Herpes zoster (HZ), commonly known as shingles, is a health challenge, particularly among the elderly.1 Its prevalence varies across epidemiological studies, typically ranging from 3 to 5 cases per 1000 person-years, with a significance of 8–12 per 1000 among those older than 50.2,3 The condition results from the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which remains dormant in sensory ganglia following primary varicella infection (chickenpox). Clinically, HZ manifests as a painful vesicular rash distributed along specific dermatomes on one side of the body.4

Beyond the acute phase, HZ can lead to long-term complications such as post-herpetic neuralgia affects approximately 30% of patients and is characterized by chronic neuropathic pain that can persist for six months or longer, profoundly impacting quality of life.1,5 The economic burden of HZ is substantial, with annual treatment costs reaching USD 1.1 billion in the US and €1.7 billion in the European Union.6 These figures do not account for indirect costs, such as productivity losses, estimated to exceed USD 3

billion globally.7,8

The introduction of the recombinant zoster vaccine has provided a highly effective preventive measure, with > 90% efficacy across all age groups, including immunocompromised individuals.9,10 In Saudi Arabia, the HZ vaccine is provided free of charge under the national healthcare system. However, it has not yet been integrated into the life course vaccination program, and vaccine coverage rates remain low, reflecting limited accessibility and awareness of its availability. Additionally, no formal national schedule for HZ vaccination exists.

In Saudi Arabia, the epidemiology of HZ presents unique challenges. Studies indicate a relatively high incidence of 4.7 cases per 1000 person-years, likely due to the relatively high life expectancy in the Kingdom, in addition to a growing population of immunocompromised individuals.11 A survey by Al-Muammar et al,12 among Saudi Arabian adults revealed that while 57.2% of participants were aware of the shingles vaccine, only 7.7% had received it. Furthermore, Alhazmi et al,13 found that 58% of older adults in the Jazan region had limited knowledge of HZ and its vaccination, with significant variations by age, professional level, and employment status.

The Jazan region, with its population of 1.5 million and distinct socioeconomic and healthcare dynamics, warrants targeted research on HZ vaccination.14,15 This study aims to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary healthcare physicians in Jazan regarding HZ vaccination and identify factors influencing these dimensions. Our results will inform policymakers and physicians towards more targeted interventions to improve HZ vaccination coverage.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted in 2023 in the Jazan region in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Jazan has a population of approximately 1.5 million and is served by 168 primary healthcare centers (PHCCs) distributed across 14 administrative governorates. We targeted general practitioners (both Saudi nationals and expatriates).

The required sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula with finite population correction, based on a 95% CI, 5% margin of error, and an assumed proportion of 0.5. This yielded a minimum sample size of 240, which we increased by 20% to account for potential non-responses, resulting in a final target of 288.

A stratified random sampling method was employed to ensure proportional representation from all 14 governorates in Jazan. A comprehensive list of primary healthcare physicians was obtained from the Jazan Health Cluster. Simple random sampling was then applied to select participants from each governorate.

A 15-item questionnaire in English was developed following a literature review and expert consultation, based on a validated tool by Elkin ZP et al.16 The questionnaire comprised three main sections: demographic variables, knowledge scores on HZ and its vaccination, and beliefs and attitudes toward vaccination practices. The knowledge assessment part consisted of 15 questions, with each correct response scoring one point. The section on attitudes and beliefs utilized a Likert scale to evaluate factors such as vaccination practices, barriers, priorities, and implementation challenges. The validity, reliability, and internal consistency of the questionnaire were examined and found satisfactory. The Healthcare professionals’ self-reported practices regarding HZ vaccination were evaluated using a six-item questionnaire.

Data collection was conducted by distributing questionnaires via WhatsApp, a social media platform widely used in Saudi Arabia. Invitations were sent to 288 potential participants, of whom 281 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 97.6%.

We received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Jazan University (approval no. REC-45/09/1032). The study adhered to the revised Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each participant in advance. The data were stored on a password-protected server accessible only to the research team and reported in aggregate to protect participant identities.

