Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata (LPD), also called disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis, is a rare benign gynecological disorder characterized by the dissemination of multiple smooth muscle nodules throughout the peritoneum. It was first described in 1952 by Wilson and Peale,1 and the term was coined by Taubert in 1965.2 The pathogenesis of LPD is poorly understood, and its management and prognosis have not been investigated adequately.

A meningioma is a tumor that forms in the meninges. An association between hormones and meningioma risk has been suggested, as it occurs in post-pubertal women twice as much as in men. The female-to-male ratio of meningioma patients rises to 3.15:1 during the peak reproductive years. The presence of estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors in some meningiomas also support a hormonal association.3,4 Other pointers include a tendency for the tumors to increase in size during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and exogenous hormones,5 and the regression of multiple meningiomas following cessation of estrogen and progesterone agonist therapy.

We present a rare case of association of LPD and meningioma in a female patient.

Case Report

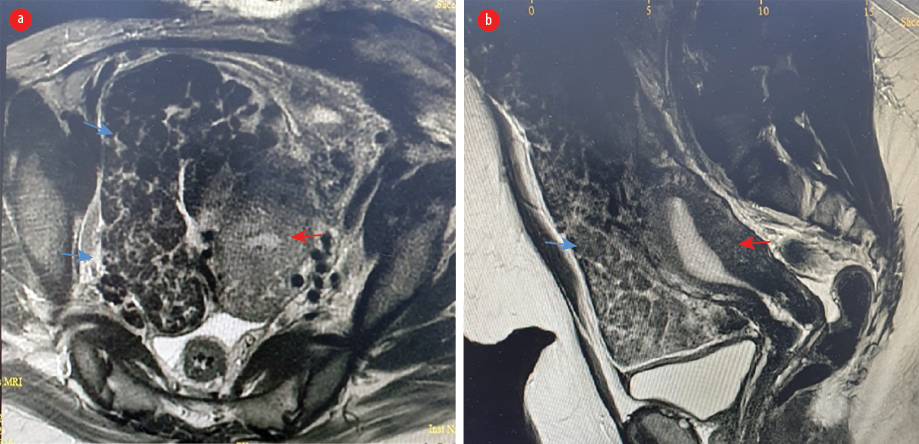

A 39-year-old multiparous woman underwent an emergency cesarean delivery after an antenatal cardiotocography revealed a fetal pathology. Biopsy from the peritoneal mass confirmed a diagnosis of LPD. The exact diagnosis had been made five years earlier by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [Figure 1], for which she had refused further evaluation or treatment. The patient had no other significant medical or surgical history.

Figure 1: MRI of abdomen using gadolinium-based contrast media. (a) Axial view. (b) Sagittal view (red arrow: uterus; blue arrow: leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata).

Figure 1: MRI of abdomen using gadolinium-based contrast media. (a) Axial view. (b) Sagittal view (red arrow: uterus; blue arrow: leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata).

