Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a widespread neurodevelopmental condition that persists into adulthood, correcting the traditional perception of it as solely a childhood disorder.1 Adult ADHD presents unique challenges due to its varied clinical presentations, coexisting psychiatric comorbidities, and impact on

daily functioning.1

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2001 to 2019 covering 40 studies from 30 countries, estimated an adult ADHD prevalence of approximately 6.8%, representing 366.3 million adults globally.2 Another study based on the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey reported a prevalence of 2.8% in a sample of

26 744 adults.3

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), a systematic review and meta-analysis by Al-Wardat et al,4 found a surprisingly high adult ADHD prevalence of 13.5%— even higher than the 10.1% in children and adolescents in the region. The authors suggested that this may be due to methodological differences, but such an unusual finding underlines the need for further research on adult ADHD in the MENA region.

Oman, a Gulf Cooperation Council member state in the MENA region, has a population of about 5 million, of whom roughly 2.2 million are Omani nationals. Bedawi et al,5 recently analyzed 39 881 adult outpatients visiting a major referral hospital in Musat over five years, and found an ADHD prevalence of 1.8%, significantly lower than reported by Al-Wardat et al,4 for the MENA region. This suggests that more detailed research is required to establish the prevalence of adult ADHD in the region, including Oman.

This typically involves pharmacological interventions, usually central nervous system stimulants (methylphenidate, amphetamines) or non-stimulant selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as atomoxetine. Response to these medications varies significantly across individuals, further complicating management. Mészáros et al,6 conducted a meta-analysis of 11 double-blind clinical trials with parallel-group designs (n = 1991). They found that active medications significantly improved ADHD symptoms compared to placebo, with a standardized mean difference of 0.43 and a 95% CI of 0.24–0.62. A recent meta-analysis from Radonjic et al,7 revealed that non-stimulant drugs such as atomoxetine were more effective in treating ADHD in adults than placebo. However, the placebo had better acceptability and tolerability. Cortese et al,8 in a systematic review and network meta-analysis, found the most recommended ADHD medications to be methylphenidate for children and adolescents, and amphetamines for adults.

The above reviews have focused mainly on studies in industrialized countries of the Global North. Countries of the Global South—particularly those with different genetic, epigenetic, and cultural backgrounds like Oman—remain underrepresented. With most drugs being developed in the global north and their safety trials conducted in Western populations, there is a limited understanding of accurate pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profiles in non-Western ethnicities and cultures. Sentinel studies are needed to examine outcomes and predictors of adult ADHD treatment with atomoxetine and methylphenidate in countries such as Oman, laying the groundwork for future interventions incorporating genetic and epigenetic factors.

In Oman, the typical first-line pharmacotherapies to treat adult ADHD are methylphenidate and atomoxetine.5 This study addresses knowledge gaps in clinical presentation, treatment outcomes, and predictors of response of adult Omanis newly diagnosed with ADHD and routinely treated with atomoxetine and methylphenidate, through naturalistic observation.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted among consecutive attendees at the psychiatric clinic of Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman, a public sector institution where healthcare services are provided free for Omani citizens. This is also the only adult ADHD clinic in the country; however, due to logistical and travel constraints, most patients come from the urbanized Muscat capital region and its surrounding areas.

The primary outcome measure was improvement in ADHD symptoms following treatment with methylphenidate versus atomoxetine. This was assessed using the Clinical Global Impressions Scale-Improvement (CGI-I) scale, capable of detecting a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5) with a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%. Within the SD derived from previous studies,5 the calculated sample size was approximately 90 participants per group. To account for potential dropouts and exclusions, we planned to enroll at least 120 participants attending from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2023. This sample size was considered sufficient to detect significant clinical improvements attributable to the given ADHD medication.