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means standard deviations ± SD, ranges, and medians with IQR. Demographic characteristics associated with knowledge level were determined using the chi-squared test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the factors associated with knowledge, and the results were presented as adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI. Statistical findings were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

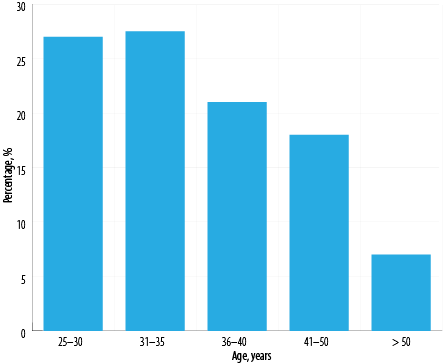

The study included 281 primary healthcare professionals, 164 (58.4%) of whom were male. Age group distribution was generally balanced, except for those aged > 50 years, who comprised 6.8% of the sample [Table 1; Figure 1]. Professional experience varied: 36.3% had < 5 years, 30.2% had 5–10 years, and 33.5% had > 10 years, providing a fair representation across career stages.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of primary care physicians (N = 281).

|

Age, years

|

|

|

|

25–30

|

75

|

26.7

|

|

31–35

|

76

|

27.0

|

|

36–40

|

59

|

21.0

|

|

41–50

|

52

|

18.5

|

|

> 50

|

19

|

6.8

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

|

Male

|

164

|

58.4

|

|

Female

|

117

|

41.6

|

|

Professional level

|

|

|

|

General practitioner

|

120

|

42.7

|

|

Family medicine junior resident

|

45

|

16.0

|

|

Family medicine senior resident

|

16

|

5.7

|

|

Family medicine specialist

|

62

|

22.1

|

|

Family medicine consultant

|

38

|

13.5

|

|

Nationality

|

|

|

|

Saudi

|

171

|

60.9

|

|

Non-Saudi

|

110

|

39.1

|

|

Experience, years

|

|

|

|

< 5

|

102

|

36.3

|

|

5–10

|

85

|

30.2

|

Figure 1: Age-group distribution of primary care physicians (N = 281).

Figure 1: Age-group distribution of primary care physicians (N = 281).

Regarding professional levels, general practitioners constituted the largest group (n = 120; 42.7%) followed by family medicine specialists and consultants (n = 100; 35.6%) and residents (n = 61; 21.7%). The majority (n = 171; 60.9%) were Saudi citizens [Table 1].

We assessed the participants’ knowledge of HZ vaccination using a 15-item questionnaire. Each accurate response received one point, yielding a potential score range of 0–15. The median score was used as the threshold to classify the participants’ knowledge as either adequate or inadequate. The questions and responses are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Healthcare professionals’ attitudes and perceptions towards HZ vaccination (N = 281).

|

1

|

Storage requirements make the HZ vaccine difficult to use.

|

109 (38.8)

|

82 (29.2)

|

3 (1.1)

|

73 (26.0)

|

14 (5.0)

|

|

2

|

Ordering/administering is too complicated.

|

132 (47.0)

|

79 (28.1)

|

-

|

59 (21.0)

|

11 (3.9)

|

|

3

|

Physicians unaware of recommendations.

|

78 (27.8)

|

78 (27.8)

|

-

|

101 (35.9)

|

24 (8.5)

|

|

4

|

Too busy to recommend HZ vaccine

|

75 (26.7)

|

73 (26.0)

|

-

|

102 (36.3)

|

31 (11.0)

|

|

5

|

All non-immunocompromised > 50 should be vaccinated.

|

45 (16.0)

|

54 (19.2)

|

-

|

64 (22.8)

|

118 (42.0)

|

|

6

|

Healthy patients not at risk for shingles.

|

128 (45.6)

|

93 (33.1)

|

-

|

49 (17.4)

|

11 (3.9)

|

|

7

|

Patients are vaccinated upon doctor recommendation.

