Preeclampsia is a disease of placenta, responsible for the annual death of approximately 30 000 women1 and 500 000 infants worldwide.2,3 It is defined as new-onset hypertension (≥ 140/90 mmHg) after 20 weeks of gestation in a previously normotensive woman, accompanied by proteinuria (≥ 300 mg/24h, protein/creatinine ratio ≥ 0.3, or dipstick ≥ 1+) or evidence of end-organ dysfunction.2

Preeclampsia is a multiorgan disorder with end-organ involvement, including thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100 000/µL), renal insufficiency (serum creatinine > 1.1 mg/dL or doubling of baseline), elevated liver enzymes (≥ 2× upper limit of normal) with or without severe epigastric pain, pulmonary edema, or persistent neurological symptoms such as headache or visual disturbances.4 Severe disease can lead to maternal seizures, intracranial hemorrhage, and death of the mother and fetus and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in middle- and low-income countries.5 In Pakistan, about 34% percent of maternal deaths are attributed to complications related to preeclampsia.6

Delivery is the definitive treatment for preeclampsia. However, determining the timing of delivery can be challenging, considering the often-conflicting maternal and neonatal outcomes. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends expectant management till 37 weeks of gestation, with close maternal and fetal surveillance using clinical, biochemical, and hematological markers.4 However, delivery is indicated in cases of severe preeclampsia or signs of impending eclampsia, regardless of

gestational age.

Eclampsia-related preterm births7 account for about 25–30% of all preterm deliveries.8,9 The burden is higher in developing countries with limited resources, leading to higher rates of maternal and perinatal mortality.10 Healthcare providers in low-resource settings face a difficult trade-off between early delivery and the risk of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

The present study was conducted at the Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, a 659-bedded private sector teaching hospital that receives referrals from a wide catchment area encompassing the city and surrounding regions. During our three-year study period, Aga Khan University Hospital conducted a total of 16 229 deliveries, averaging approximately 5400 per year. The mean prevalence of preeclampsia during this period was around 6.7% as per our departmental statistics.

Our study aimed to evaluate the maternal and perinatal outcomes of preeclampsia in the above population. Its findings will assist obstetricians to use locally relevant data for counseling expectant parents, and inform policymakers to develop local and national referral protocols and resource allocation strategies.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January 2017 to December 2019 at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi. We included all pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia between 24+0 and 36+6 weeks of gestation. Women with fetal anomalies or incomplete medical records were excluded.

Participants were classified according to the WHO prematurity classification: group I: extremely preterm birth (EPB): 24–27+6 weeks of gestation; group II: very preterm birth (VPB): 28–31+6 weeks; group III: moderate to late preterm birth (MLPB): 32–36+6 weeks. Demographic data of the mothers and newborns were collected from the hospital medical records, the labor room management system, and the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

The following outcome data were collected: gestational week at delivery, mode of delivery, maternal complications (e.g., eclampsia, stroke, pulmonary edema, abruptio placenta, maternal mortality, etc.), fetal growth restriction (FGR), newborn birth weight, Apgar score, NICU admission, neonatal death, and intrauterine death (IUD).

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 19.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). Numeric variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median with IQR. Categorical data were reported as proportions and percentages. Continuous variables were evaluated using visual (histograms) and analytical (Shapiro-Wilks test) methods. Normally distributed data were assessed using one-way analysis of variance. Kruskal-Wallis’s test and Mann-Whitney U test compared non-normally distributed metric data. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical data. Variables with p < 0.20 in the univariate analysis were subjected to a multivariable model to explore independent risk factors. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine independent predictors for EPB and VPB. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Ethical Review Committee of Aga Khan University evaluated the study proposal (Ref. No. 2020-3531-11013 dated 2 July 2020). It waived the need for ethical permission in view of its retrospective nature and the lack of direct patient involvement. All data were maintained with strict confidentiality and no personally identifiable information was collected.

