A45-year-old painter was admitted with a five day-history of a dry cough, headache, shortness of breath, and fever. His complaints started 10 days after he finished the remodeling of an old house. His physical exam was non-focal, and he had no rashes or lymphadenopathy. His blood tests showed white blood cell count of 12.7 × 109/μL and his kidney and liver function tests were within normal limits. Lumbar puncture results and human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) test were negative.

His chest X-ray showed bilateral interstitial opacities. Lung computed tomography scans showed bilateral parenchymal micronodules. The patient’s blood and bronchoalveolar lavage cultures were negative. He was diagnosed with atypical community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and discharged on a course of azithromycin.

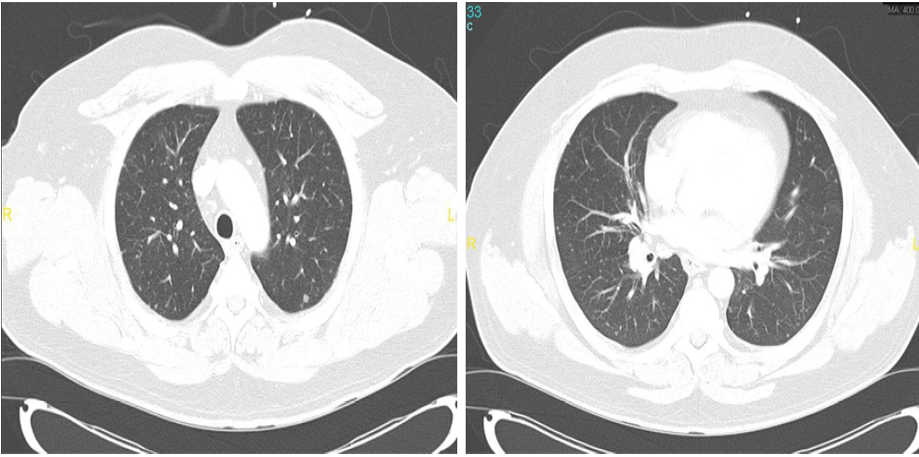

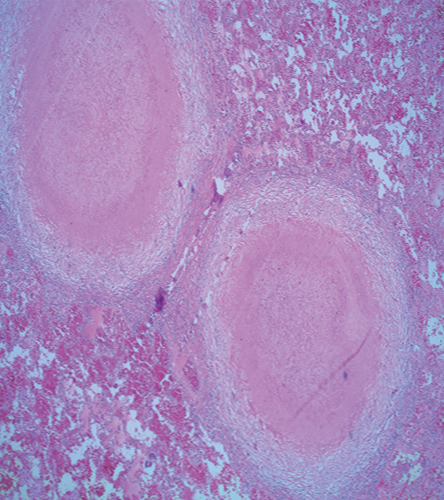

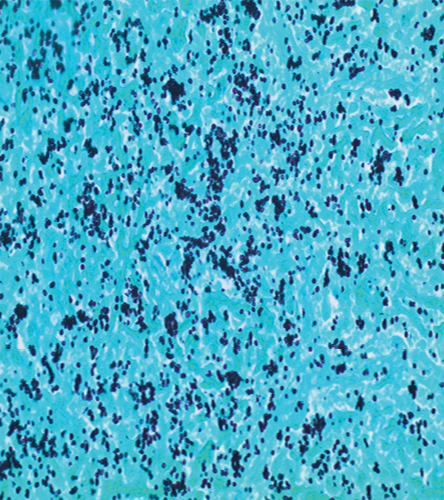

The patient was lost to follow-up until he presented to our hospital four months later with constitutional symptoms. He reported night sweats and fever, poor appetite, dry cough, and shortness of breath. Follow-up chest imaging showed an increase in the size of the pulmonary nodules [Figure 1a and 1b]. He underwent video-assisted thoracoscopy with a lung biopsy. Biopsy staining is shown in Figure 2 and 3.

