Immunoglobulin A vasculitis (IgAV) is a self-limiting disease systemic, non-granulomatous, and autoimmune complex of small vessel vasculitis, with multiorgan involvement.1 Though it can occur at any age, it is most frequently seen in children. IgAV is the most common systemic vasculitis in childhood, with an incidence of approximately 20 per 100 000 children.2,3

The etiology of IgAV is unclear, but it is generally associated with infections, medications, vaccinations, cancers, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, and autoimmune diseases such as familial Mediterranean fever.4 IgAV is characterized by a classic tetrad of nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura, arthritis or arthralgias, and gastrointestinal and renal involvement, but rarely involves the lungs, central nervous system, or genitourinary tract.5

We report a case of IgAV diagnosed in a young girl who had recovered from a recent COVID-19 infection. She was treated initially with steroids, which led to dependency, and later with azathioprine, leading to complete remission.

Case Report

A 14-year-old girl with known chronic eczema, was admitted to our tertiary hospital with painless hematuria, high blood pressure, and purpuric skin rash. The rash started over her lower limbs and then progressed to the abdomen and upper limbs. It was associated with bilateral ankle pain and swelling, abdominal pain, and inability to walk. She also had developed hair loss and oral ulcers, but there were no genital ulcers. She also reported having irregular menstruation for 15 days. All these symptoms began following a bout of COVID-19 infection, which she had contracted eight weeks before the current presentation.

Clinical examination revealed a young girl with morbid obesity, a body mass index of 45 kg/m², and relatively high blood pressure (130/80) for her age. She was afebrile and had active, palpable purpuric erythematous lesions on her thighs, abdomen, arms, and forearms. She also had tender and swollen ankles, wrists, and shoulder joints, with malar

flush [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Active purpuric erythematous lesion on the leg. (a) Acute phase of polymorphic Gutate non-blanching erythematous purpuric lesions along with large dusky purpuric lesions with hemorrhagic centers. (b) Healing phase with crusted and fading purpuric lesions, along with others that have healed with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Figure 1: Active purpuric erythematous lesion on the leg. (a) Acute phase of polymorphic Gutate non-blanching erythematous purpuric lesions along with large dusky purpuric lesions with hemorrhagic centers. (b) Healing phase with crusted and fading purpuric lesions, along with others that have healed with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Laboratory investigations revealed a total leukocyte count within the upper normal range level and a high urinary red blood cell count of > 60 cells/uL, but all remaining investigations were normal including virology, immunology, and inflammatory markers [Table 1].

Table 1: Results of laboratory tests on admission.

|

Hemoglobin, g/dL

|

14

|

11.5–15.5

|

|

Total leukocytes, × 103/μL

|

10

|

2.2–10

|

|

Platelets, × 109/μL

|

419

|

150–450

|

|

International normalized ratio

|

0.95

|

0.8–1.0

|

|

Serum creatinine, umol/L

|

58

|

53–97.2

|

|

Serum urea, mmol/L

|

3.6

|

2.1–8.5

|

|

Urine protein-creatinine ratio, mg/mmol

|

6.9

|

< 20.0

|

|

Urine red blood cells, cells/uL

|

> 60

|

< 2.0

|

|

Albumin, g/L

|

36

|

34–50

|

|

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h

|

17

|

2–30

|

|

C-reactive protein, mg/L

|

5

|

< 10

|

|

Complement level C3, mg/L

|

1927

|

850–1600

|

|

Complement level C4, mg/L

|

335

|

120–360

|

|

Antinuclear antibody

|

Negative

|

≤ 1:80

|

|

Anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, AU/mL

|

Nonreactive

|

< 19

|

|

Immunoglobulin A serum, mg/dL

|

Not available

|

> 368

|

|

HIV 1 and 2 antibodies

|

Nonreactive

|

Not detected

|

|

Hepatitis B surface antigen, log IU/mL

|

0.32 nonreactive ratio

|

1–9

|

|

Anti-hepatitis C virus Abs, log IU/mL

|

Nonreactive

|

1–8

|

|

Thyroid stimulating hormone, mIU/L

|

2.8

|

0.4–4

|

|

Free T4, pmol/L

|

14

|

11–18

|

|

Glycated hemoglobin, %

|

5.4

|

< 6.0

|

The patient was put on steroid treatment (prednisolone 60 mg/day) along with lisinopril (5 mg/day) for two weeks. However, once her condition improved, the family discontinued the medications.

One month later, she was seen by a dermatologist who took skin punch biopsies for histopathological examination. Its findings revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, consistent with IgAV with no dysplasia or malignancy. The oral prednisone (60 mg/day) treatment was restarted. Within one month, there was a dramatic response, but when over the subsequent two months, the steroid dosage was reduced to < 15 mg daily, she began to experience relapses.

