Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease (KFD), also called Kikuchi histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a clinicopathologic diagnosis characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy that usually follows a self-limiting course. As the name implies, lymph node microscopic examination shows foci of necrosis and histiocytic cellular infiltrate. It predominantly affects young females with a male-to-female ratio of 1:4.1,2 Given its association with auto immune diseases, it is essential to exclude systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which may present concomitantly or several years after the diagnosis

of KFD.1

Besides lymphadenopathy, other frequently reported symptoms included fever (35%), malar rashes (10%), fatigue (7%), and joint pain (7%).3 Regarding blood investigations, common abnormalities reported included leukopenia (18%), high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (16%), and anemia (9%).3 KFD can also present with thrombocytopenia, a normal count, and sometimes with thrombocytosis.4 KFD may carry the risk of thrombophilia and thrombosis or association with Budd-Chiari syndrome if there is a concomitant presentation with SLE/APLS.5

Case report

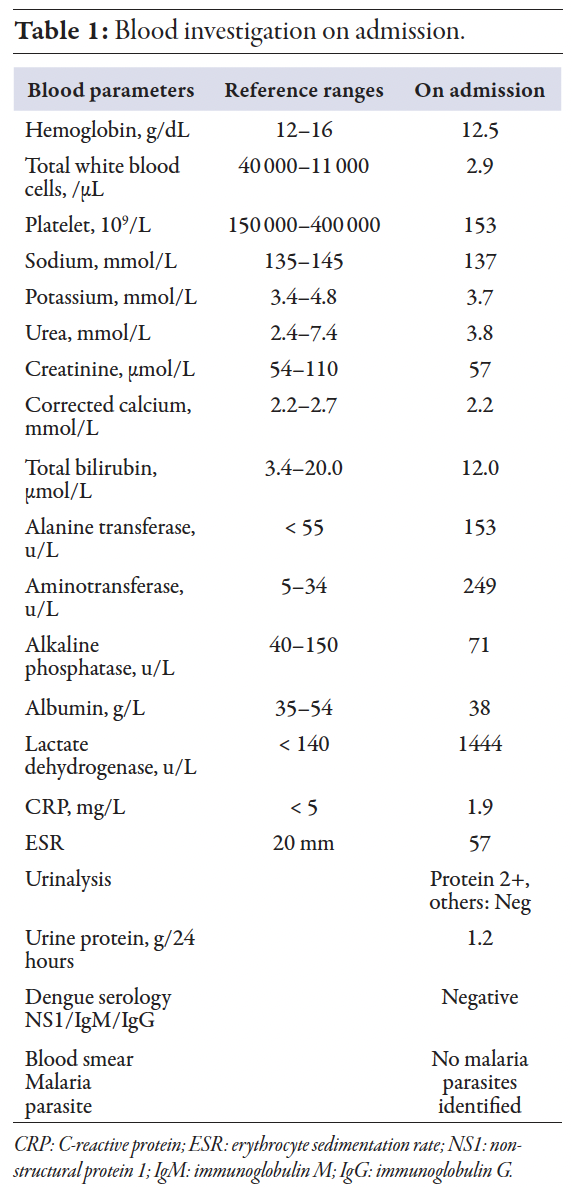

A previously healthy 26-year-old woman, working as an assistant pharmacist, presented with a complaint of fever for two weeks, associated with intermittent abdominal discomfort, loose stool, and vomiting. She reported a loss of appetite and a weight loss of about 6 kg within two weeks. She noticed multiple neck swellings that were gradually increasing in size, and multiple symmetrical polyarthralgia. She denied alopecia, oral ulcers, photosensitivity rash, and a previous history of tuberculosis or tuberculosis contacts. There was no family history of connective tissue disorders. On clinical assessment, she had bilateral cervical lymphadenopathies, which were mobile, non-tender, and non-matted, with the largest node measuring about 2 × 2 cm. There were no enlarged lymph nodes elsewhere or hepatosplenomegaly present. Her initial laboratory investigations revealed leukopenia, transaminitis, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [Table 1]. The differential diagnosis at that time was lymphoproliferative disease or tuberculosis lymphadenitis. Further workup for lymphadenopathy was done. Her chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. An otolaryngology consult was obtained for the neck swelling. A nasal endoscopy showed no abnormalities.