|

43 (15.3)

|

77 (27.4)

|

-

|

93 (33.1)

|

68 (24.2)

|

|

8

|

Treatment is effective, prevention not a priority.

|

144 (51.2)

|

61 (21.7)

|

-

|

57 (20.3)

|

19 (6.8)

|

|

9

|

Other health issues take precedence.

|

67 (23.8)

|

111 (39.5)

|

-

|

82 (29.2)

|

21 (7.5)

|

|

10

|

Concern over co-morbidities in elderly.

|

90 (32.0)

|

85 (30.2)

|

-

|

81 (28.8)

|

25 (8.9)

|

|

11

|

HZ vaccination is a clinical priority.

|

42 (14.9)

|

54 (19.2)

|

-

|

86 (30.6)

|

99 (35.2)

|

|

12

|

Pneumococcal/flu vaccines are priorities.

|

40 (14.2)

|

60 (21.4)

|

-

|

76 (27.0)

|

105 (37.4)

|

|

13

|

CDC/ACIP guides my practice.

|

37 (13.2)

|

58 (20.6)

|

-

|

77 (27.4)

|

109 (38.8)

|

|

14

|

HZ vaccine is safe.

|

28 (10.0)

|

52 (18.5)

|

-

|

71 (25.3)

|

130 (46.3)

|

HZ: Herpes zoster; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ACIP: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

Concerning the practical aspects of HZ vaccine administration, most participants did not perceive significant logistic obstacles, with 191 (68.0%) not viewing vaccine storage constraints as a challenge and 211 (75.1%) disagreeing that processes for ordering and administering were overly complex [Table 2].

On the other hand, temporal limitations and conflicting priorities were perceived as critical challenges, with nearly half of the responders (n = 133; 47.3%) concurring that their clinical responsibilities prevented them from recommending HZ vaccination to patients, though 103 (36.7%) stated that their patients had expressed concerns about shingles.

Awareness and perception of vaccination recommendations also influenced outcomes. Almost half of the participants (n = 125; 44.5%) indicated that HZ immunization rates were low because physicians had insufficient understanding of guidelines. Meanwhile, the majority (n = 186; 66.2%) concurred that recommendations from entities such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) had a significant influence on their immunization behavior.

Most participants agreed that all non-immunocompromised individuals aged ≥ 50 years should receive the vaccine (n = 182; 64.8%), that HZ immunization was a significant clinical priority for patients (n = 185; 65.8%), and that it was safe (n = 201; 71.5%). The majority also disagreed that shingles prevention has low priority (n = 205; 73.0%) or that healthy individuals are not at risk of complications from shingles (n = 221; 78.6%). The majority of endorsements demonstrate good understanding of the risks faced by unvaccinated older individual. Opinions were more divided on whether physicians should recommend patients to vaccinate against shingles; here, a lower majority (n = 161; 57.3%) was in agreement.

Overall, our survey revealed that only 176 (62.6%) of participating physicians had sufficient knowledge regarding HZ vaccination [Table 3].

Table 3: Knowledge of healthcare professionals regarding herpes zoster vaccination (N = 281).

|

Insufficient

|

105 (37.4)

|

|

Sufficient

|

176 (62.6)

|

|

Score summary

|

|

Mean ± SD, (range)

|

8.0 ± 2.0 (1–15)

|

Table 4 describes primary physicians’ practices regarding the vaccinatination of their patients against shingles. Most respondents (n = 206; 73.3%) disagreed that they mostly administered the HZ vaccine only when patients requested it (42.3% strongly, 31.0% somewhat). Most participants (n = 177; 63.0%) did not consider that patients experience difficulty in accessing the HZ vaccine. However, the majority (n = 158, 56.2%) agreed that their older patients had a lack of interest in HZ vaccination [Table 4].