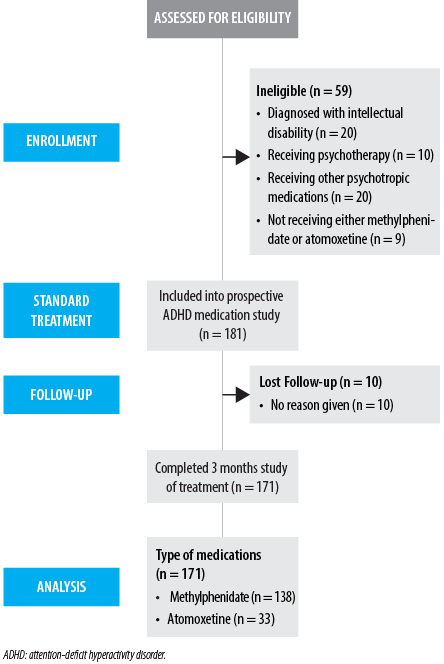

All participants in this study were referred from primary or secondary healthcare facilities in Oman. The study included Omani adults (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with ADHD and who had undergone treatment for at least three months. Non-Omani were excluded. To ensure that any observed improvements could be specifically attributed to the ADHD medication used during the study, patients with psychometric evidence of comorbid intellectual disabilities were excluded if they scored below the 25th percentile on Raven’s Progressive Matrices. This non-verbal test evaluates current reasoning ability and fluid intelligence.9 We also excluded patients on other psychotropic medications, those who were not in compliance with their ADHD medications, and those undergoing other psychotherapeutic or alternative and complementary treatments. The flow chart in Figure 1 depicts the process of selection and categorization of participants.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for study participants.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for study participants.

Demographic and clinical data collected included sex, marital status, and level of education. Body mass index was recorded in line with World Health Organization guidance, which identifies overweight and obesity as health risks.10 Participants were also asked to report whether any member of the family had a history suggestive of ADHD or specific developmental disorders. Other background information included any history of suicidal attempts, previous forensic involvement, or prior psychiatric hospital admissions.

Psychiatric comorbidities were assessed via the Arabic version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.11 Specific subscales were used to determine substance dependence (alcohol and non-alcohol), bipolar affective disorder, major depressive episodes, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and psychotic disorders. Remaining psychiatric diagnoses were classified collectively as ‘any psychiatric comorbidity.’ Personality disorders were assessed via protracted interviews and collateral history, which enabled evaluation of maladaptive personality traits, distorted perceptions of reality, abnormal behaviors, and distress across various aspects of life (e.g., work, relationships, and social functioning) where these appeared to deviate from cultural expectations in at least two areas.

The ADHD diagnosis was confirmed through a two-step process. First, a comprehensive retrospective assessment of childhood symptoms was conducted using the Wender Utah Rating Scale, a 25-item self-report checklist designed to evaluate childhood symptoms and behaviors consistent with ADHD that persist into adulthood.12 Wender Utah Rating Scale is a Likert scale with responses ranging from ‘not at all or very slightly’ (score 0) to ‘very much (score 4). An overall score of ≥ 46 indicates a history of childhood ADHD.13 Second, the evaluation of current adult ADHD was acquired through the Conners Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV.14 A senior child psychiatrist conducted is semi-structured interview.

The study adopted a naturalistic observation protocol. Our institution follows a flexible patient-centered approach. Methylphenidate, a central nervous system stimulant, is our typical first-line treatment for adult ADHD. However, atomoxetine is used as a first-line option in a minority of cases—usually for patients who do not respond to methylphenidate, have significant comorbid anxiety, or have a history of substance use disorders. Some patients prefer non-stimulants due to their extended duration of action or to avoid stimulant-related side effects. All medications are initiated at low dosages and titrated based on the individual patient’s response and tolerability.

Participants were encouraged to refrain from all other treatments for ADHD during the observation period. Before starting pharmacotherapy, all participants were tested for substance misuse. This was repeated at subsequent four-weekly follow-ups to ensure that illicit drugs did not assist any improvement.

In the methylphenidate protocol, the treatment was initiated with either short or extended-release methylphenidate at 20 mg per day, gradually increasing to a maximum of 60 mg in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.15 These recommend starting at 5–10 mg daily and titrating as needed in 5–10 mg weekly increments, up to 60 mg per day. At each four-week follow-up visit, clinicians assessed medication adherence, core ADHD symptoms, blood pressure, heart rate, weight, other mental health symptoms, functional outcomes, and adverse reactions.