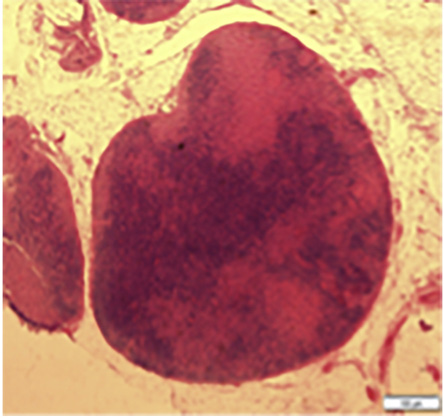

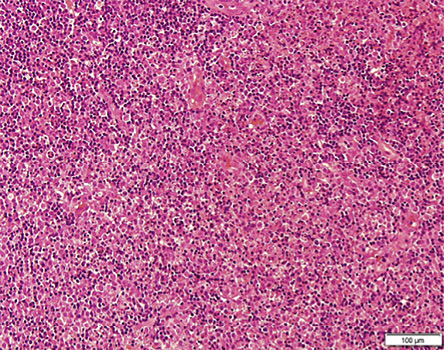

An excisional biopsy was carried out, and histopathological examination revealed histiocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, eosinophilic material, and abundant karyorrhectic debris, surrounding a central zone of overt necrosis, which was consistent with Kikuchi lymphadenitis [Figures 1 and 2]. Additionally, no granuloma, atypical cells, or malignancy were observed. Epstein-Barr was also ruled out by Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization. Her platelet count ranged between 80 and130 × 109/L. Considering the prevalence of malaria and tuberculosis in our region, screening for both conditions was done. On day 10 of admission, her white blood cell started to drop further with an absolute neutrophil count of 0.6. Peripheral blood film showed no atypical cells. In addition, her transaminitis was worsening, and she was evaluated for autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), which demonstrated positive AIH serology. Based on results of the connective tissue disease workup, namely antinuclear antibody with a homogenous pattern at a titre of 1:640, along with anti-Smith, anti-Ribosomal P, with low C3 levels, with leukopenia and arthralgia, the patient was diagnosed with SLE, meeting the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria. The elevated liver enzymes may have been part of SLE manifestation, lupoid hepatitis, AIH, or a manifestation of KFD. A definite confirmation requires further assessment, such as liver biopsy, which was not done in this case. By using simplified diagnostic criteria for AIH, the patient was classified as probable AIH without liver biopsy.

She was started on glucocorticoids therapy and hydroxychloroquine. She responded well following steroids initiation with improvement of symptoms. She was discharged with prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. Her final diagnosis was SLE associated with KFD and probable AIH. At a two-week post-discharge follow-up, the patient continued to improve clinically, with decreasing cervical lymphadenopathies and normalization of blood parameters [Table 2]. At three months after admission, she remained well with regression of lymph nodes, normal blood parameters, and resolution of other symptoms. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Figure 1: The lymph node is effaced with expanded interfollicular areas.

Figure 1: The lymph node is effaced with expanded interfollicular areas.

Figure 2: The interfollicular areas filled with histiocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, eosinophilic granular material, and abundant karyorrhectic debris.

Figure 2: The interfollicular areas filled with histiocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, eosinophilic granular material, and abundant karyorrhectic debris.

Discussion

KFD, also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, was first described in Japan by Kikuchi and Fujimoto in 1972.6 The association between KFD and SLE suggests a possible underlying autoimmune mechanism. Numerous reviews have observed frequent co-occurrence of KFD, either diagnosed concurrently with or after the SLE diagnosis.7 In this case, SLE developed alongside KFD as an initial presentation. KFD shares a similar sex and age predisposition with SLE, typically affecting young women age < 30 years.8 Although uncommon, KFD also been reported in association with other autoimmune conditions and manifestations such as AIH, antiphospholipid syndrome, polymyositis, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, bilateral uveitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and cutaneous necrotizing vasculitis.9,10