Table 4: Primary healthcare professionals’ self-reported practices regarding HZ vaccination (N = 281).

|

1

|

I mostly only give the HZ vaccine when patients request it.

|

119 (42.3)

|

87 (31.0)

|

64 (22.8)

|

11 (3.9)

|

|

2

|

My patients have trouble getting access to HZ vaccine.

|

75 (26.7)

|

102 (36.3)

|

88 (31.3)

|

16 (5.7)

|

|

3

|

My older patients are not interested in HZ vaccine.

|

40 (14.2)

|

83 (29.5)

|

133 (47.3)

|

25 (8.9)

|

|

4

|

I closely follow CDC (ACIP) guidelines in making vaccination decisions for my patients.

|

29 (10.3)

|

53 (18.9)

|

102 (36.3)

|

97 (34.5)

|

|

5

|

I know how to order the HZ vaccination within my practice environment.

|

27 (9.6)

|

60 (21.4)

|

91 (32.4)

|

103 (36.7)

|

HZ: Herpes zoster; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ACIP: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The majority of physicians reported being knowledgeable about vaccine ordering procedures (n = 194; 69.0%). Most physicians (n = 199; 70.8%) also acknowledged following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ACIP guidelines to make vaccination decisions for their patients.

Table 5 shows vaccine knowledge by demographic group. Knowledge was correlated borderline-positively with age (p = 0.050), peaking in the 31–35 age group. Notably, physicians over 50, though very few, had a disproportionately high rate of sufficient knowledge [Table 5].

Table 5: The association of demographic characteristics of healthcare professionals with their knowledge of herpes zoster vaccination (N = 281).

|

Age, years

|

|

|

|

|

0.050

|

|

25–30

|

35

|

33.3

|

40

|

22.7

|

|

|

31–35

|

25

|

23.8

|

51

|

29.0

|

|

|

36–40

|

22

|

21.0

|

37

|

21.0

|

|

|

41–50

|

21

|

20.0

|

31

|

17.6

|

|

|

> 50

|

2

|

1.9

|

17

|

9.7

|

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

|

|

0.038*

|

|

Male

|

53

|

50.5

|

111

|

63.1

|

|

|

Female

|

52

|

49.5

|

65

|

36.9

|

|

|

Professional level

|

|

|

|

|

0.027*

|

|

General practitioner

|

51

|

48.6

|

69

|

39.2

|

|

|

Family medicine junior resident

|

22

|

21.0

|

23

|

13.1

|

|

|

Family medicine senior resident

|

6

|

5.7

|

10

|

5.7

|

|

|

Family medicine specialist

|

19

|

18.1

|

43

|

24.4

|

|

|

Family medicine consultant

|

7

|

6.7

|

31

|

17.6

|

|

|

Nationality

|

|

|

|

|

0.325

|

|

Saudi

|

60

|

57.1

|

111

|

63.1

|

|

|

Non-Saudi

|

45

|

42.9

|

65

|

36.9

|

|

|

Experience, years

|

|

|

|

|

0.020*

|

|

< 5

|

49

|

46.7

|

53

|

30.1

|

|

|

5–10

|

27

|

25.7

|

58

|

33.0

|

|

*Significant.

Table 5 further reveals that male physicians are more likely to possess adequate knowledge of HZ vaccination (n = 111; 63.1%) compared to female participants (n = 65; 36.9%). The professional level showed a strong correlation with knowledge (p = 0.027), although the majority in each level had adequate knowledge. Experience was also significantly correlated with knowledge level (p = 0.020). Individuals with more than 10 years of experience were more likely to possess adequate knowledge. The physician's nationality was not correlated with their knowledge level (p = 0.325).

Table 6 presents a multivariate logistic regression analysis, where years of experience emerged as the only significant factor; professionals with 5–10 years of experience showed significantly higher odds ratio of having sufficient knowledge (aOR = 2.700, 95% CI: 1.058–6.889; p = 0.038).