In the atomoxetine protocol, the treatment began with an oral dose of 40 mg per day, which could be increased to a maintenance dose of 80 mg per day after three days.

CGI-I scale was used to document the treatment outcome.16 This 7-point clinician-scored index compares a patient’s current symptoms and overall functioning to baseline with ratings as follows: 1 = very much improved; 2 = much improved; 3 = minimally improved; 4 = no change; 5 = minimally worse; 6 = much worse; 7 = very much worse. For the purposes of this study, a positive treatment response was defined as a patient experiencing ‘very good’ to ‘good improvement’ in CGI, or a composite score of CGI-I > 2.

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp. Release 2022. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Continuous information was presented as mean ± SD, and categorical data as frequency and percentages. Categorical associations were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous data between groups were compared using the independent t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman (Ref: MREC 2260). All participants provided their written informed consent. The study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki17 and the American Psychological Association.

Results

The participants comprised 171 Omani adults with a mean age of 25.8 ± 6.8 years, and a male majority (60.8%). Inattention-type ADHD was the most common clinical presentation (66.1%), followed by combined ADHD with hyperactivity and inattention (24.0%), and hyperactivity (9.9%). Substance use was found in 29.2% of the patients, and 24.0% had a family history of ADHD. Depressive disorders and anxiety disorders were found in 17.5% and 26.3% of patients, respectively, and 72.5% had at least one psychiatric comorbidity. Most patients (80.7%) were treated with methylphenidate, while 19.3% received atomoxetine [Table 1].

Table 1: Baseline demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of Omani adults with ADHD compared with treatment response based on CGI-I (N = 171).

|

Age

|

25.8 ± 6.8

|

25.1 ± 5.4

|

25.9 ± 7.1

|

0.586

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female

|

67 (39.2)

|

16 (57.1)

|

51 (35.7)

|

0.055

|

|

Male

|

104 (60.8)

|

12 (42.9)

|

92 (64.3)

|

|

|

BMI (n = 153)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Underweight

|

18 (11.8)

|

3 (12.5)

|

15 (11.6)

|

0.429

|

|

Normal

|

71 (46.4)

|

13 (54.2)

|

58 (45.0)

|

|

|

Pre-obesity

|

32 (20.9)

|

6 (25.0)

|

26 (20.2)

|

|

|

Obesity

|

32 (20.9)

|

2 (8.3)

|

30 (23.3)

|

|

|

Marital status

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single

|

141 (82.5)

|

22 (78.6)

|

119 (83.2)

|

0.589

|

|

Married

|

30 (17.5)

|

6 (21.4)

|

24 (16.8)

|

|

|

Education (n = 165)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than high school

|

16 (9.7)

|

3 (11.5)

|

13 (9.4)

|

0.806

|

|

High school

|

66 (40.0)

|

9 (34.6)

|

57 (41.0)

|

|

|

Bachelor’s degree

|

40 (24.2)

|

8 (30.8)

|

32 (23.0)

|

|

|

Master’s and professionals

|

43 (26.1)

|

6 (23.1)

|

37 (26.6)

|

|

|

Clinical presentation of ADHD

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hyperactivity

|

17 (9.9)

|

1 (3.6)

|

16 (11.2)

|

0.262

|

|

Inattention

|

113 (66.1)

|

22 (78.6)

|

91 (63.6)

|

|

|

Mixed (hyperactivity and inattention)

|

41 (24.0)

|

5 (17.9)

|

36 (25.2)

|

|

|

Substance use disorder

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

50 (29.2)

|

8 (28.6)

|

42 (29.4)

|

1.000

|

|

Absent

|

121 (70.8)

|

20 (71.4)

|

101 (70.6)

|

|

|

Family history of ADHD

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

41 (24.0)

|

11 (39.3)

|

30 (21.0)

|

0.052

|

|

Absent

|

130 (76.0)

