorough knowledge of eyelid anatomy and embryology.1 In this article, we review eyelid embryology, the most common congenital and developmental eyelid anomalies, and the modalities available to manage these conditions.

Eyelid embryology

The eyelids begin to form by the seventh week of gestation. The ectoderm migrates and folds over, surrounding the optic vesicle. The upper lid is formed by the frontonasal process, while the maxillary process forms the lower lid. The eyelids advance and fuse starting from the center at nine weeks gestation. The fusion leads to the differentiation and development of specialized eyelid structures such as the eyelid margin. Meibomian glands, cilia, and adnexal glands are formed by invaginating ectoderm and mesenchyme around invagination form the tarsus. At 26 weeks gestation, the fused eyelid margins separate. This process is thought to be caused by meibomian gland production, muscle action, and keratinization. The eyelid structures continue to specialize and mature until birth. When the embryological sequence is disrupted, congenital anomalies can occur.2

Congenital eyelid anomalies

Congenital eyelid anomalies, in general, can be classified into malformation of the folds, malformation of the margins, and malformation of the position.

1.malformations of the eyelid folds

Malformations of the eyelid folds include cryptophthalmos, microblepharon, and congenital eyelid coloboma.

Figure 1: Complete form of cryptophthalmos.

Figure 2: Incomplete form of cryptophthalmos where the lower eyelid is present.

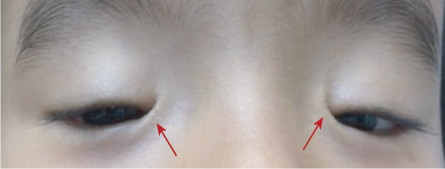

Figure 3: Limbal dermoid in Goldenhar syndrome (red arrow).

Figure 4: Eyelid coloboma (red arrow).

Cryptophthalmos is derived from the Latin word crypt, which means hidden, and the Greek word ophthalmos, which means eye.3 Appropriately, it describes a hidden eye. It is a rare condition with two main variants, complete and incomplete. In the complete form of the condition, which is more prevalent and associated with severe anomalies of the globe, a sheet of skin extends over the disrupted eye from forehead to cheek. There is no differentiation into upper and lower eyelids [Figure 1]. In the incomplete form, the palpebral fissure may be partially formed. However, parts of the lids are not developed and fuse over an abnormally developed globe. In both forms, an ocular cyst may be present. There is a third form called abortive cryptophthalmos or congenital symblepharon. In this form, the upper lid is absent, with a fold of skin from the forehead fused with the underlying cornea. There may be corneal keratinization in the area of the superior symblepharon, but the inferior cornea is usually clear. The lower lid in this form is usually present [Figure 2]. Cryptophthalmos may be unilateral or bilateral, and isolated or syndromic. The condition is seen in 80% of individuals with Fraser syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by cryptophthalmos, cutaneous syndactyly, malformations of the larynx and genitourinary tract, craniofacial dysmorphism, and developmental delay.4

Reconstruction is complicated due to the absence of structural elements of the lids. Orbital imaging must be performed and visual potential assessed preoperatively. In most cases, there is no visual potential. Reconstruction involves a step-wise approach. First, local skin flaps or grafts may be used to reconstruct the anterior lamella. Second, mucous membrane grafts from the mouth or nose are used to reconstruct the posterior lamellar surface.5 The eyeball may be retained to promote orbital development.