Table 6: Demographic predictors of knowledge of herpes zoster vaccination as revealed by multivariate logistic regression analysis (N = 281).

|

Age, years

|

|

|

25–30

|

Reference Category

|

|

31–35

|

-0.051

|

0.909

|

0.951

|

0.400

|

2.257

|

|

36–40

|

-0.266

|

0.668

|

0.767

|

0.227

|

2.586

|

|

41–50

|

-0.122

|

0.863

|

0.885

|

0.219

|

3.569

|

|

> 50

|

1.371

|

0.180

|

3.938

|

0.530

|

29.266

|

|

Gender, Female

|

-0.434

|

0.108

|

0.648

|

0.381

|

1.101

|

|

Education

|

|

|

General practitioner

|

Reference Category

|

|

Family medicine junior resident

|

-0.086

|

0.829

|

0.917

|

0.420

|

2.005

|

|

Family medicine senior resident

|

0.246

|

0.669

|

1.279

|

0.414

|

3.948

|

|

Family medicine specialist

|

0.368

|

0.336

|

1.445

|

0.683

|

3.056

|

|

Family medicine consultant

|

0.396

|

0.511

|

1.486

|

0.456

|

4.842

|

|

Nationality, non-Saudi

|

-0.779

|

0.117

|

0.459

|

0.173

|

1.214

|

|

Experience, years

|

|

|

<5

|

Reference Category

|

|

5–10

|

0.993

|

0.038*

|

2.700

|

1.058

|

6.889

|

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Discussion

This survey revealed that 62.6% of primary care physicians in Jazan province of Saudi Arabia were aware of the HZ vaccination’s importance in preventing shingles in older adults. Another study among physicians in Makkah found that a significant majority (80.4%) were aware of shingles, and 88.2% had heard about the vaccine.15 A survey conducted in 2013 found that Korean physicians were generally knowledgeable about the shingles vaccine but less enthusiastic, likely due to its novelty, having been approved only in 2009.17 But as recent studies, including ours, suggest, most physicians are well-informed and positive about the vaccine. However, the existence of a significant minority of physicians without adequate knowledge of HZ vaccination can potentially impact patient care and public health efforts. This calls for strategies such as incorporating HZ vaccination training into continuous professional development programs (CPD) for primary care physicians.

Our findings indicate that > 5 years of clinical experience is significantly correlated with adequate knowledge of HZ vaccination. Other studies also reveal a similar trend.18,19 This underscores the importance of targeted educational initiatives for less experienced physicians, including residents.

Sex disparities in knowledge were observed among our participants, with male physicians demonstrating higher knowledge levels compared to other studies (p = 0.038.).15,20 This contrasts with findings elsewhere, which found female physicians to be more knowledgeable,19 needing further investigation. The observed difference may also be influenced by regional sociocultural factors, disparities in professional development opportunities, or varying roles within healthcare settings. It is essential to address them through equitable access to training and awareness programs.

The current results indicate that many Saudi patients, especially the elderly, are resistant to physicians’ advice to vaccinate themselves against HZ. This highlights the need for more culturally suitable counseling tools and wider public education to improve patient engagement, in addition to streamlining the vaccination process in PHCCs.

This study identified major barriers to the implemention of vaccination. Although 71.5% of physicians believed the vaccine to be safe and 65.8% believed it to be clinically relevant, almost half (47.3%) mentioned time constraints as a barrier. This gap between knowledge and practice is an important challenge in other parts of the world as well, with many studies reporting that primary care physicians have inadequate time to discuss vaccination with their patients.21,22 In the US 45% of healthcare providers reported not having enough time to perform vaccination.23 In a traditional society such as Saudi Arabia, physicians can be expected to face even more challenges in counseling resistant patients, especially the elderly.23

Supply chain requirements and ordering procedures for the shingles vaccine at PHCCs were not perceived as significant barriers by 68.0% of our participants, indicating relatively robust logistics. In a survey of ten American primary healthcare providers catering to geriatric patients, 60% (6/10) reported vaccine shortage at their centers, and 50% (5/10) stated tha- they had referred patients to outside facilities.24 Four (40%) providers indicated reimbursement and storage related concerns.24 However, older patients in the US were less vaccine resistant according to 80% (8/10) of these geriatric care providers.24 In contrast, most primary care physicians (56.2%) in the present study endorsed vaccine resistance in their older patients, suggesting a potential cultural barrier. On the positive side, 57.3% of Saudi physicians said their patients were willing to be vaccinated if recommended by their physician. This suggests our physicians may have the ability to promote HZ vaccinations among resistant Saudi patients. Studies from other parts of the world also endorse physicians’ persuasive power in promoting vaccination.25,26

