|

INTRODUCTION

Trichobezoars, commonly occur in patients with psychiatric disturbances who chew and swallow their own hair. Only 50% give a history of trichophagia. Trichobezoars have been described in literature and they comprise 55% of all bezoars. In very rare cases, the hair ball extends through the pylorus into the small bowel causing signs and symptoms of partial or complete gastric/intestinal obstruction,1 a condition aptly described as “Rapunzel Syndrome.”

CASE REPORT

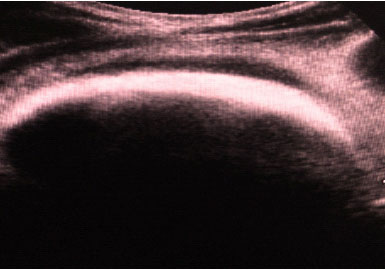

A young adolescent female presented with an eight-month history of pain and distention of the upper abdomen and intermittent vomiting. On examination, a firm epigastric lump was palpable. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed a superficially located broad band of high-amplitude echoes along the anterior wall of the mass, with a sharp, clean posterior acoustic shadowing precluding complete evaluation.

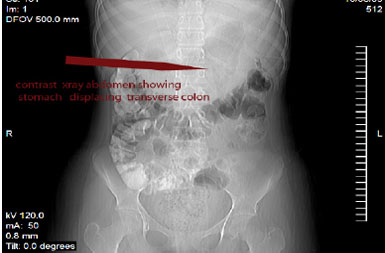

The upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast series revealed a large, mottled, filling defect in the stomach extending into the third part of the duodenum, (Figs. 1 and 2). Apart from the mottled filling defect, an upper GI study showed the positive density of the mass with a lace-like pattern due to residual contrast medium on delayed films. Fluoroscopic examination with the patient in the erect position showed the swallowed barium held up in the cardiac end of the stomach for a few seconds, and then the contrast was seen to diffuse slowly downwards on either side of the non-opaque foreign body and followed the regular contours of the greater and lesser curvatures to mapping out the normal contour of the stomach. Abdominal Computed Tomography was performed to further define the pathology.

Figures 1: Plain X-ray Abdomen Showing soft tissue density in the region of stomach.

Figures 2: Contrast study abdomen showing stomach displacing the transverse colon.

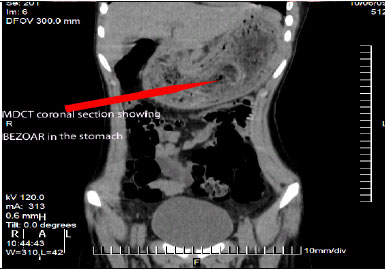

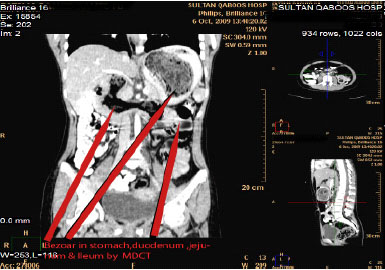

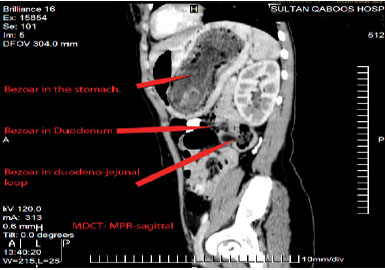

The normal stomach wall could be traced around the lesion, (Figs. 4). The stomach showed intraluminal hypodense mesh like pattern. Oral contrast was sparse within the mesh, though prominent around the margins, (Fig. 5). The presence of a tail was reflected by small areas of rounded hypodensity in parts of the small bowel, (Fig. 6). There was an absence of any significant contrast enhancement following the administration of intravenous contrast material. Surgical removal was performed through Lap assisted gastrotomy. (Fig. 7)

Figures 3: USG showing Bezoar

Figures 4: MDCT Plain abdomen showing Bezoar

Figures 5: MDCT Contrast abdomen showing Rapuzel features

Figures 6: MDCT-MPR showing Bezoar in duodenum, jejunum and ileal loops

Figures 7: Bezoar Specimen showing tail

DISCUSSION

The term Rapunzel syndrome was coined by Vaughan et al. in 1968, for an unusual manifestation of a Trichobezoar in which the mass extends from the stomach and duodenum through a large portion of the small intestine.1 The term Bezoar comes from the Arabic Badzehr or from the Persian Panzer, both meaning counterpoison and antidote.2 Trichobezoar should be borne in mind when the patient is a young female especially when it is accompanied by alopecia and trichophagy.3 Bezoars in the 12th century BC was used for rejuvenating the old, neutralizing snake venom and other poisons, treating vertigo, epilepsy, melancholia, and even plague.

Bezoars are named after the substances that produce them. Hair (Trichobezoar), Vegetable fibers (Phytobezoar), Persimmon fibers (Diospyrobezoar) and Tablets/semi-liquid masses of drugs (Pharmacobezoar) are some of the examples.4 Bezoars mostly originate in the stomach, probably due to their capacity and are related to an abnormal diet pattern. They generally cause nonspecific symptoms such as epigastric pain, dyspepsia, and postprandial fullness. The patient may present with a palpable, firm, non tender epigastric mass, which may be discovered on routine physical examination in an asymptomatic patient or may be an operative surprise. Patients may also present with GI bleeding (6%) and intestinal obstruction or perforation (10%).5.6 Some patients with trichobezoar show overt mental disturbance or personality disorders and clinically present with an epigastric mass.

Ultrasound features are not pathognomonic. A hyperechoic curvilinear dense strip with acoustic shadowing and no through transmission are the features usually seen.

Trichobezoars are best identified on oral contrast studies and Computed Tomography.7 Computed Tomography best reveal the size and configuration of the bezoar and most accurately identify its location. Furthermore, the highly characteristic Computed Tomography appearance showed ready differentiation from other pathologies (such as intra or extragastric neoplasms) that would be difficult on plain radiography or on ultrasound.8 The treatment of large bezoars and concretions is essentially surgical via gastrotomy. Duncan et al. recommended bezoar extraction by multiple enterotomies in cases of Rapunzel syndrome.9 It is mandatory to do a thorough exploration of the rest of the small intestine and the stomach to look for retained bezoars. The patient’s psychological problems also need to be dealt with to prevent recurrence. In recent years, more and more such cases have been reported.10,11

CONCLUSION

Rapunzel syndrome is an extremely uncommon variant of Trichobezoar. It is also an uncommon cause of bowel obstruction, especially in young females. Pre-operative diagnosis of this condition is possible by imaging modalities especially Computed Tomography with oral contrast. Surgery is the mainstay in treatment. Prophylaxis against recurrence should be by proper psychiatric counseling and monitoring as in most cases there is an underlying mental disorder in such patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Logesan Dhinakar of Sultan Qaboos Hospital for his support. The authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding was received on this work.

|