Results

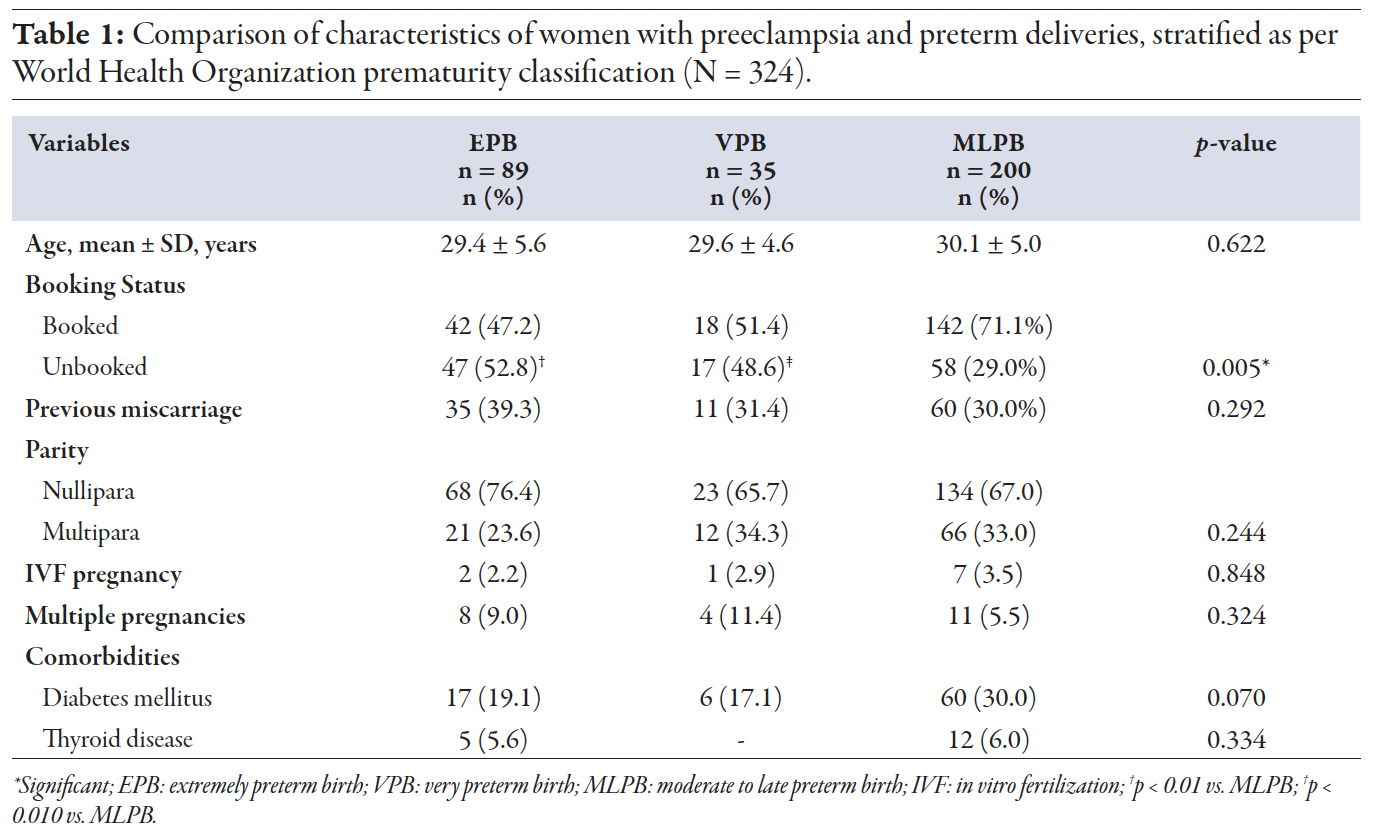

The participants comprised 324 women with preeclampsia, with mean age of 29.8 ± 5.1 years and who delivered between 24 and 36+6 weeks of gestation. Among them, 202 (62.3%) were booked, and 225 (69.4%) were primiparous. About one third (106; 32.7%) had a history of miscarriage and 23 (7.1%) had multiple gestations. The mean age, history of miscarriage, parity, and multiple pregnancies were not statistically significant across the groups. Ten (3.1%) women conceived through in vitro fertilization, with no significant difference among the groups (p = 0.848). The rate of unbooked cases was significantly higher in EPB as compared to MLPB (p < 0.010). The most common maternal comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (25.6%) and thyroid disease (5.2%) [Table 1].

Table 1

Table 1

Most 285 (87.9%) women underwent cesarean sections, while a minority (39; 12.0%) had vaginal deliveries, resulting in 331 neonates, including twins and triplets. Based on gestational age at delivery, women were classified into EPB = 89 women (27.5%; 91 neonates); VPB = 35 women (10.8%; 39 neonates); MLPB = 200 women (61.7%; 201

neonates) [Table 2].