1.2 Microblepharon

Microblepharon is a rare condition in which the eyelids are normally formed, but there is vertical shortening. Unlike cryptophthalmos, the underlying globe is normal. The lid shortening results in incomplete lid closure. When severe, it can be associated with ectropion, lagophthalmos, and corneal exposure. Any intervention should be planned according to the severity of the condition. Vertical lengthening of the lids is the surgical procedure of choice. Hard palate graft is used for posterior lamella, and skin graft from other areas is used for the anterior lamella.1,3

1.3Congenital eyelid coloboma

Another sequela of malformation of the fold is congenital eyelid coloboma. The defect may range from simple notching at the lid margin to the complete absence of a lid segment. They are caused by failure of fusion of the embryonic lid folds and may be equivalent to facial clefts. Intrauterine factors play a major role, and amniotic membrane bands may cause mechanical disruption of developing eyelids. The entity can be unilateral or bilateral, symmetrical or asymmetrical, and may occur in isolation or association with other ocular, facial deformities, or syndromes, including Goldenhar syndrome [Figure 3], Fraser syndrome, Treacher Collins syndrome, and CHARGE syndrome.3,6 Eyelid coloboma with associated syndromes were found to have significant ocular associations.6 Eyelid coloboma may involve one or all four lids but most commonly occurs at the junction of the middle and inner one-third of the upper eyelid [Figure 4].

Eyelid coloboma may represent one of the few oculoplastic emergencies encountered at a very early age. In smaller defects, lubrication is often acceptable initially to delay repair until six months of age. This minimizes anesthesia risks and allows for some growth of the child’s lids and other facial structures, thereby facilitating easier surgical repair. Large defects pose a significant threat to the ocular integrity and carry a risk of vision loss from corneal exposure. In such cases, one should maintain a very low threshold for immediate surgical reconstruction, considering the significant risk of amblyopia and a more prominent form of visual loss due to corneal exposure. Surgical intervention depends on the size of the coloboma. For small defects up to 25%, direct closure may suffice. For moderately sized defects (25–50%), a severing of the upper crust of the lateral canthal tendon is required for satisfactory closure. For larger defects (50% or more of the eyelid), available options include eyelid sharing procedures such as the Cutler-Beard procedure, eyelid rotational flap, or a tarsomarginal graft.7,8

2.Malformations of the eyelid margin

Malformation of the eyelid margin covers distichiasis, ankyloblepharon, and tarsal kink syndrome.

2.1Distichiasis

The presence of a partial or complete accessory row of eyelashes growing out of or slightly posterior to the meibomian gland orifices is known as distichiasis. Two types of distichiasis can be identified, acquired and congenital. The congenital form is often dominantly inherited with complete penetrance. It may be related to a failure of the epithelial germ cells to differentiate into meibomian glands; instead, they become pilosebaceous units.9 The congenital form is almost always associated with lymphedema distichiasis syndrome, an autosomal-dominant condition resulting from mutations in the FOXC2 gene.10 The acquired form is seen in chronic inflammatory conditions such as blepharitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

The eyelashes in distichiasis can be fully formed or very fine, pigmented or nonpigmented, and properly oriented or misdirected. In the congenital form, the abnormal lashes tend to be thinner, shorter, softer, and less pigmented than normal cilia and are often well tolerated.5 Acquired distichiasis is more likely to be symptomatic. In the lymphedema distichiasis syndrome, distichiasis is associated with lymphedema of the extremities, which has a later onset (after 10 years of age). Other findings may include congenital heart disease, webbing of the neck, and extradural spinal cysts.

Treatment is indicated if corneal irritation is present. Conservative treatment with lubricants can be given as a trial before surgery. Surgical options include electrolysis for cases with few aberrant eyelashes. Other options include a combination of lid splitting and cryotherapy to the posterior lamella, direct surgical excision by wedge resection, or the tarsoconjunctival approach.11

2.2Ankyloblepharon

Ankyloblepharon is the total or partial fusion of eyelids by webs of skin due to failure of the eyelid to separate completely during embryogenesis. When the adhesion is at the lateral canthus, it is called external ankyloblepharon. When it occurs at the medial canthus, it is called an internal ankyloblepharon.3 When multiple small strands are in the middle of the margin, the defect is called ankyloblepharon filiforme adnatum [Figure 5].12 The currently accepted theory is that this condition is due to temporary epithelial arrest and rapid mesenchymal proliferation, allowing union of eyelids at abnormal positions.13

Figure 5: Ankyloblepharon filiforme adnatum, a red arrow showing a strand in the middle margin of the right eye.