Questions:

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Answer

The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary histoplasmosis. He initially presented with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis that progressed to chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis. His lung biopsy grew Histoplasma capsulatum. His urinary histoplasma antigens and serum histoplasma antibodies were negative. He was started on a six-month course of oral itraconazole and discharged. His symptoms improved gradually, and he continues to be followed- up in the outpatient clinic.

Figures 1: Computed tomography scans of two sections of the patient’s chest showing bilateral pulmonary nodules of variable size.

Figure 2: Hematoxylin and eosin stained section of the lung shows two well-defined granulomas with central necrosis, magnification = 40 ×.

Figure 3: Gomori methanamine silver stain shows small budding yeast consistent with histoplasma. The yeast clustering indicates the intracellular location within macrophages, magnification = 400 ×.

Discussion

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum. This ailment is prevalent in Southeast Asia, North and Central Americas, and parts of Europe, Africa, and Australia.1 Fifty to 80% of people living in endemic regions have been exposed to this fungus and have positive serology.1 Histoplasma is abundant in soil and grows as a mold.1 When the fungal spores (microconidia) are inhaled, they vegetate in host tissues causing infection and grow as a yeast.2,3 Most infections are mild and cause flu-like symptoms or are completely asymptomatic.4 Outbreaks of histoplasmosis have been associated with disruption of the ground during construction, visits to endemic areas, exposure to bird or bat guano, and remolding and renovation activities as the contaminated soil remains infectious for years.5-9 Important diseases to consider in the differential diagnosis of histoplasmosis are other endemic mycosis, lymphoma, atypical bacterial pneumonia, and tuberculosis.

In acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, within one to two weeks of exposure, individuals may present with fever, chills, myalgia, loss of appetite, and headaches. A cough, dyspnea, and chest pain may also be present with a variable intensity that is directly related to the degree of compression on the respiratory tree or esophagus by the enlarged regional lymph nodes. Associated skin and joint lesions like erythema nodosum and arthralgias are seen in 5–10% of patients, mostly female, while some develop asymptomatic pleural effusion (10%) or pericarditis (5%).1,2 This condition is self-limiting with rapid improvement in the majority of otherwise healthy patients. On the other hand, in immunocompromised patients and those who have inhaled large quantity of spores, the pulmonary infection involves multiple lobes and can rapidly progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or can spread to other body organs.10

On rare occasions, especially in elderly patients with smoking history, pulmonary histoplasmosis may progress slowly into a chronic form characterized by a cough, low-grade fever, weight loss, night sweats, and malaise. Hemoptysis with massive sputum production may indicate the presence of cavitary lesions. This form usually involves apical regions of the lungs resulting in pleural thickening, volume loss, and fibrosis with scarring. If untreated, this condition carries a poor prognosis resulting from progressive pulmonary insufficiency.2

A small number of patients with apparently normal immune systems and those with immunosuppressive conditions are unable to launch an effective offensive response against the invading organism and develop sub-acute or chronic disseminated histoplasmosis. This may occur either during the initial infection/re-exposure or recrudescence of latent infection, years after leaving the endemic area. Clinical manifestations vary with the duration of illness and result from the granulomatous destruction of organs seeded by the yeast. Interestingly, the pulmonary involvement in disseminated form is not very common. Advanced stages of this condition present as sepsis syndrome with hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, renal failure, and ARDS.3

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be challenging. It hinges on documenting consistent histopathological examination, positive culture results, or positive antigen/antibody testing.10 A recent multicenter study evaluated the tests mentioned in the diagnosis of pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 Pathological examination was consistent with histoplasmosis in 66% to 75% of specimens. Cultures yielded the fungus in more than 80% of samples, antigenuria was present in 40% to 80% of patients, and serology was positive in more than 90% of cases. The role of molecular methods in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis is still under development.12

Antigen detection has significant cross-reactivity with other fungal antigens.13 Cross-reaction occurs in 90% of patients with blastomycosis and 60% of patients with coccidioidomycosis.11 The sensitivity of antigen detection can be enhanced by testing both urine and serum samples. Moreover, testing bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with suspected pulmonary histoplasmosis might improve the sensitivity further.14

Radiographic findings are usually minimal during acute infection. Occasionally, enlarged hilar and mediastinal nodes are seen.15 Diffuse pulmonary involvement with reticulonodular or miliary pattern may be seen on chest radiograph after exposure to the high inoculum. In chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, hilar lymphadenopathy is a rare finding; however, cavitary lesions with emphysematous changes in upper zones can be seen in up to 90% of patients.15 In patients with progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, hilar lymphadenopathy with diffuse nodular opacities resembling miliary tuberculosis is commonly seen.