Table 2

Table 2

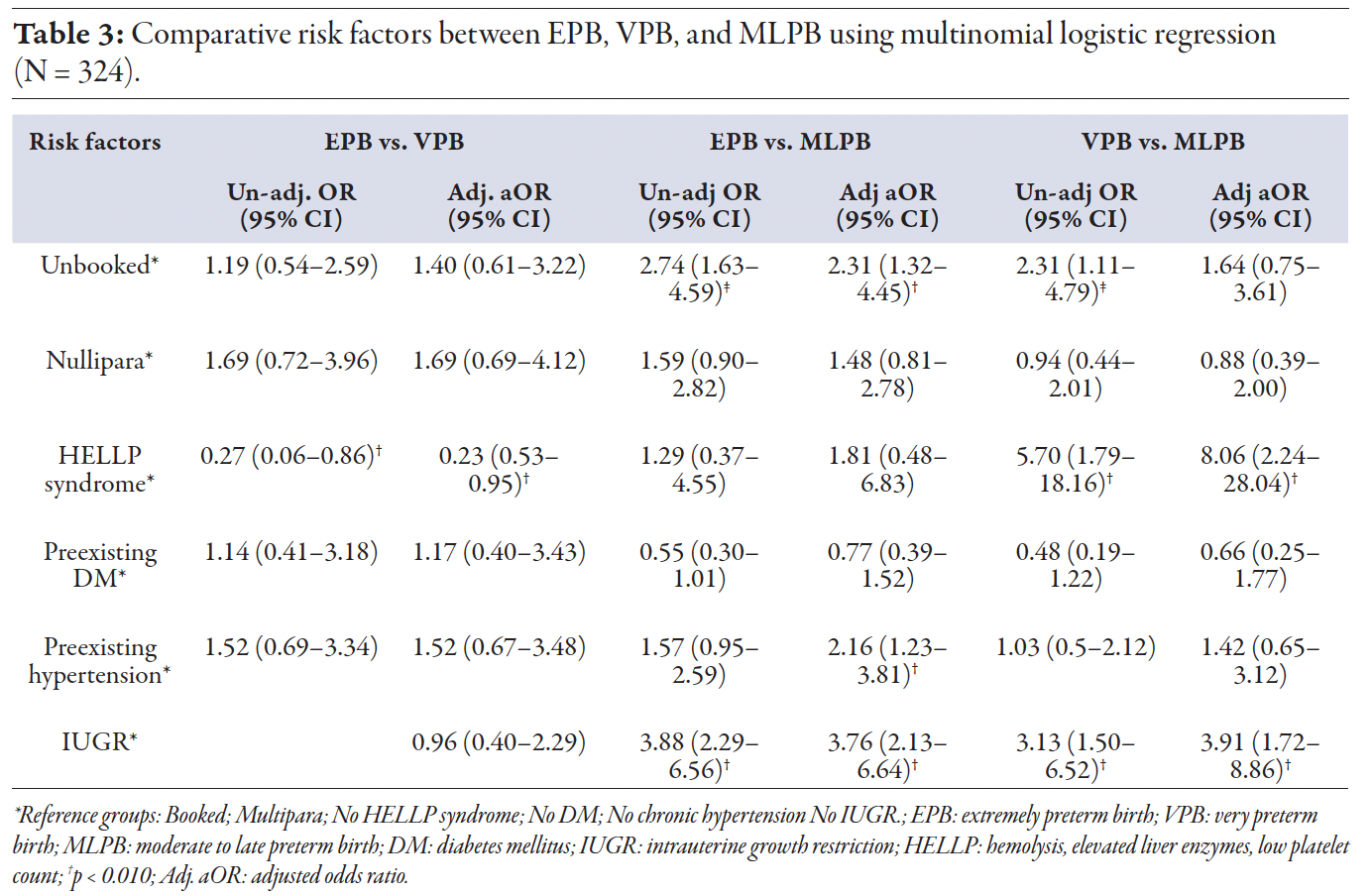

Table 2 compares maternal characteristics and complications between the groups. FGR-intrauterine growth restriction was diagnosed in 127 (39.2%) participants. The rate of intrauterine growth restriction was significantly higher in women with EPB (59.6% vs. 27.5%; p < 0.01) and VPB (54.3% vs. 27.5%; p < 0.01) as compared to MLPB, with no significant difference between EPB and VPB. A total of 45 (13.9%) women developed serious maternal complications, including eclampsia, pulmonary edema, abruptio placenta, postpartum hemorrhage, and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome. The overall rate of complications was significantly higher in the VPB group than in the MLPB group (31.4% vs. 10.0%; p < 0.010). HELLP syndrome was significantly more prevalent in the VPB group than in the EPB (17.1% vs. 3.5%; p < 0.010) and MLPB (17.1% vs. 4.5%; p < 0.010). IUD occurred in 18 (5.6%) cases with no significant differences across groups. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for independent risk factors were investigated using multinomial logistic regression analysis. HELLP syndrome was the most critical risk factor in the VPB group. IUD was identified as a significant risk factor in EPB and VPB compared to MLPB in univariate and multivariate analyses after controlling the effect of booking status, parity, HELLP syndrome, diabetes, and preexisting hypertension [Table 3].

Table 3

Table 3

Intergroup comparison of neonatal outcomes is presented in Table 4. The median birth weight was significantly lower in the EPB and VPB groups compared to the MLPB group. The rate of very low birth weight (≤ 1.5 kg) was significantly higher in EPB than in MLPB (89.0% vs. 12.9%; p < 0.01) and in VPB than in MLPB (76.9% vs. 12.9%; p < 0.01). The need for ventilatory support and Apgar score < 7 were significantly greater in the EPB compared to VPB and MLPB groups. Among 331 neonates, 21 (6.3%) died, with mortality rates significantly higher in the EPB group compared to VPB and MLPB.

Table 4

Table 4

Discussion

Our study revealed a high incidence of maternal complications, particularly in the EPB and VPB groups. The VPB group experienced twice the complication rate of EPB group and three times that of MLPB group. This suggests that early-onset preeclampsia (before 34 weeks) carries significantly greater risk of complications. These findings are consistent with prior studies showing that early-onset preeclampsia has a worse prognosis compared to the late-onset variant (34–37 weeks).11,12 This is also supported by a systematic review by Guida et al.13

Although both EPB and VPB groups had higher incidence of early-onset preeclampsia, the VPB group showed twice the rate of maternal complications. This apparent paradox likely reflects a more interventionist approach in the EPB group, where gestational age < 28 weeks shifts the priority to maternal well-being due to the poor fetal prognosis.4 After 28 weeks, the priority changes to prolonging pregnancy to improve fetal survival, unless maternal or perinatal risk becomes imminent.4 Pakistan’s high maternal mortality rate (186 per 100 000 live births) may further contribute to the risk.14 Perinatal outcomes are also poorer than in other low and middle-income countries, with a neonatal mortality rate of 41 per 1000 live births.15, 16