Figure 6: Bilateral ptosis.

Ankyloblepharon may be an isolated sporadic malformation or may be associated with other inherited conditions. The eyelids and eyeballs are often normal. Rarely, ankyloblepharon has been reported to be associated with infantile glaucoma and irido dysgenesis.3 Ankyloblepharon may be associated with the central nervous system and/or cardiac anomalies, ectodermal syndromes, cleft lip and/or palate, popliteal pterygium syndrome, and gastrointestinal abnormalities.14

Fine filamentous adhesions of ankyloblepharon filiforme adnatum may resolve spontaneously.12 Surgery is indicated if there is a possibility of amblyopia due to visual deprivation. The fine bands of adhesions can be broken by forcibly separating the lids or using a muscle hook, sharp scissors, or a scalpel. The remnants at the lid margin usually shrink and resolve. Bipolar cautery forceps can be used at the bases of fine filaments to release the adhesions. More severe cases of congenital ankyloblepharon require reconstructive surgery involving separation and reconstruction of the lid margins.15

2.3Tarsal kink syndrome

Tarsal kink syndrome is a rare and severe form of congenital upper eyelid entropion with unknown etiology characterized by horizontal kink or bend of tarsus within the upper tarsal plate. Proposed causes include overaction of the marginal fibers of the orbicularis muscle causing tarsal infolding in utero, an aponeurotic defect, a primary tarsal defect, an eyelid disjunction defect in utero, or an exogenous mechanical cause in utero.16 Tarsal kink syndrome may be associated with trisomy 13.17

The inversion of the eyelid margin is characterized by blepharospasm and absence of an upper eyelid fold. Corneal ulceration by the folded edge of the upper tarsus or the in-turned eyelids and eyelashes occurs if not corrected by surgery.

Early recognition and treatment of entropion is essential to reduce the risk of corneal scarring and amblyopia. Surgery is usually required to prevent damage to the cornea. The surgical goal involves weakening the tarsal kink with excision, lamellar tarsoplasty, eyelid everting sutures, tarso-conjunctival tarsotomy with margin rotation, and eyelid crease formation.18

3.Malformations of the position

Malformation of the eyelid position encompasses congenital ptosis, blepharophimosis syndrome, epicanthal fold, euryblepharon, epiblepharon, entropion, and ectropion.

3.1Congenital ptosis

Ptosis represents the most common eyelid malposition in children.3 Normal upper eyelid position is 1–2 mm below the superior limbus. In ptosis, the upper eyelid falls to a lower position than normal, thus creating a vertical shortening of the palpebral fissure. In severe cases, the drooping eyelid can cover part of or the entire pupil and interfere with vision, resulting in amblyopia in young children. Ptosis can be congenital or acquired, unilateral or bilateral [Figure 6]. Congenital ptosis can be primary or secondary. Most cases of congenital ptosis are idiopathic and are termed primary. Congenital primary ptosis is associated with dysgenesis of the levator palpebrae superioris.19 Normal levator muscle fibers are replaced by fibrous and adipose tissue, diminishing the muscle’s ability to contract and relax. Therefore, the condition is commonly called congenital myogenic ptosis. Secondary or acquired ptosis includes aponeurotic, neurogenic, mechanical, and traumatic. Congenital ptosis may be familial. Anisometropic amblyopia and strabismus are common associations.19

All patients with ptosis should undergo full ophthalmic examination, including vision, cycloplegic refraction, orthoptic exam, anterior segment, and dilated fundus exam. The four important clinical measurements related to ptosis include margin–corneal reflex distance, vertical palpebral fissure height, upper eyelid crease position, and levator function. These signs should be recorded for each child in each visit. Evaluation of extraocular muscles function, synertistic movements, pupillary reaction, corneal reflex, lagophthalmos, and Bell's phenomenon is important to document while planning surgery.

