Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) comprises a group of clinical diseases, arising from abnormalities in the sinoatrial (SA) node system. This condition typically affects elderly individuals due to SA node degeneration. Although SSS is generally idiopathic, it can be both hereditary and acquired.1

Clinically, SSS appears as arrhythmias, including sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses or arrests, sinoatrial exit block, and alternating bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias.2 Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) has been theorized to cause SSS by affecting vagal discharge to the heart and disrupting the sinus cycle. However, age-related SA node degeneration remains the most common intrinsic cause of sinus node dysfunction (SND).2,3

Here, we present a case of SSS in a relatively young man with a rare underlying pathology and the resulting presentation.

Case Report

A 47-year-old man with unknown medical conditions presented to the emergency department with a four-day history of unprovoked syncope episodes, associated with nausea, somnolence, worsening headache, confusion, chest discomfort, and dizziness. The headache was generalized, persistent, progressive, severe, and was exacerbated in the recumbent position. It was not relieved by analgesics and did not vary in frequency or intensity throughout the day. The chest pain was mild, localized to the left side, and nonradiating. Neither aggravating nor alleviating factors were present, and there were no associated symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, or orthopnea. The patient denied similar previous symptoms, fever, chills, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, tinnitus, transient visual blurring on standing, or sensorimotor symptoms. His family history was noncontributory. He had no past medical history, was not on medications, and had a good socioeconomic standing.

Clinical examination revealed a blood pressure of 128/75 mmHg, a heart rate of 44 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 19 breaths/min, an afebrile status, and an oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. The patient was lying in bed, awake, oriented, and following commands. Fundoscopic examination revealed bilateral papilledema, mild left facial weakness, and left upper limb drift. The remainder of the neurological exam was unremarkable.

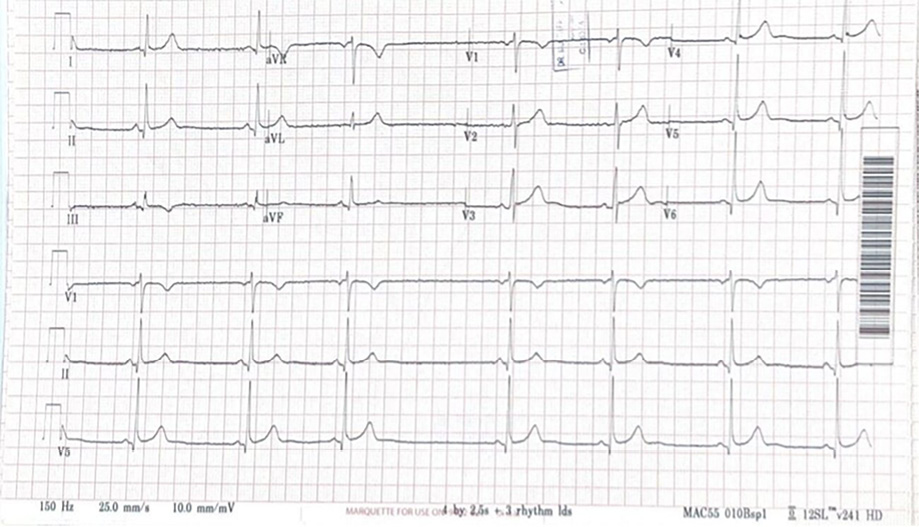

An electrocardiogram showed sinus bradycardia with multiple intermittent sinus pauses lasting 4–5 seconds [Figure 1].

Figure 1: The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus bradycardia with a heart rate of 40 beats/min, sinus arrhythmia, and sinoatrial (SA) exit block. The SA exit block results from the failure of pacemaker impulses to propagate beyond the SA node. The combination of these ECG abnormalities (sinus bradycardia, sinus arrhythmia, and associated dropped P waves) is consistent with sinus node dysfunction and sick

Figure 1: The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus bradycardia with a heart rate of 40 beats/min, sinus arrhythmia, and sinoatrial (SA) exit block. The SA exit block results from the failure of pacemaker impulses to propagate beyond the SA node. The combination of these ECG abnormalities (sinus bradycardia, sinus arrhythmia, and associated dropped P waves) is consistent with sinus node dysfunction and sick

sinus syndrome.

All blood tests, including the basic tests and those for vasculitis and thrombophilia, and spiral computed tomography (CT) of the chest, came back normal. A CT scan of the brain with and without contrast and CT cerebral venography revealed a picture consistent with extensive cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) [Figure 2].

Figure 2: (a) Non-enhanced axial CT of the brain revealed hyperdense transverse sinuses on the right side as well as edema in the right occipitoparietal regions. (b) An enhanced axial CT of the brain showed an empty delta sign due to thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus. The sign consists of a triangular area of enhancement with a low-attenuating center, which is the thrombosed sinus. (c) An axial CT venogram shows no flow in the right transverse and right sigmoid sinuses, with a filling defect due to thrombosis.