The illness severity affects the choice and duration of antifungal therapy.16 The treatment of mild acute pulmonary histoplasmosis is usually unnecessary. Treatment with itraconazole for six to 12 weeks is recommended for patients who continue to be symptomatic beyond one month. For moderate to severe acute pulmonary infection, liposomal amphotericin B for one to two weeks followed by 12 weeks of itraconazole is indicated. Patients with chronic lung infection require itraconazole for at least one year. Itraconazole blood levels should be measured after the second week of therapy to ensure adequate drug exposure.16 Ten to 15% of patients experience a relapse, those with a cavitary disease have the highest risk.16 Diagnosis and treatment in this group of patients follows the above-outlined principles.

Those engaged in activities posing a high-risk for catching histoplasmosis such as soil disruption or cleaning bird cages, old building refurbishment or demolition, use of bird droppings as fertilizer, excavation, and camping should take precautions (e.g. using approved respirators, treating soil or debris with formalin, and using water sprays to decrease dust in immediate surroundings).15 Patients with immunosuppression or at the extremes of age should also take similar precautions.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

references

- Knox KS, Hage CA. Histoplasmosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010 May;7(3):169-172.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007 Jan;20(1):115-132.

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980 Jan;59(1):1-33.

- Lowell JR. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Ann Intern Med 1983 Feb;98(2):260.

- Stobierski MG, Hospedales CJ, Hall WN, Robinson-Dunn B, Hoch D, Sheill DA. Outbreak of histoplasmosis among employees in a paper factory–Michigan, 1993. J Clin Microbiol 1996 May;34(5):1220-1223.

- Buxton JA, Dawar M, Wheat LJ, Black WA, Ames NG, Mugford M, et al. Outbreak of histoplasmosis in a school party that visited a cave in Belize: role of antigen testing in diagnosis. J Travel Med 2002 Jan-Feb;9(1):48-50.

- Chamany S, Mirza SA, Fleming JW, Howell JF, Lenhart SW, Mortimer VD, et al. A large histoplasmosis outbreak among high school students in Indiana, 2001. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004 Oct;23(10):909-914.

- Bartlett PC, Vonbehren LA, Tewari RP, Martin RJ, Eagleton L, Isaac MJ, et al. Bats in the belfry: an outbreak of histoplasmosis. Am J Public Health 1982 Dec;72(12):1369-1372.

- Huhn GD, Austin C, Carr M, Heyer D, Boudreau P, Gilbert G, et al. Two outbreaks of occupationally acquired histoplasmosis: more than workers at risk. Environ Health Perspect 2005 May;113(5):585-589.

- Wheat J. Histoplasmosis. Experience during outbreaks in Indianapolis and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1997 Sep;76(5):339-354.

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, Baddour LM, Assi M, McKinsey DS, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011 Sep;53(5):448-454.

- Bracca A, Tosello ME, Girardini JE, Amigot SL, Gomez C, Serra E. Molecular detection of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum in human clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol 2003 Apr;41(4):1753-1755.

- Connolly PA, Durkin MM, Lemonte AM, Hackett EJ, Wheat LJ. Detection of histoplasma antigen by a quantitative enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2007 Dec;14(12):1587-1591.

- Hage CA, Wheat LJ. Diagnosis of pulmonary histoplasmosis using antigen detection in the bronchoalveolar lavage. Expert Rev Respir Med 2010 Aug;4(4):427-429.

- Hage CA, Wheat LJ, Loyd J, Allen SD, Blue D, Knox KS. Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2008 Apr;29(2):151-165.

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007 Oct;45(7):807-825.