However, this pattern is not unique to Pakistan or the developing world.16 A systematic review by G. Scott et al,17 recommended early delivery in cases of severe preeclampsia, irrespective of gestational age.For late-onset preterm preeclampsia, there is clear evidence supporting planned preterm delivery to prevent severe maternal morbidity.18 Our data align with previous studies showing that preeclampsia causes severe organ dysfunction, highlighting the fact that no form of this condition is benign.11

Half of the women in both EPB and VPB were un-booked referrals, whereas 71.0% of MLPB cases were booked—likely because more complicated cases were referred for advanced care of the mother and baby from primary and secondary centers. Studies show that the interval between diagnosis and delivery in preeclampsia is usually brief, even among women with less severe symptoms managed expectantly.19 In such situations, delays in transferring patients should be avoided. 19

There is limited guidance regarding the mode of delivery in preterm preeclampsia. In our study, 88.0% of women delivered by cesarean section, with no significant differences across the three groups. This contrasts with term preeclampsia, where vaginal delivery is typically preferred.20 When preterm birth is indicated, many opt for cesarean section due to the severity of maternal conditions, prolonged induction times, and concerns about fetal tolerance during labor.21 Similarly, a study on Chinese women with severe preeclampsia reported a very high rate (84.9%) of cesarean delivery athough most cases were term deliveries.22,23 However, a study in the USA reported that nearly half of women with preterm preeclampsia delivered vaginally after induction of labor, with comparatively low maternal morbidities and better neonatal outcomes, suggestive of higher quality

of care.24

More than half of the pregnancies in our EPB and VPB groups experienced complications, compared over one-quarter in the MLPB group. FGR was the most prevalent complication observed. Other researchers have also reported a strong association between FGR and severe and early-onset preeclampsia, attributable to the common pathophysiology of FGR and early-onset preeclampsia.25–27 This has led some researchers to propose including FGR among the diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia as a form of organ dysfunction.28 Our results show the rate of FGR to be almost double in the EPB and VPB groups compared to the MLPB group, supporting the hypothesis that preeclampsia has different subtypes based on etiology—one associated with placental dysfunction and FGR, and another with normal or enhanced placental function.29