Figure 2: (a) Non-enhanced axial CT of the brain revealed hyperdense transverse sinuses on the right side as well as edema in the right occipitoparietal regions. (b) An enhanced axial CT of the brain showed an empty delta sign due to thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus. The sign consists of a triangular area of enhancement with a low-attenuating center, which is the thrombosed sinus. (c) An axial CT venogram shows no flow in the right transverse and right sigmoid sinuses, with a filling defect due to thrombosis.

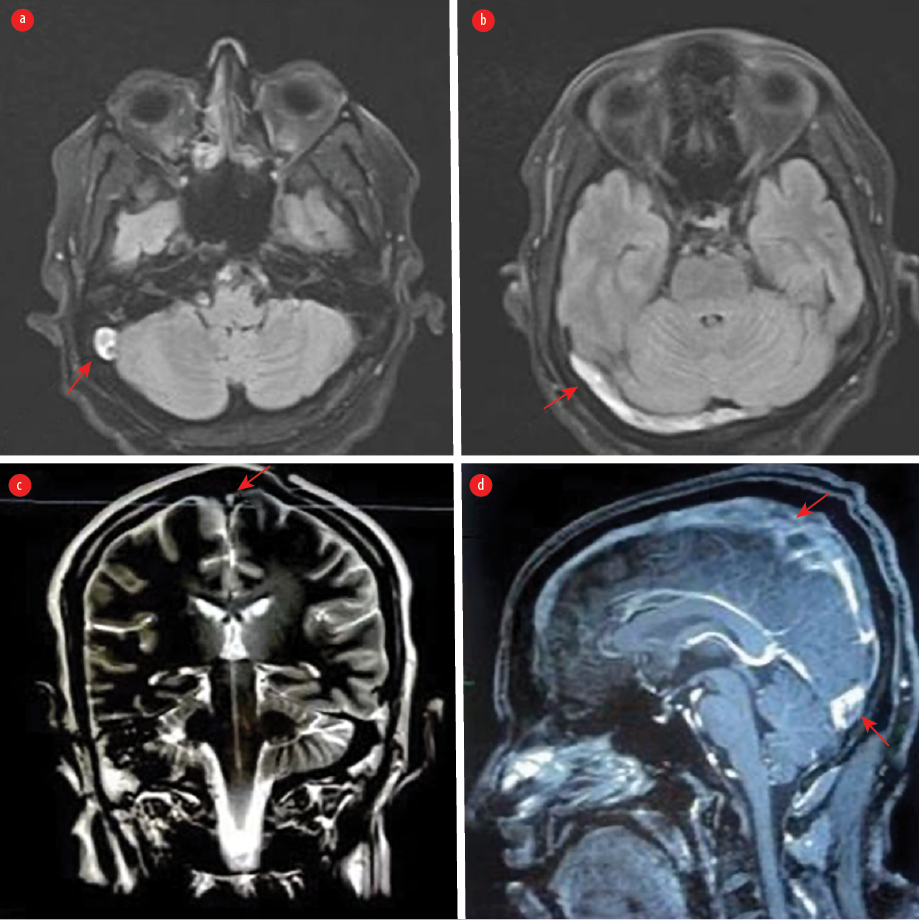

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated increased signal intensity in the right sigmoid sinus and right transverse sinus [Figure 3]. The echocardiogram was normal. Holter monitoring demonstrated sinus bradycardia. Therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated, and the patient recovered clinically despite continuing to experience mild headaches and dizziness. Cardiology evaluation revealed persistent symptomatic bradycardia with sinus bradycardia ranging from 30 to 45 beats/min with pauses lasting 4–5 seconds. After diagnosis of SSS, the patient was transferred to the cardiac care unit for pacemaker implantation. After 24 hours of observation, the post-procedure period was uneventful, and telemetry revealed sinus rhythm without a pacing beat. The recorded heart rate was within the normal range.

Figure 3: (a) An axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrates an area of abnormality with increased signal intensity in the right sigmoid sinus consistent with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). (b) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery weighted MRI demonstrates a hyperintense signal in the right transverse sinus. (c) A coronal T2-weighted MRI shows hypersignal intensity in the superior sagittal sinus. (d) A sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows filling defects along the superior sagittal sinus and involving the other cerebral sinuses, indicating extensive CVT.

Figure 3: (a) An axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrates an area of abnormality with increased signal intensity in the right sigmoid sinus consistent with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). (b) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery weighted MRI demonstrates a hyperintense signal in the right transverse sinus. (c) A coronal T2-weighted MRI shows hypersignal intensity in the superior sagittal sinus. (d) A sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows filling defects along the superior sagittal sinus and involving the other cerebral sinuses, indicating extensive CVT.