Most (70.8%) of our respondents confirmed that their vaccination strategies were informed by professional recommendations such as those of the ACIP. Other studies also support this trend.27,28

The positive influence of professional level on knowledge score (p = 0.027) in the current study is endorsed by other studies, which found improved vaccination knowledge and practice to be outcomes of specialized medical training.29,30 The fact that professional education and knowledge are closely tied points to the need for increase investment

in CPD.

The limitations of this study include its reliance on self-reported data, which may be subject to potential response and social desirability biases, leading to overestimation of knowledge and adherence to recommended practices. Additionally, the findings are specific to the Jazan region, and caution is warranted when generalizing to other areas of Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

This study shows that while most primary care physicians had adequate knowledge of HZ vaccination, gaps persist in practice, mainly due to barriers such as patient resistance and time constraints. Training programs are needed to equip doctors with the skills to effectively counsel traditional, especially older, patients. As clinical experience and professional level are linked to better knowledge, we recommend HZ vaccination training as part of continuous professional development programs for junior doctors and residents. Similar studies in other regions are needed to support broader improvements in HZ vaccination rates across Saudi Arabia.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Pan CX, Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. Global herpes zoster incidence, burden of disease, and vaccine availability: a narrative review. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother 2022 Mar;10:25151355221084535.

- 2. Koshy E, Mengting L, Kumar H, Jianbo W. Epidemiology, treatment and prevention of herpes zoster: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84(3):251-262.

- 3. van Oorschot D, Vroling H, Bunge E, Diaz-Decaro J, Curran D, Yawn B. A systematic literature review of herpes zoster incidence worldwide. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021 Jun;17(6):1714-1732.

- 4. Johnson RW, Alvarez-Pasquin M-J, Bijl M, Franco E, Gaillat J, Clara JG, et al. Herpes zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: a multidisciplinary perspective. Ther Adv Vaccines 2015 Jul;3(4):109-120.

- 5. Aggarwal A, Suresh V, Gupta B, Sonthalia S. Post-herpetic neuralgia: a systematic review of current interventional pain management strategies. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2020;13(4):265-274.

- 6. Williams WW, Lu PJ, O’Halloran A, Kim DK, Grohskopf LA, Pilishvili T, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance of vaccination coverage among adult populations - United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016 Feb;65(1):1-36.

- 7. Panatto D, Bragazzi NL, Rizzitelli E, Bonanni P, Boccalini S, Icardi G, et al. Evaluation of the economic burden of herpes zoster (HZ) infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015;11(1):245-262.

- 8. Blein C, Gavazzi G, Paccalin M, Baptiste C, Berrut G, Vainchtock A. Burden of herpes zoster: the direct and comorbidity costs of herpes zoster events in hospitalized patients over 50 years in France. BMC Infect Dis 2015 Aug;15:350.

- 9. Parikh R, Singer D, Chmielewski-Yee E, Dessart C. Effectiveness and safety of recombinant zoster vaccine: a review of real-world evidence. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023 Dec;19(3):2263979.

- 10. Syed YY. Recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix®): a review in herpes zoster. Drugs Aging 2018 Dec;35(12):1031-1040.

- 11. Alharbi S, Alsubaie M, Alzayyat R, Alattas B, AlAhmadi H, Alabdullatif H. Herpes zoster virus reactivation in a 16 year old female post COVID-19 vaccine. case report and review of the literature. Med Arch 2023 Apr;77(2):146-149.

- 12. AlMuammar S, Albogmi A, Alzahrani M, Alsharef F, Aljohani R, Aljilani T. Herpes zoster vaccine awareness and acceptance among adults in Saudi Arabia: a survey-based cross-sectional study. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 2023 Oct;9(1):17.