We found that neonatal outcomes depended primarily on gestational age at delivery and were mainly prematurity-related. Significant differences were observed across the groups in weight at birth, NICU admission, and the requirement for ventilatory support. The rate of neonatal death was highest in the EPB group. Among women who delivered after 28 weeks of gestation of gestation, only one neonatal death

was reported.

These findings support the use of expectant management in extreme preterm pregnancies. After 28 weeks, if maternal condition warrants delivery, favorable neonatal survival rates can be expected. A multicenter randomized controlled trial in Latin America on severe preeclampsia after 28 weeks of gestation found that conservative management did not improve perinatal mortality or other morbidities, supporting our findings.30 International guidelines support expectant management of preeclampsia up to at least 34 weeks, with vigilant monitoring to improve neonatal outcomes.13 In low- and middle-income countries, limited resources and complex cultural and social barriers often result in late diagnoses of preeclampsia.31 If optimal expectant management is not feasible, prompt delivery should be considered for maternal safety.

A key strength of this study is that it is the first among low- and middle-income countries to evaluate maternal and perinatal outcomes of preeclampsia based on the WHO classification of prematurity. This provides valuable insights into neonatal outcomes within a well-equipped NICU and timely highlights the importance of early referrals. The findings highlight the potential for improved neonatal survival with access to specialized care.

However, the study has limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevents determining causal relationships. Second, the lack of data on unbooked cases limits assessment of the impact of pre-existing hypertension on the onset and progression of preeclampsia. Third, as a single-center study conducted in Southern Pakistan, the results may not be generalizable to the entire country. Moreover, data from a well-equipped private healthcare setting may not reflect conditions in public sector hospitals, which serve the majority of the population.

Conclusion

Preeclampsia is a serious complication in pregnancy with significant risks to both mother and fetus. After diagnosis of preterm preeclampsia, the only reason to prolong the pregnancy is to enhance neonatal outcomes. Our findings suggest that neonatal mortality is high when delivery occurs before 28 weeks of gestation, requiring expectant management to improve neonatal outcomes. Maternal complications are higher with early-onset preeclampsia (< 32 weeks). Prioritizing early delivery based on maternal condition after 28 weeks, followed by NICU management of the neonate, can enhance both maternal and neonatal outcomes. Our study also highlights the need for timely decision-making in the context of available neonatal care resources.

Future research should adopt prospective multicenter designs to thoroughly explore confounding factors and enhance the generalizability of findings related to maternal and perinatal outcomes in preeclampsia. We also encourage our counterparts in the developing world, especially in South Asia, to conduct research and share scientific insights for collective advancement.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2014 Sep;384(9947):980-1004.

- 2. von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Pre-eclampsia: an update. Curr Hypertens Rep 2014 Aug;16(8):454.

- 3. von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Preventing deaths due to the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016 Oct;36:83-102.

- 4. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 8] Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548335.

- 5. Muhammad N, Liaqat N. Causes and outcome of pregnancy related acute kidney injury. Pak J Med Sci 2024;40(1Part-I):64-67.

- 6. Soomro S, Kumar R, Lakhan H, Shaukat F. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia disorders in tertiary care center in Sukkur, Pakistan. Cureus 2019 Nov;11(11):e6115.

- 7. Jayaram A, Collier CH, Martin JN. Preterm parturition and pre-eclampsia: the confluence of two great gestational syndromes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020 Jul;150(1):10-16.

- 8. Behrman RE. Institute of medicine (US) committee on understanding premature birth and assuring healthy outcomes. In: Behrman RE, Butler AS, editors. Preterm birth causes, consequences, and prevention. National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA; 2007.

- 9. Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM, Vintzileos AM. Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006 Dec;19(12):773-782.

- 10. Omer S, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. The influence of social and cultural practices on maternal mortality: a qualitative study from South Punjab, Pakistan. Reprod Health 2021 May;18(1):97.