The patient was transferred to the acute stroke unit, where he remained for five days under the supervision of the neurology team following pacemaker implantation. Anticoagulation was resumed, and monitoring ensured neurological and cardiological stability before discharge. The absence of migraines and the disappearance of other symptoms indicated improvement. The patient was then instructed to follow-up in both the pacemaker and neurology clinics for further evaluation. Written consent was obtained from the patient.

Discussion

CVT is estimated to account for < 1% of all strokes. It primarily affects younger patients, with a female predominance, and presents with diverse clinical manifestations. Diagnosing CVT can be challenging without understanding its evolving epidemiology, clinical characteristics, associated conditions, and the neuroimaging findings required for confirmation.4

SSS, also known as SND, is a disorder of the SA node characterized by aberrant rhythms resulting from impaired pacemaker function and impulse transmission. These rhythms include atrial bradyarrhythmias, atrial tachyarrhythmias, and occasionally bradycardia alternating with tachycardia, known as tachy-brady syndrome,. These arrhythmias can lead to palpitations and tissue hypoperfusion, resulting in fatigue, dizziness, presyncope, and syncope.5

SSS is commonly associated with age-related degenerative fibrosis of the SA node, with an average age of onset around 68 years.6 Given the patient’s relatively young age, age-related degeneration is a less likely cause of SSS.7

Although a link between CVT and SSS is rare, a massive ICP elevation triggers the sympathoadrenal mechanism known as the Cushing response (CR). The CR manifests as hypertension, bradycardia, and respiratory irregularities.8

Various neurology and neurosurgical diseases, including stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, CVT, autoimmune diseases, tumors, infectious diseases, and certain medications and vaccines, have been implicated in elevating ICP and subsequently leading to SSS. In our patient, elevated ICP secondary to extensive CVT was the root cause of SSS. A study reported a case of glioblastoma in the right frontal nodule, corpus callosum, and right pontine area causing SSS that was attributed to an autonomic tone imbalance at the SA node, either due to hyperactivity of parasympathetic nerve outflow or hypoactivity of sympathetic nerve outflow.1 Arguija also reported a case of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis following an epidural injection in the cervical spine. The patient had a slow heart rate, which was thought to be caused by an increase in ICP due to CVT. The bradycardia resolved after she received acetazolamide.9 Furthermore, bradycardia was reported in patients with isolated intracranial hypertension syndrome with subsequent CVT.10 Additionally, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis caused a case of profound SND reported by Wong et al.11 A similar case of a 33-year-old Japanese woman with no significant medical history who presented with a picture of encephalitis and movement disorder was found to be positive for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor limbic encephalitis and exhibited sinus arrest lasting 9.28 seconds on telemetry.12 Ischemic stroke of the thalamus was also the culprit, where Asavaaree et al,13 reported a rare case of the artery of Percheron causing thalamic infarction that resulted in severe bradycardia.

It has also been documented that increased ICP brought on by a subarachnoid hemorrhage can impact the autonomic nervous system. According to Kawahara et al,14 the aberrant sinus cycle caused by the high ICP, which enhanced vagal discharge to the heart. Following intracranial hypertension, the classic definition of CR is the occurrence of hypertension, bradycardia, and apnea. This was evident in the case report of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage and CR, who self-aborted and had a good outcome.15 It was determined that sinus arrest during rapid eye movement sleep occurred due to a similar physiological process.16 Moreover, Blitz et al,17 reported intracranial complications of hypercoagulability and superinfection in the setting of COVID-19 in three cases, in which one developed bradycardia. Khan et al,18 reported a case of post-COVID-19 vaccine patients who developed cerebral venous sinus and ultimately bradycardia.

Brainstem lesions can produce autonomic and cardiovascular dysfunction. According to several case studies, lesions located within or near the medulla oblongata are the leading cause of compression of the vasomotor region.1 Brainstem compression is the mechanism by which both increased ICP and brainstem injuries result in autonomic dysfunction.19,20

Dadlani et al,21 highlighted the varied causes of coexisting bradycardia in neurosurgical patients and made the neurosurgical community aware of them. They reported a case of posterior fossa surgery in which persistent bradycardia developed in the postoperative period. They recommended that a very high degree of suspicion is essential for diagnosing SSS, as the patient would benefit from early medical management and possible external cardiac pacing in selected cases.

Hamaguchi et al,20 reported that the patient who had neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder with dorsal medulla and cervical cord lesions initially displayed area postrema syndrome (refractory nausea and vomiting) and potentially deadly bradycardia, ultimately requiring pacemaker insertion due to a diagnosis of SSS. In addition, SSS has also been reported shortly after taking the anesthetics fentanyl and vecuronium, which were known to trigger SSS.22 Our patient was notable because SSS could not have been caused by any other confounding factors.