- 13. Alhazmi AH, Jaafari H, Hufaysi AH, Alhazmi AK, Harthi F, Hakami TK, et al. Knowledge of herpes zoster virus and its vaccines among older adults in Jazan province, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus 2024 Sep;16(9):e68726.

- 14. Gosadi IM. Epidemiology of communicable diseases in Jazan region: situational assessment, risk characterization, and evaluation of prevention and control programs outcomes. Saudi Med J 2023 Nov;44(11):1073-1084.

- 15. Turkistani SA, Althobaiti FJ, Alzahrani SH. The knowledge, attitude and practice among Makkah physicians towards herpes zoster vaccination, Saudi Arabia, 2023. Cureus 2023 Nov;15(11):e49393.

- 16. Elkin ZP, Cohen EJ, Goldberg JD, Li X, Castano E, Gillespie C, et al. Improving adherence to national recommendations for zoster vaccination through simple interventions. Eye Contact Lens 2014 Jul;40(4):225-231.

- 17. Yang TU, Cheong HJ, Choi WS, Song JY, Noh JY, Kim WJ. Physician attitudes toward the herpes zoster vaccination in South Korea. Infect Chemother 2014 Sep;46(3):194-198.

- 18. Alleft LA, Alhosaini LS, Almutlaq HM, Alshayea YM, Alshammari SH, Aldosari MA, et al. Public knowledge, attitude, and practice toward herpes zoster vaccination in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023 Nov;15(11):e49396.

- 19. Bohamad AH, Alojail HY, Alabdulmohsin LA, Alhawl MA, Aldossary MB, Altoraiki FM, et al. Knowledge about the herpes zoster (HZ) vaccine and its acceptance among the population in Al-Ahsa city in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023 Dec;15(12):e50329.

- 20. Alfandi N, Alhassan Z, Alfandi N, Alsobie S, Alkhalaf B, Ahmed F, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices of herpes zoster vaccination among the general population in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. J Health Sci 2024;4(1):11-22.

- 21. Chen J, Shantakumar S, Si J, Gowindah R, Parikh R, Chan F, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward herpes zoster (HZ) and HZ vaccination: concept elicitation findings from a multi-country study in the Asia Pacific. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2024 Dec;20(1):2317446.

- 22. Freedman S, Golberstein E, Huang TY, Satin DJ, Smith LB. Docs with their eyes on the clock? The effect of time pressures on primary care productivity. J Health Econ 2021 May;77:102442.

- 23. Williams WW, Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, Bridges CB, Kim DK, Pilishvili T, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015 Feb;64(4):95-102.

- 24. Montag Schafer K, Reidt S. Assessment of perceived barriers to herpes zoster vaccination among geriatric primary care providers. Pharmacy (Basel) 2016 Oct;4(4):30.

- 25. MacDonald NE, Butler R, Dubé E. Addressing barriers to vaccine acceptance: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018 Jan;14(1):218-224.

- 26. Alfageeh EI, Alshareef N, Angawi K, Alhazmi F, Chirwa GC. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among the Saudi population. Vaccines (Basel) 2021 Mar;9(3):1-13.

- 27. Hunter P, Fryhofer SA, Szilagyi PG. Vaccination of adults in general medical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2020 Jan;95(1):169-183.

- 28. Day P, Strenth C, Kale N, Schneider FD, Arnold EM. Perspectives of primary care physicians on acceptance and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination. Fam Med Community Health 2021 Nov;9(4):e001228.

- 29. Dybsand LL, Hall KJ, Carson PJ. Immunization attitudes, opinions, and knowledge of healthcare professional students at two Midwestern universities in the United States. BMC Med Educ 2019 Jul;19(1):242.

- 30. Lucas Ramanathan P, Baldesberger N, Dietrich LG, Speranza C, Lüthy A, Buhl A, et al. Health care professionals’ interest in vaccination training in Switzerland: a quantitative survey. Int J Public Health 2022 Nov;67:1604495.