- 11. Pettit F, Mangos G, Davis G, Henry A, Brown MA. Pre-eclampsia causes adverse maternal outcomes across the gestational spectrum. Pregnancy Hypertens 2015 Apr;5(2):198-204.

- 12. Lisonkova S, Sabr Y, Mayer C, Young C, Skoll A, Joseph KS. Maternal morbidity associated with early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2014 Oct;124(4):771-781.

- 13. Guida JP, Surita FG, Parpinelli MA, Costa ML. Preterm preeclampsia and timing of delivery: a systematic literature review. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2017 Nov;39(11):622-631.

- 14. Midhet F, Khalid SN, Baqai S, Khan SA. Trends in the levels, causes, and risk factors of maternal mortality in Pakistan: a comparative analysis of national surveys of 2007 and 2019. PLoS One 2025 Jan 13;20(1):e0311730.

- 15. Aziz A, Saleem S, Nolen TL, Pradhan NA, McClure EM, Jessani S, et al. Why are the Pakistani maternal, fetal and newborn outcomes so poor compared to other low and middle-income countries? Reprod Health 2020 Dec;17(Suppl 3):190.

- 16. Memon Z, Fridman D, Soofi S, Ahmed W, Muhammad S, Rizvi A, et al. Predictors and disparities in neonatal and under 5 mortality in rural Pakistan: cross sectional analysis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 2023 Jun;15:100231.

- 17. Scott G, Gillon TE, Pels A, von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Guidelines-similarities and dissimilarities: a systematic review of international clinical practice guidelines for pregnancy hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022 Feb;226(2S):S1222-S1236.

- 18. Chappell LC, Brocklehurst P, Green ME, Hunter R, Hardy P, Juszczak E, et al; PHOENIX Study Group. Planned early delivery or expectant management for late preterm pre-eclampsia (PHOENIX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019 Sep;394(10204):1181-1190.

- 19. McKinney D, Boyd H, Langager A, Oswald M, Pfister A, Warshak CR. The impact of fetal growth restriction on latency in the setting of expectant management of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016 Mar;214(3):395.e1-e7.

- 20. Koopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, Vijgen SM, Aarnoudse JG, Bekedam DJ, et al; HYPITAT study group. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks’ gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009 Sep;374(9694):979-988.

- 21. Kuper SG, Sievert RA, Steele R, Biggio JR, Tita AT, Harper LM. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in indicated preterm births based on the intended mode of delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2017 Nov;130(5):1143-1151.

- 22. Wu SW, Zhang WY. Effects of modes and timings of delivery on feto-maternal outcomes in women with severe preeclampsia: a multi-center survey in mainland China. Int J Gen Med. 2021 Dec 14;14:9681-9687

- 23. Amorim MM, Katz L, Barros AS, Almeida TS, Souza AS, Faúndes A. Maternal outcomes according to mode of delivery in women with severe preeclampsia: a cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015 Apr;28(6):654-660.

- 24. Coviello EM, Iqbal SN, Grantz KL, Huang C-C, Landy HJ, Reddy UM. Early preterm preeclampsia outcomes by intended mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019 Jan;220(1):100.e1-100.e9.

- 25. Odegård RA, Vatten LJ, Nilsen ST, Salvesen KÅ, Austgulen R. Preeclampsia and fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 2000 Dec;96(6):950-955.

- 26. Ness RB, Sibai BM. Shared and disparate components of the pathophysiologies of fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006 Jul;195(1):40-49.

- 27. Lyall F, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Spiral artery remodeling and trophoblast invasion in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: relationship to clinical outcome. Hypertension 2013 Dec;62(6):1046-1054.

- 28. Obata S, Toda M, Tochio A, Hoshino A, Miyagi E, Aoki S. Fetal growth restriction as a diagnostic criterion for preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 2020 Jul;21:58-62.

- 29. Rasmussen S, Irgens LM. Fetal growth and body proportion in preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2003 Mar;101(3):575-583.

- 30. Vigil-De Gracia P, Tejada OR, Miñaca AC, Tellez G, Chon VY, Herrarte E, et al. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: the MEXPRE Latin Study, a randomized, multicenter clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013 Nov;209(5):425.e1-e8.

- 31. Ghulmiyyah L, Sibai B. Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Semin Perinatol 2012 Feb;36(1):56-59.