Correction of mild or moderate ptosis can usually be delayed until age four to five years old. Severe ptosis that obstructs vision must be corrected early in infancy to prevent deprivation amblyopia. The amount of ptosis and the degree of levator function are the most common determining factors in the choice of surgical procedure for ptosis repair. Surgical techniques include external levator muscle resection, levator muscle advancement or tuck, mullerectomy, and frontalis suspension. Frontalis suspension is usually performed when levator muscle function is < 4 mm.20,21

3.2Blepharophimosis, ptosis, and epicanthus inversus syndrome (BPES)

Also called blepharophimosis syndrome, the condition consists of four classic signs: blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus, and telecanthus [Figure 7]. It is an autosomal dominant condition caused by mutations in the FOXL2 gene on chromosome 3q2314. It may be isolated or part of various syndromes (fetal alcohol syndrome, Ohdo syndrome, and chromosome 3p deletion). There are two types of BPES. Type 1 is associated with menstrual irregularity and infertility due to premature ovarian failure and is transmitted only by males. Type 2 has no systemic associations and can be transmitted by both genders.22

Figure 7: Blepharophimosis syndrome.

Figure 8: Bilateral epicanthus inversus (red arrows).

In blepharophimosis, the palpebral fissures are shortened horizontally and vertically. Ptosis is severe with poor levator function and absent eyelid fold. Additional findings may include lateral lower eyelid ectropion secondary to vertical eyelid deficiency, a poorly developed nasal bridge, hypoplasia of the superior orbital rims, ear deformities, and hypertelorism. Female patients with blepharophimosis should be evaluated for ovarian dysfunction. They should also be monitored later in life for menstrual irregularity.3

The timing of surgical correction is based on the child’s visual acuity. Prompt surgical correction of the eyelid malformations in children with severe ptosis can help prevent visual impairment secondary to amblyopia. Once amblyopia is ruled out, staged management of the eyelid malformations typically involves correcting the epicanthus inversus and telecanthus at three to five years of age, followed by ptosis correction one year later. Multiple Z-plasties or Y–V-plasties, sometimes combined with transnasal wiring of the medial canthal tendons, are used to modify the telecanthus and epicanthus. Repair of the ptosis usually requires frontalis suspension for adequate lift. Additional procedures may be necessary to correct ectropion or orbital rim hypoplasia.23

3.3 Epicanthus

Epicanthal folds are oblique or vertical folds from the upper or lower eyelids towards the medial canthus. Usually bilateral and may involve both the upper and lower lids. These folds are caused by excessive development of the skin across the bridge of the nose. They are classified into four subtypes based on the origin and termination of the folded tissue. Epicanthus tarsalis describes a fold most prominent along the upper eyelid and fanning into the medial canthus. This variant is a normal anatomic variant of the Asian eyelid. Epicanthus inversus describes a fold that is most prominent along the lower eyelid and is associated with the blepharophimosis syndrome [Figure 8]. In epicanthus palpebralis, the fold is equally distributed between the upper and lower eyelids. Epicanthus superciliaris is the fourth subtype where the skin fold originates from the eyebrow and follows down to the lacrimal sac. Epicanthus may be associated with various other conditions such as blepharophimosis, ptosis, Down syndrome, or might appear as an isolated finding.3 Children with prominent epicanthal folds may appear esotropic due to decreased scleral show nasally, giving rise to what we describe as a pseudostrabismus.24

Surgical correction is only occasionally required and is mainly cosmetic. Frequently, a mild degree of epicanthus is observed in children and is generally temporary as the folds disappear with further development of the nose and mid-facial bones. However, epicanthus inversus rarely resolves with growth. Observation is usually recommended until maturation of the face if no other eyelid abnormalities are present. The goal of epicanthal fold repair is to eliminate the fold adhesions and produce a concave contour to the medial canthal region. The basic surgical principle is tissue rearrangement to lengthen the vertical component of the fold. Surgical treatment for most isolated epicanthus is achieved by linear revisions, such as Z-plasties or even a Y-V-plasties.25