|

17 (60.7)

|

113 (79.0)

|

|

|

Psychotic disorders

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

2 (1.2)

|

1 (3.6)

|

1 (0.7)

|

0.301

|

|

Absent

|

169 (98.8)

|

27 (96.4)

|

142 (99.3)

|

|

|

Bipolar affective disorder

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

24 (14.0)

|

3 (10.7)

|

21 (14.7)

|

0.769

|

|

Absent

|

147 (86.0)

|

25 (89.3)

|

122 (85.3)

|

|

|

Personality disorders

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

27 (15.8)

|

3 (10.7)

|

24 (16.8)

|

0.575

|

|

Absent

|

144 (84.2)

|

25 (89.3)

|

119 (83.2)

|

|

|

Depressive disorders

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

30 (17.5)

|

8 (28.6)

|

22 (15.4)

|

0.106

|

|

Absent

|

141 (82.5)

|

20 (71.4)

|

121 (84.6)

|

|

|

Anxiety disorders

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

45 (26.3)

|

11 (39.3)

|

34 (23.8)

|

0.103

|

|

Absent

|

126 (73.7)

|

17 (60.7)

|

109 (76.2)

|

|

|

OCD

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

5 (2.9)

|

-

|

5 (3.5)

|

0.593

|

|

Absent

|

166 (97.1)

|

28 (100.0)

|

138 (96.5)

|

|

|

Any psychiatric comorbidity

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

124 (72.5)

|

22 (78.6)

|

102 (71.3)

|

0.496

|

|

Absent

|

47 (27.5)

|

6 (21.4)

|

41 (28.7)

|

|

|

History of scholastic developmental disorders

|

|

Present

|

13 (7.6)

|

2 (7.1)

|

11 (7.7)

|

1.000

|

|

Absent

|

158 (92.4)

|

26 (92.9)

|

132 (92.3)

|

|

|

Previous suicidal attempt

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

10 (5.8)

|

3 (10.7)

|

7 (4.9)

|

0.212

|

|

Absent

|

161 (94.2)

|

25 (89.3)

|

136 (95.1)

|

|

|

Previous forensic history

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

1 (0.6)

|

-

|

1 (0.7)

|

1.000

|

|

Absent

|

170 (99.4)

|

28 (100.0)

|

142 (99.3)

|

|

|

Previous hospital admission

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

12 (7.0)

|

3 (10.7)

|

9 (6.3)

|

0.418

|

|

Absent

|

159 (93.0)

|

25 (89.3)

|

134 (93.7)

|

|

|

Medication for ADHD

|

|

|

|

|

|

Atomoxetine (n = 33)

|

33 (19.3)

|

7/33 (21.2)

|

26/33 (78.8)

|

0.434

|

ADHD: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CGI-I: clinical global impressions-improvement scale; BMI: body mass index; OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder.

Table 1 also presents the treatment results on the CGI-I scale, with a significant improvement shown by 83.6% of participants. Individually, 78.8% of atomoxetine-treated patients and 84.8% of methylphenidate-treated patients improved.

Table 2 presents the multivariate logistic regression model. The overall model was statistically significant (χ² = 18.73, df = 4, p < 0.001), indicating that the included predictors reliably differentiated between treatment responders and non-responders, with Cox-Snell R2 explaining 7.0% of the variations. After adjustment, two covariates predicted a statistically significant CGI-I response to treatment: being male (p = 0.044) and having no family history of ADHD (p = 0.020). The advantages associated with the absence of depressive or anxiety disorders did not reach statistical significance [Table 2].

Table 2: Predictors of positive treatment response (CGI-I) in Omani adults with ADHD: multivariate logistic regression results (N = 171).

|

Sex, male

|

0.883

|

0.439

|

0.044*

|

2.42

|

1.02 – 5.71

|

|

Absent family history of ADHD

|

1.076

|

0.464

|

0.020*

|

2.93

|

1.18 – 7.28

|

|

Absence of depressive disorders

|

0.693

|

0.525

|

0.186

|

2.00

|

0.72 – 5.59

|

*Significant; CGI-I: clinical global impressions-improvement scale; ADHD: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; β: regression coefficient; SE: standard error; OR: odds ratio.