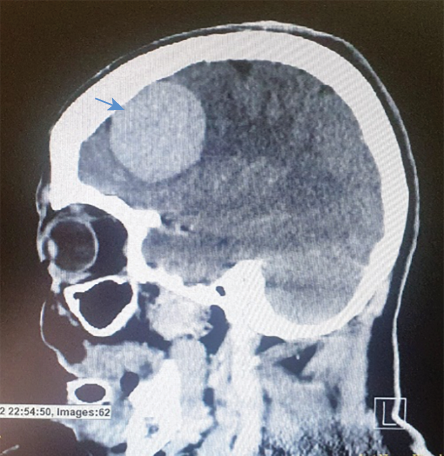

Six days after the cesarean section, the patient developed status epilepticus and was admitted to the intensive care unit with inotropic support, under the care of a multidisciplinary team comprising intensive care unit anesthetists, an obstetrician, a neurosurgeon, a general physician, and a gynecologic oncologist. Her electroencephalogram revealed focal epileptiform activity in the right fronto-temporo-parietal region for which she was put on antiepileptic medications. Computed tomography (CT) brain angiography [Figure 2] and MRI brain with gadolinium revealed a right frontal meningioma, but an immediate intervention was ruled out in view of her critical condition. She developed a fever, and a swab culture from the cesarean skin wound showed growth of Escherichia coli with extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Her initial aerobic and anerobic blood cultures, high vaginal swab, and urine culture showed no growth. Sputum culture revealed scanty growth of multidrug-resistant organism Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Tests yielded negative for Brucellae, Coxiella burnetii, tuberculosis pathogen, TORCH pathogens, HIV, and other viral and fungal pathogens. CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed left lung consolidation/collapse without pleural effusion. Mild ascites was present. One week later, repeat CT revealed left lung consolidation/collapse in addition to left pleural effusion, with no obvious pulmonary embolism. The ascites was increasing. The ultrasound image of the chest revealed moderate left-sided pleural effusion with atelectatic left lower lobe. Echocardiography was normal.

Figure 2: CT scan of sagittal view of the brain showing the meningioma.

Figure 2: CT scan of sagittal view of the brain showing the meningioma.

Despite receiving on multiple parenteral antibiotics, the patient remained febrile with increasing inflammatory markers. The ascites had resulted in abdominal distension; ascitic tapping was done under ultrasound guidance. No bacterial growth was detected in the ascitic fluid.

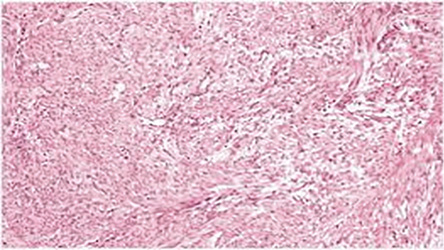

With no improvement in the clinical condition of the patient and increasing ascites, we proceeded with excision of the tumor and total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy under ventilator support. The excised uterus had the size of 12 weeks gestation, and the subserosal fibroid had extended into the entire peritoneum, bladder serosa, and omentum. The mass weighed 8 kg. Ascitic fluid culture and sensitivity showed no growth. Histopathology showed diffuse benign leiomyomatosis with signs of degeneration, with no evidence of infection or atypia [Figures 3 and 4]. An intraperitoneal drain was placed.

Figure 3: Hysterectomy specimen with the peritoneal leiomyomatosis involving peritoneum

Figure 3: Hysterectomy specimen with the peritoneal leiomyomatosis involving peritoneum

and omentum.

Figure 4: Histopathology: diffuse benign leiomyomatosis with signs of degeneration, with no evidence of infection or atypia, magnification = 40 ×.

Figure 4: Histopathology: diffuse benign leiomyomatosis with signs of degeneration, with no evidence of infection or atypia, magnification = 40 ×.

Postoperatively, there was an initial lowering in the fever and inflammatory markers, but they rose again later. The patient could not be extubated as she was on inotropic support. CT scans of the abdomen, pelvis, and chest conducted on postoperative day 7 showed a newly developed pelvic abscess collection with air. Electroencephalogram revealed intermittent right frontotemporal parietal epileptiform discharges. Repeat CT of the brain revealed a stable right frontal extraaxial lesion representing meningioma with no evidence of abnormal meningeal enhancement. The abscess in the pelvis was drained under CT guidance, and its culture revealed scanty growth of multidrug-resistant organism carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia.

On postoperative day 10, the patient had high-grade fever, hypotension on high inotropic support, and suffered cardiac arrest. She was revived by cardiopulmonary resuscitation. ABG revealed metabolic acidosis (pH 6.9), high potassium, and lactate, which were corrected. The patient had another cardiac arrest. Though cardiopulmonary resuscitation was given as per advanced cardiovascular life support protocol, she could not be revived. Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s husband.