3.4 Euryblepharon

Euryblepharon is derived from the Latin root eury (wide) and the Greek word blepharon (pertaining to the eyelid) and describes enlarged palpebral fissures.3 Typically, it is associated with horizontal widening of the palpebral fissure, and vertical shortening and horizontal lengthening of the involved eyelids. The lateral portion of the eyelids is typically more involved than the medial aspect. The palpebral fissure often has a downward slant because of the inferiorly displaced lateral canthal tendon. Additional findings may include proximal displacement of the lacrimal system, a double row of meibomian gland orifices, telecanthus, and strabismus. Euryblepharon may be associated with blepharophimosis syndrome and Kabuki syndrome. Impaired blinking, poor closure, and lagophthalmos may result in exposure keratitis. This condition must be differentiated from other causes of ectropion or lateral canthal dystopia, such as clefting syndromes.26 Surgery aims to reduce exposure. If the condition is symptomatic, reconstruction may include lateral canthal repositioning and suspension of the suborbicularis oculi fat to the lateral orbital rim so that the lower eyelid is supported. If excess horizontal length is still apparent, a lateral tarsal strip or eyelid margin resection may be added. Skin grafts may occasionally be necessary.27

3.5 Epiblepharon

Epiblepharon is a developmental lower eyelid condition characterized by redundant anterior lamella presenting as an abnormal horizontal skin fold overriding the eyelid margin, resulting in misdirected lashes towards the conjunctiva and cornea [Figure 9]. It is common but not exclusive in Orientals, and should not be confused with the much less common congenital entropion.3 The condition can be seen in the upper eyelid, but to a lesser extent compared to the lower one. Unlike congenital entropion, the tarsal plate is not inverted. Around 50% of children develop with the rule astigmatism; 80% of patients with epiblepharon will have no ocular symptoms.28 Epiblepharon may require no surgical treatment because it tends to diminish with facial growth. Most children are asymptomatic as the eyelashes are fine and may not induce keratopathy even with lash-corneal touch. As the lashes get thicker and longer and with increasing skin fold, especially in those with higher body mass index, epiblepharon occasionally results in acute or chronic corneal epithelial irritation, photophobia, or keratitis. In mild cases, lubrication may suffice. In severe cases, the excess skin and muscle are excised just inferior to the eyelid margin. The most commonly recommended procedure is the modified Hotz procedure, which involves excision of an ellipse of redundant skin mostly medially, with sutures placed to ensure outward rotation of the eyelashes with wound closure.29

3.6 Ectropion

Figure 9: Bilateral epiblepharon syndrome (red arrows).

Figure 10: Bilateral ectropion in ichthyosis.

Figure 11: Bilateral ectropion with complete eversion of the upper lids.

1.1Cryptophthalmos

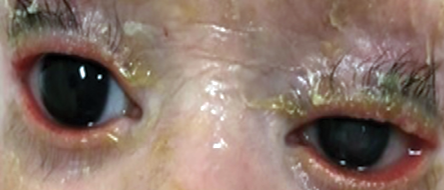

Ectropion is an outward turning of the eyelid margin, which primarily involves the lower lid. Congenital ectropion rarely occurs as an isolated finding. It is more often associated with blepharophimosis syndrome, Down syndrome, or ichthyosis [Figure 10]. Complete eversion of the upper eyelids occasionally occurs in newborns and is due to vertical insufficiency of the anterior lamella of the lid [Figure 11]. It is a rare condition, typically bilateral, and is seen more frequently in black infants, children with Down syndrome, and collodion babies. Primary ectropion results from absence or atrophy of the tarsal plate. Secondary ectropion results from paralytic, cicatricial, or mechanical causes.3,30

Congenital ectropion can cause chronic ocular irritation because of the lack of lid apposition to the globe, with subsequent tear film insufficiency chronic dry eye, and corneal irritation. In addition, chronic lid ectropion can lead to keratinization of the palpebral conjunctiva requiring conjunctivoplasty.