Discussion

This naturalistic study provides insights into the routine pharmacological treatment and predictors of response among 171 Omani adults with ADHD. To our knowledge, this is the first such study in the Arabian Gulf region.

In this cohort, 60.8% were men and 39.2% were women, consistent with the global trend of higher male prevalence in ADHD in both adults and children.18 Similarly, in community and healthcare settings, boys and men with ADHD typically display more overt hyperactivity and impulsivity—traits that are more noticed and reported by teachers, parents, and healthcare providers. Girls and women are more likely to have the inattention subtype, which is often overlooked or misdiagnosed as anxiety or depression.19 In traditional societies such as Oman, cultural and social norms may further accentuate the apparent male predominance, due to their greater public visibility.

Inattentive type ADHD was the most common (66.1%), followed by combined (24.0%) and hyperactive (9.9%) types. Type. Previous research has also found inattentive ADHD-type in most adults.20 Evidence suggests that these three ADHD subtypes differ in their associated cognitive profiles. For example, LeRoy et al.21 reported that variation in memory status was the only domain that differentiated ADHD-Inattentive and ADHD-combined subtypes from controls.

Substance use disorder was present in 29.2% of participants. In a large study of 18 167 adult Swedish twins aged 20–45 years, ADHD symptoms were associated with an increased probability of all substance use disorder outcomes, including nicotine, multiple drug use, and alcohol dependence.22 In our study, all illegal drugs were screened to control for their potential confounding effect, as substance has been hypothesized as a form of self-medication in individuals with ADHD.23 Some researchers have proposed that the temperament of people with ADHD symptoms leans towards behavioral activation system—linked to impulsivity—rather than the anxiety-driven behavioral inhibition system. In substance abusers with ADHD symptoms, behavioral inhibition system-related traits were positively correlated with a variation in ADHD symptoms. Zayman et al,24 suggest that substance use in this context may serve to increase pleasure and reduce symptoms of ADHD, rather than being purely impulsive behavior.

Our participants exhibited a high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders (72.5%). Depressive disorders and anxiety disorders were found in 17.5% and 26.3% of the participants, respectively. More than half of a Japanese cohort of adult ADHD patients had a prevalence of at least one comorbid psychiatric condition.25 A critical review of literature from 1978 to December 2005 found that the comorbidity rate was higher in adult patients with ADHD compared to children, with up to 80% of adults reporting at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder.26 This could be because of complex inter-related factors, one of which could be untreated childhood ADHD, generating maladaptive coping behavior, which may increase the chances of comorbidities in adulthood. Another reason could be differences in diagnostic methods and criteria.27 This suggests that identification and treatment for ADHD should begin in childhood, which could reduce the chances of the development of serious comorbidities.

Regarding treatment, 80.7% of our participants received methylphenidate, and only 19.3% were prescribed atomoxetine. Improvement rates were high, at 84.8% for methylphenidate and 78.8% for atomoxetine (p = 0.434). Our improvement rate with methylphenidate exceeded the 76% response in a randomized controlled trial in the USA.28 Atomoxetine treatment in the current study began with a daily dose of 40 mg, which was titrated according to patient response. A shift of medication between methylphenidate and atomoxetine was considered only after six weeks of non-response or intolerance to either drug. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline,15 the suggested starting dose for atomoxetine is 0.5mg/kg/day for people under 70 kg, to be gradually increased to a maximum of 120 mg. Above 70 kg, the recommended initial dose is 40 mg daily. We did not find a significant association between the type of medication and the results of treatment, in line with previous studies.29

In this study, the absence of a family history of ADHD was a significant predictor of response to medications. This is corroborated by a previous study, which correlated a family history of ADHD with non-adherence.30 Furthermore, non-adherence was associated with poorer response and lower improvement in the CGI-ADHD scale.30 This indicates a possible genetic influence on treatment outcomes in the Omani adult ADHD population, and adds valuable data useful for the ongoing research on the interplay between genetic and environmental factors in ADHD.31

Our study showed that men had a slightly higher improvement compared to women, which is consistent with previous research that revealed that women feel more impaired than men with similar levels of symptoms.32 Furthermore, men have a higher density of dopamine receptors,33 which is the main target of ADHD medications. These biological differences highlight the importance of considering sex-specific factors in ADHD management, for which more research is needed.