Discussion

LPD could be caused by metaplasia of mesenchymal cells of the peritoneum, and, in susceptible women, residual myoma in the abdominal cavity postoperatively might contribute to its development.6,7 Metaplasia and differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells into smooth muscle cells may be promoted by estrogen exposure.8 Therefore, LPD is often considered a benign premenopausal disease. An association between multiple intracranial meningioma presentations and long-standing use of megestrol acetate, a progesterone agonist, was confirmed histologically by the presence of progesterone receptors in the largest tumor. Regression of the tumor was noted with discontinuation of the medication.8 Studies have shown a stronger association with progesterone receptor (PR) status than with estrogen receptor (ER) status.3

The PR status was associated with changes near the NF2 gene on 22q, suggesting that hormones likely play an important role in the development or progression of some meningiomas.3 The predominance of meningiomas in females and their accelerated growth during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle have led to several studies examining the potential role of steroids in meningioma growth. The presence of ER-α and ER-β on meningiomas was identified using reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction Southern blot analysis.4 A retrospective cohort study found women with uterine myoma to be at a significantly higher risk of developing meningioma (45%) than those without uterine myoma.9 The expression of the PR alone in meningiomas signals a favorable clinical and biological outcome. In female patients, sex hormone receptor status should routinely be studied for its prognostic value and should be considered in tumor grading. The initial receptor status of a tumor may change with the tumor progression or recurrence.10

Intracranial leiomyoma may present as a primary or secondary presentation. Various cases of intracranial leiomyoma have been confirmed based on histology, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy.11,12 Alessi et al,13 reported cases of benign metastasizing leiomyoma to skull base and spine.

Conclusion

MRI can establish the definitive diagnosis of diffuse leiomyomatosis with a high degree of confidence. Meningioma is rarely associated with leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata, as in the current case. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Management by a multidisciplinary team is recommended.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1. Willson JR, Peale AR. Multiple peritoneal leiomyomas associated with a granulosa-cell tumor of the ovary. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1952 Jul;64(1):204-208.

- 2. Taubert HD, Wissner SE, Haskins AL. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata; an unusual complication of genital leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol 1965 Apr;25:561-574.

- 3. Claus EB, Park PJ, Carroll R, Chan J, Black PM. Specific genes expressed in association with progesterone receptors in meningioma. Cancer Res 2008 Jan;68(1):314-322.

- 4. Carroll RS, Zhang J, Black PM. Expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in human meningiomas. J Neurooncol 1999 Apr;42(2):109-116.

- 5. Jhawar BS, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Sex steroid hormone exposures and risk for meningioma. J Neurosurg 2003 Nov;99(5):848-853.

- 6. Al-Talib A, Tulandi T. Pathophysiology and possible iatrogenic cause of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2010;69(4):239-244.

- 7. Lu B, Xu J, Pan Z. Iatrogenic parasitic leiomyoma and leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata following uterine morcellation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2016 Aug;42(8):990-999.

- 8. Vadivelu S, Sharer L, Schulder M. Regression of multiple intracranial meningiomas after cessation of long-term progesterone agonist therapy. J Neurosurg 2010 May;112(5):920-924.

- 9. Yen YS, Sun LM, Lin CL, Chang SN, Sung FC, Kao CH. Higher risk for meningioma in women with uterine myoma: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Neurosurg 2014 Mar;120(3):655-661.

- 10. Pravdenkova S, Al-Mefty O, Sawyer J, Husain M. Progesterone and estrogen receptors: opposing prognostic indicators in meningiomas. J Neurosurg 2006 Aug;105(2):163-173.

- 11. Kroe DJ, Hudgins WR, Simmons JC, Blackwell CF. Primary intrasellar leiomyoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 1968 Aug;29(2):189-191.

- 12. Yaltırık CK, Yamaner EO, Harput MV, Sav MA, Türe U. Primary intracranial intraventricular leiomyoma: a literature review. Neurosurg Rev 2021 Apr;44(2):679-686.

- 13. Alessi G, Lemmerling M, Vereecken L, De Waele L. Benign metastasizing leiomyoma to skull base and spine: a report of two cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2003 Jul;105(3):170-174.