Chlamydia trachomatis has been implicated in patients with complete eyelid eversion, and appropriate conjunctival smears and stains should be performed to rule out this condition.3 Mild forms of congenital ectropion often may be managed with lubricants. Surgical management is indicated in severe and symptomatic patients. If horizontal laxity is present, a lid-shortening procedure with a lateral canthoplasty can be used to invert the eyelid margin. When there is a true shortening of the anterior lamella, as in ichthyosis, a skin graft using preauricular or postauricular skin, for example, may be required. But this often does not result in an optimal cosmetic outcome.3,30

3.7 Entropion

Congenital entropion is a rare condition in which the lower eyelid margin is rotated inward since birth. Chronic entropion can cause chronic irritation, corneal scarring, and subsequent vision loss. Congenital entropion may be due to retractor malformation, structural defects in the tarsal plate, or shortening of the posterior lamella. Children may also develop entropion following facial paralysis.3 In pediatric patients, the orbicularis oculi muscle acts to counter the in turning force of the lower lid retractors. Facial paralysis results in unchecked retractor function rotating the eyelid margin toward the globe surface.31 Congenital entropion must be distinguished from epiblepharon, as this may help determine the severity of the condition and the need for intervention. The eyelashes in epiblepharon are typically vertically oriented instead of the inward directing of the lashes in entropion from an actual rotation of the lid margin. Epiblepharon can improve with age as a child grows, while congenital entropion rarely resolves spontaneously and worsens with age.28 A lower eyelid entropion may be repaired by removing an ellipse of skin and orbicularis and suturing the lower lid retractors to the tarsus. Upper lid entropion repair can be accomplished through a skin and orbicularis incision to the tarsus and rotation of the lid margin.30

Conclusion

Congenital eyelid abnormalities are not uncommon. They are considered among the most challenging problems encountered by reconstructive surgeons. Comprehensive knowledge of both embryology and anatomy is crucial in planning the management. Surgical management is indicated to prevent complications and amblyopia. A detailed eye examination is indicated. Selected children should be referred to the pediatrician to rule out systemic conditions. Genetic evaluation may also be warranted.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Guercio JR, Martyn LJ. Congenital malformations of the eye and orbit. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2007 Feb;40(1):113-140.

- 2. Tawfik HA, Abdulhafez MH, Fouad YA, Dutton JJ. Embryologic and fetal development of human eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2016 Nov/Dec;32(6):407-414.

- 3. Katowitz WR, Katowitz JA. Congenital and developmental eyelid abnormalities. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009 Jul;124(1 Suppl):93e-105e.

- 4. Walton WT, Enzenauer RW, Cornell FM. Abortive cryptophthalmos: a case report and a review of cryptophthalmos. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1990 May-Jun;27(3):129-132.

- 5. Subramanian N, Iyer G, Srinivasan B. Cryptophthalmos: reconstructive techniques–expanded classification of congenital symblepharon variant. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2013 Jul-Aug;29(4):243-248.

- 6. Tawfik HA, Abdulhafez MH, Fouad YA. Congenital upper eyelid coloboma: embryologic, nomenclatorial, nosologic, etiologic, pathogenetic, epidemiologic, clinical, and management perspectives. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2015 Jan-Feb;31(1):1-12.

- 7. Lin LK, Martin J. State of the art in congenital eyelid deformity management. Facial Plast Surg 2016 Apr;32(2):142-149.

- 8. Hoyama E, Limawararut V, Malhotra R, Muecke J, Selva D. Tarsomarginal graft in upper eyelid coloboma repair. J AAPOS 2007 Oct;11(5):499-501.

- 9. Alkatan HM, Galindo-Ferreiro A, Maktabi A, Galvez-Ruiz A, Schellini S. Congenital distichiasis: histopathological report of 3 cases. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2017 Jul-Sep;31(3):165-168.

- 10. De Niear MA, Breazzano MP, Mawn LA. Novel FOXC2 mutation and distichiasis in a patient with lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2018 May/Jun;34(3):e88-e90.