Furthermore, our participants without anxiety showed greater improvement, which aligns with previous research suggesting that comorbid anxiety and bipolar disorders are associated with a decreased response to treatment,and a worse clinical presentation.34,35

The modest explanatory power of our regression model (≈ 7.0%) highlights the multifactorial nature of treatment outcomes in adult ADHD. Although identified factors provide valuable information, additional unexplored variables can contribute to the remaining variance, including genetic markers, psychosocial factors, and medication adherence. Future research could investigate these aspects to refine predictive models and improve our understanding of the factors that influence response to treatment.

This prospective study had limitations. First of all, it was constrained by its non-interventional design, which precluded the assessment of causal relationships. Ideally, a randomized controlled study would have been more robust, and this would require attention in the future. However, by including all Omani adult patients from the country’s only ADHD clinic, this study provides a comprehensive view of routine clinical practice, which could reflect the generalizability of our research results. These findings provide practical guidance to clinicians and increase existing knowledge on the treatment outcomes of ADHD medication regimens.

Conclusion

This study found an overall 83.6% improvement rate in adult ADHD in Oman as measured by the CGI-I scale. Methylphenidate showed a higher but non-significant treatment response compared to atomoxetine. There was a high prevalence of comorbid conditions, highlighting the importance of adopting a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses both ADHD symptoms and any concurrent mental health problems. By recognizing and treating comorbidities along with ADHD, clinicians can optimize outcomes and improve overall patient well-being. Furthermore, the absence of a family history of ADHD was associated with improved response to both methylphenidate and atomoxetine, suggesting its potential as a prognostic indicator in treatment decisions.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Di Lorenzo R, Balducci J, Poppi C, Arcolin E, Cutino A, Ferri P, et al. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: a systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2021 Dec;33(6):283-298.

- 2. Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2021 Feb;11:04009.

- 3. Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Adamowski T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al; WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV adult ADHD in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2017 Mar;9(1):47-65.

- 4. Al-Wardat M, Etoom M, Almhdawi KA, Hawamdeh Z, Khader Y. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents and adults in the Middle East and North Africa region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024;14(1):e078849.

- 5. Bedawi RM, Al-farsi Y, Mirza H, Al-huseini S, Al-mahrouqi T, Al-kiyumi O, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of adults with ADHD attending a tertiary care hospital for five years. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024 Apr;21(5):566.

- 6. Mészáros A, Czobor P, Bálint S, Komlósi S, Simon V, Bitter I. Pharmacotherapy of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009 Sep;12(8):1137-1147.

- 7. Radonjić NV, Bellato A, Khoury NM, Cortese S, Faraone SV. Nonstimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 2023 May;37(5):381-397.

- 8. Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, Mohr-Jensen C, Hayes AJ, Carucci S, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2018 Sep;5(9):727-738.

- 9. Abdel-khalek AM, Lynn R. Norms for intelligence assessed by the standard progressive matrices in Oman. Mankind Quarterly 2008 Dec;49(2):183.

- 10. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2024 [cited 2025 May 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- 11. Chamali R, Ghuloum S, Sheehan DV, Mahfoud Z, Yehya A, Opler MG, et al. Cross-validation of the arabic mini international neuropsychiatric interview, module k, for diagnosis of schizophrenia and the arabic positive and negative syndrome scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2020;42(1):139-149.

- 12. Gift TE, Reimherr ML, Marchant BK, Steans TA, Reimherr FW. Wender Utah rating scale: psychometrics, clinical utility and implications regarding the elements of ADHD. J Psychiatr Res 2021 Mar;135:181-188.