The exact cause of KDF is unknown; however, a few hypotheses suggest a possible viral trigger, given that the presentation is often flu-like symptoms. Possible viral association are Epstein-Barr Virus, Human Herpes 8, Human Herpes 6, HIV, parvovirus B19, and parainfluenza viruses.11,12 Diagnosing KDF can be challenging as it may mimic other diseases such as lymphoma, tuberculosis, viral lymphadenopathies, or even SLE lymphadenopathies. Patients often present with leukopenia, transaminitis, and elevated LDH as the initial presentation, which can overlap with other diseases. Although lymphadenopathy is a common presentation of SLE, it is not a criterion for SLE diagnosis. A lymph node histology in KDF may show areas of necrosis and the presence of histiocytes and T-cells, and may share similar histologic features with SLE. However, SLE-associated lymphadenopathy can be distinguished histologically from KFD by presence of hematoxylin bodies or lupus erythematosus cells, Azzopardi phenomenon, and abundance of plasma cells. Yu et al,13 retrospectively studied the clinical and pathological features and found that C4d deposition, which reflected autoantibody-mediated complement activation, was noted in SLE but not in KFD.

Conclusion

In this case, the presentation of cervical lymphadenopathies with constitutional symptoms, leukopenia, transaminitis, and elevated LDH and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, prompted extensive workup for malignancy and tuberculosis. It is essential to recognize KFD as a cause of cervical lymphadenopathy in young patients and its diagnosis should prompt further evaluation for autoimmune association especially SLE. Although KDF is infrequently encountered, it tends to be a self-limiting condition with favorable prognosis, emphasizing the importance of accurate diagnosis. It is essential to recognize this condition as it may be misinterpreted for other causes of lymphadenopathies and minimizes unnecessary laboratory investigations, misdiagnosis, and inappropriate treatment.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

reference

- 1. Ruaro B, Sulli A, Alessandri E, Fraternali-Orcioni G, Cutolo M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease associated with systemic lupus erythematous: difficult case report and literature review. Lupus 2014 Aug;23(9):939-944.

- 2. Payne JH, Evans M, Gerrard MP. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: a rare but important cause of lymphadenopathy. Acta Paediatr 2003;92(2):261-264.

- 3. Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, Oncul O, Yildirim S, Kaplan M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol 2007 Jan;26(1):50-54.

- 4. Yu SC, Huang HH, Chen CN, Chen TC, Yang TL. Blood cell and marrow changes in patients with Kikuchi disease. Haematologica 2022 Aug;107(8):1981-1985.

- 5. Abdel Hameed MR, Elbeih EA, Abd El-Aziz HM, Afifi OA, Khalaf LM, Ali Abu Rahma MZ, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and etiology of budd-chiari syndrome in upper Egypt. J Blood Med 2020 Dec;11:515-524.

- 6. Fujimoto Y, Kozima Y, Yamaguchi K. Cervical subacute lymphadenitis: a new clinicopathologic entity. Naika 1972;20:920-927.

- 7. Santana A, Lessa B, Galrão L, Lima I, Santiago M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 2005 Feb;24(1):60-63.

- 8. Sopeña B, Rivera A, Vázquez-Triñanes C, Fluiters E, González-Carreró J, del Pozo M, et al. Autoimmune manifestations of Kikuchi disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012;41(6):900-906.

- 9. Shusang V, Marelli L, Beynon H, Davies N, Patch D, Dhillon AP, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis associated with Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008 Jan;20(1):79-82.

- 10. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Miquel R, Campo E. Enigmatic Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Pathol 2004 Jul;122(1):141-152.

- 11. Rosado FG, Tang YW, Hasserjian RP, McClain CM, Wang B, Mosse CA. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol 2013 Feb;44(2):255-259.

- 12. Chong Y, Kang CS. Causative agents of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis): a meta-analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014 Nov;78(11):1890-1897.

- 13. Yu SC, Chang KC, Wang H, Li MF, Yang TL, Chen CN, et al. Distinguishing lupus lymphadenitis from Kikuchi disease based on clinicopathological features and C4d immunohistochemistry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60(3):1543-1552.