- 11. Rozenberg A, Pokroy R, Langer P, Tsumi E, Hartstein ME. Modified treatment of distichiasis with direct tarsal strip excision without mucosal graft. Orbit 2018 Oct;37(5):341-343.

- 12. Chakraborti C, Chaudhury KP, Das J, Biswas A. Ankyloblepharon filiforme adnatum: report of two cases. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2014 Apr-Jun;21(2):200-202.

- 13. Sawardekar SS, Zaenglein AL. Ankyloblepharon-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting syndrome: a novel p63 mutation associated with generalized neonatal erosions. Pediatr Dermatol 2011 May-Jun;28(3):313-317.

- 14. Malpas T, Singh D, Sarvasiddhi S, Lawrenson D, Wellesley D. Cleft lip and palate with lip pits and ankyloblepharon. J Paediatr Child Health 2017 Sep;53(9):919.

- 15. Ioannides A, Georgakarakos ND. Management of ankyloblepharon filiforme adnatum. Eye (Lond) 2011 Jun;25(6):823.

- 16. Sires BS. Congenital horizontal tarsal kink: clinical characteristics from a large series. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 1999 Sep;15(5):355-359.

- 17. Lucci LM, Fukumoto WK, Alvarenga LS. Trisomy 13: a rare case of congenital tarsal kink. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2003 Sep;19(5):408-410.

- 18. Naik MN, Honavar SG, Bhaduri A, Linberg JV. Congenital horizontal tarsal kink: a single-center experience with 6 cases. Ophthalmology 2007 Aug;114(8):1564-1568.

- 19. Jubbal KT, Kania K, Braun TL, Katowitz WR, Marx DP. Pediatric blepharoptosis. Semin Plast Surg 2017 Feb;31(1):58-64.

- 20. Al-Mujaini A, Wali UK. Total levator aponeurosis resection for primary congenital ptosis with very poor levator function. Oman J Ophthalmol 2010 Sep;3(3):122-125.

- 21. Al-Mujaini A, Shenoy K, Wali U. Ptosis surgery: complications that might happen. Inter J Ocular Oncolog Oculoplast. 2016;2(4):219-221.

- 22. Tyers AG. The blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome (BPES). Orbit 2011 Oct;30(5):199-201.

- 23. Betharia SM, Dayal Y, Kalra BR. Surgical management of blepharophimosis syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol 1983 Jul;31(4):339-341.

- 24. Park JW, Hwang K. Anatomy and histology of an epicanthal fold. J Craniofac Surg 2016 Jun;27(4):1101-1103.

- 25. Li G, Wu Z, Tan J, Ding W, Luo M. Correcting epicanthal folds by using asymmetric Z-plasty with a two curve design. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2016 Mar;69(3):438-440.

- 26. Fountain TR, Goldberger S. A case of bilateral cryptophthalmia and euryblepharon with two-stage reconstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2001 Jan;17(1):53-55.

- 27. Markowitz GD, Handler LF, Katowitz JA. Congenital euryblepharon and nasolacrimal anomalies in a patient with Down syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1994 Sep-Oct;31(5):330-331.

- 28. Kakizaki H, Leibovitch I, Takahashi Y, Selva D. Eyelash inversion in epiblepharon: is it caused by redundant skin? Clin Ophthalmol 2009;3:247-250.

- 29. Woo KI, Kim YD. Management of epiblepharon: state of the art. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2016 Sep;27(5):433-438.

- 30. Fea A, Turco D, Actis AG, De Sanctis U, Actis G, Grignolo FM. Ectropion, entropion, trichiasis. Minerva Chir 2013 Dec;68(6)(Suppl 1):27-35.

- 31. Alsuhaibani AH, Bosley TM, Goldberg RA, Al-Faky YH. Entropion in children with isolated peripheral facial nerve paresis. Eye (Lond) 2012 Aug;26(8):1095-1098.