- 13. Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah rating scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993 Jun;150(6):885-890.

- 14. Epstein J, Johnson DE, Conners CK. Conners’ adult ADHD diagnostic interview for DSM-IVTM. Multi-Health Syst Inc. 1999 [cited 2025 August 4]. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft04960-000.

- 15. Guidelines N. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. Guidance. NICE. 2018 [cited 2018 March 4]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87/chapter/recommendations#medication-choice-adults.

- 16. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4(7):28-37.

- 17. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 1975.

- 18. Faheem M, Akram W, Akram H, Khan MA, Siddiqui FA, Majeed I. Gender-based differences in prevalence and effects of ADHD in adults: a systematic review. Asian J Psychiatr 2022 Sep;75:103205.

- 19. Attoe DE, Climie EA. Miss. diagnosis: a systematic review of ADHD in adult women. J Atten Disord 2023;27(7):645-657.

- 20. Ayano G, Tsegay L, Gizachew Y, Necho M, Yohannes K, Abraha M, et al. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: umbrella review of evidence generated across the globe. Psychiatry Res 2023 Oct;328:115449.

- 21. LeRoy A, Jacova C, Young C. Neuropsychological performance patterns of adult ADHD subtypes. J Atten Disord 2019 Aug;23(10):1136-1147.

- 22. Capusan AJ, Bendtsen P, Marteinsdottir I, Larsson H. Comorbidity of adult ADHD and its subtypes with substance use disorder in a large population-based epidemiological study. J Atten Disord 2019 Oct;23(12):1416-1426.

- 23. Silva N Jr, Szobot CM, Shih MC, Hoexter MQ, Anselmi CE, Pechansky F, et al. Searching for a neurobiological basis for self-medication theory in ADHD comorbid with substance use disorders: an in vivo study of dopamine transporters using (99m)Tc-TRODAT-1 SPECT. Clin Nucl Med 2014 Feb;39(2):e129-e134.

- 24. Zayman EP, Ünal S, Cumurcu HB, Özcan ÖÖ, Bilici R, Zayman E. Investigation of the relationship between adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and reinforcement sensitivity in substance use disorders? Klin Psikiyatri Derg 2024;27(1):74-82.

- 25. Ohnishi T, Kobayashi H, Yajima T, Koyama T, Noguchi K. Psychiatric comorbidities in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: prevalence and patterns in the routine clinical setting. Innov Clin Neurosci 2019;16(9-10):11-16.

- 26. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2007 Jun;164(6):942-948.

- 27. Choi WS, Woo YS, Wang SM, Lim HK, Bahk WM. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in adult ADHD compared with non-ADHD populations: a systematic literature review. PLoS One 2022 Nov;17(11):e0277175.

- 28. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Doyle R, Surman C, Prince J, et al. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005 Mar;57(5):456-463.

- 29. Benkert D, Krause K-H, Wasem J, Aidelsburger P. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical therapy of ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in adults – health technology assessment. GMS Health Technol Assess 2010; 6:Doc13.

- 30. Hong J, Novick D, Treuer T, Montgomery W, Haynes VS, Wu S, et al. Predictors and consequences of adherence to the treatment of pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Central Europe and East Asia. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013 Sep;7:987-995.

- 31. Zheng Y, Pingault JB, Unger JB, Rijsdijk F. Genetic and environmental influences on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal twin study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020;29(2):205-216.

- 32. Williamson D, Johnston C. Gender differences in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a narrative review. Clin Psychol Rev 2015 Aug;40:15-27.

- 33. Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptors and their relevance to ADHD. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2000 Jan;24(1):137-141.

- 34. Skirrow C, Asherson P. Emotional lability, comorbidity and impairment in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Affect Disord 2013 May;147(1-3):80-86.

- 35. Quenneville AF, Kalogeropoulou E, Nicastro R, Weibel S, Chanut F, Perroud N. Anxiety disorders in adult ADHD: a frequent comorbidity and a risk factor for externalizing problems. Psychiatry Res 2022 Apr;310:114423.