Conclusion

SSS is a rare and serious cardiac rhythm disorder that can be caused by increased ICP. The association between SSS and CVT warrants further investigation. Early recognition and prompt treatment with pacemaker implantation are essential. Despite potential links, SSS and CVT are distinct medical conditions affecting different parts of the body with different underlying mechanisms. Further research is needed to fully understand any potential relationship, identify shared risk factors and optimize treatment strategies.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1. Makhaly S, Fallah P, Giannetti N. Elevated intracranial pressure as a cause of sick sinus syndrome. Case Rep Cardiol 2018 Jun;2018:5015840.

- 2. Semelka M, Gera J, Usman S. Sick sinus syndrome: a review. Am Fam Physician 2013 May;87(10):691-696.

- 3. Dakkak W, Doukky R. Sick sinus syndrome. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

- 4. Liberman AL. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2023 Apr;29(2):519-539.

- 5. De Ponti R, Marazzato J, Bagliani G, Leonelli FM, Padeletti L. Sick sinus syndrome. Card Electrophysiol Clin 2018 Jun;10(2):183-195.

- 6. Dobrzynski H, Boyett MR, Anderson RH. New insights into pacemaker activity: promoting understanding of sick sinus syndrome. Circulation 2007 Apr;115(14):1921-1932.

- 7. Devinsky O, Pacia S, Tatambhotla G. Bradycardia and asystole induced by partial seizures: a case report and literature review. Neurology 1997 Jun;48(6):1712-1714.

- 8. Schmidt EA, Despas F, Pavy-Le Traon A, Czosnyka Z, Pickard JD, Rahmouni K, et al. Intracranial pressure is a determinant of sympathetic activity. Front Physiol 2018 Feb;9:11.

- 9. Arguija AF. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis after cervical spine epidural injection. J Med Cases 2012;4(3):170-172.

- 10. Sikka G, Sharma D, Allen AV, Sobrinho CG, Kshetri R, Cano-Landivar J, et al. Rare case of isolated intracranial hyptertension syndrome (IIHS) with subsequent cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST). Chest 2015 Oct;148(4):270A.

- 11. Wong SW, Pang RY. Bradycardia in a woman presenting with altered behaviour. Acta Cardiol Sin 2023 Jan;39(1):177-180.

- 12. Chia PL, Tan K, Foo D. Profound sinus node dysfunction in anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor limbic encephalitis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2013 Mar;36(3):e90-e92.

- 13. Asavaaree C, Doyle C, Smithason S. Artery of Percheron infarction results in severe bradycardia: A case report. Surg Neurol Int 2018 Nov;9:230.

- 14. Kawahara E, Ikeda S, Miyahara Y, Kohno S. Role of autonomic nervous dysfunction in electrocardio-graphic abnormalities and cardiac injury in patients with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circ J 2003 Sep;67(9):753-756.

- 15. Wan WH, Ang BT, Wang E. The Cushing Response: a case for a review of its role as a physiological reflex. J Clin Neurosci 2008 Mar;15(3):223-228.

- 16. Coccagna G, Capucci A, Pierpaoli S. A case of sinus arrest and vagal overactivity during REM sleep. Clin Auton Res 1999 Jun;9(3):135-138.

- 17. Blitz SE, McMahon JT, Chalif JI, Jarvis CA, Segar DJ, Northam WT, et al. Intracranial complications of hypercoagulability and superinfection in the setting of COVID-19: illustrative cases. J Neurosurg Case Lessons 2022 May;3(21):CASE22127.

- 18. Khan S, Khalil M, Waqar Z. Post covid-19 vaccine (Sinovac) cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Pak J Neurol Sci 2022;17(2).

- 19. Nadkarni T, Kansal R, Goel A. Right cerebellar peduncle neurocysticercois presenting with bradycardia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010 Apr;152(4):731-732.

- 20. Hamaguchi M, Fujita H, Suzuki T, Suzuki K. Sick sinus syndrome as the initial manifestation of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a case report. BMC Neurol 2022 Feb;22(1):56.

- 21. Dadlani R, Challam K, Garg A, Hegde AS. Can bradycardia pose as a “red herring” in neurosurgery? Surgical stress exposes an asymptomatic sick sinus syndrome: Diagnostic and management dilemmas. Indian J Crit Care Med 2010 Oct;14(4):212-216.

- 22. Ishida R, Shido A, Kishimoto T, Sakura S, Saito Y. Prolonged cardiac arrest unveiled silent sick sinus syndrome during general and epidural anesthesia. J Anesth 2007;21(1):62-65.