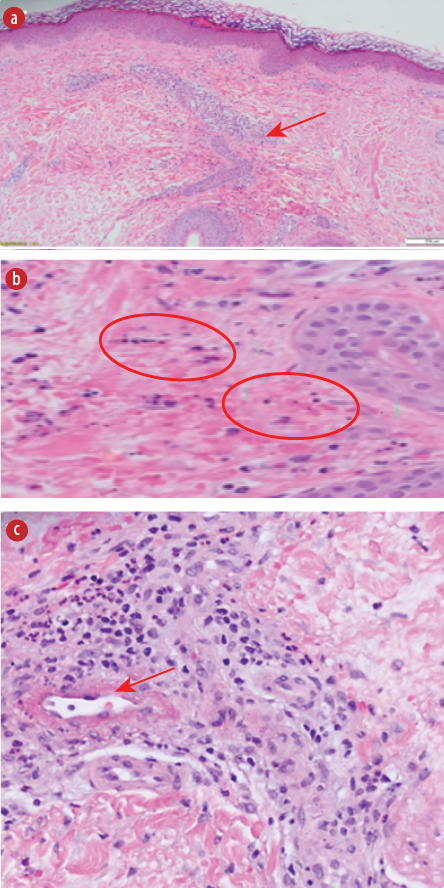

The post-relapse skin punch biopsy findings in the hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides are shown in Figure 2. It shows the histopathological changes in hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides of IgAV. While the immunofluorescence findings revealed superficial dermal vessels with positive staining for IgA++ and C3++, the results for IgG and IgM were negative.

Figure 2: Histopathological findings from the skin punch biopsy taken after several relapses. (a) Superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. (b) Extravasation of red blood cells and leukocytoclasia (nuclear dust). (c) Fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel.

Figure 2: Histopathological findings from the skin punch biopsy taken after several relapses. (a) Superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. (b) Extravasation of red blood cells and leukocytoclasia (nuclear dust). (c) Fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel.

Over the next three months, with tapering of steroid dose, once again, the patient developed frequent relapses of skin eruption and arthralgia. Hence, azathioprine 100 mg per day was started as a steroid-sparing agent along with the gradual withdrawal of steroids over the next three months when no relapses occurred. During the next six months of the follow-up period, the patient continued to take azathioprine 100 mg per day and achieved complete remission without any recurrence.

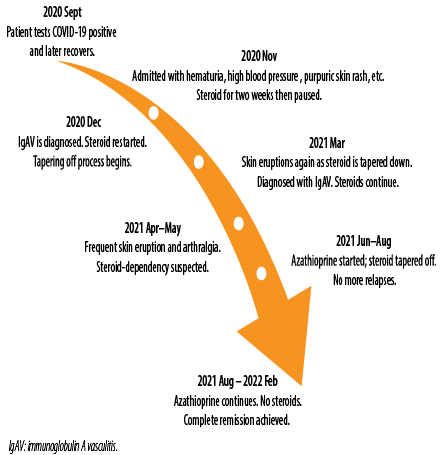

Figure 3 summarizes the timeline of the current case events from the initial development of IgAV post-COVID-19 infection till complete remission.

Figure 3: Timeline of the events until complete remission.

Figure 3: Timeline of the events until complete remission.

Discussion

COVID-19 is known to cause vasculitis-like syndromes, as seen in our patient, as reported in previously published cases listed in Table 2.6–12

Table 2: Summary of published cases of immunoglobulin A vasculitis following COVID-19.

|

Suso et al6

|

78

|

male

|

5 weeks later

|

Skin; nephritis

|

Steroid pulse and Rituximab

|

|

Hoskins et al7

|

2

|

male

|

Same time

|

Skin; abdominal pain

|

Intravenous steroid

|

|

Allez et al8

|

24

|

male

|

unknown

|

Skin; abdominal pain

|

Methylprednisolone 0.8 mg/day

|

|

Sandhu et al9

|

22

|

male

|

Same time

|

Skin; nephritis

|

Prednisolone 1 mg/kg

|

|

AlGhoozi et al10

|

4

|

male

|

37 days later

|

Skin

|

Not stated

|

|

Jacobi et al11

|

3

|

male

|

Same time

|

Skin; abdominal pain

|

Antibiotics

|

|

Li et al12

|

30

|

male

|

Same time

|

Skin; nephritis

|

Losartan 25 mg following

prednisolone 40 mg for 7 days

|

The European League Against Rheumatism, Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization, and Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (EULAR/PRINTO/PRES) collaboratively published in 2010, the following classification criteria for childhood vasculitides, including IgAV: purpura or petechiae and one of the following four criteria: abdominal discomfort, arthritis or arthralgia, kidney association, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with predominant IgA deposits, or proliferative glomerulonephritis with predominant IgA deposits (sensitivity 100%; specificity 87%).13 Our patient had all these characteristics.

As IgAV is usually diagnosed clinically, laboratory tests are often not considered essential and skin biopsies are rarely taken.14 However, chronic or recurrent IgAV symptoms should always raise concern for alternative causes of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, such as anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated vasculitis or systemic

lupus erythematosus.15,16

To investigate the several relapses in our patient, various laboratory tests were conducted, all of which came back negative. Blood results were also within normal levels. Therefore, we obtained a skin biopsy, which revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving the skin (palpable purpura).

Earlier studies performed in 2004 and 2006 (including an eight-year follow-up) showed similar results as ours, with corticosteroids providing no long-term benefits.17–19 Renal manifestations such as hematuria and proteinuria, were not resolved after 28 days of corticosteroid treatment but were reduced in comparison with placebo. At the six-month follow-up, the study found that 61% of patients had resolved kidney manifestations compared with 34% of placebo group. This study recommended corticosteroids for patients older than six years with mild kidney manifestations.17 The study also found statistically significant results regarding the treatment of extra-renal symptoms. Joint pain and abdominal involvements were reported with less frequency among people taking corticosteroid treatment compared to placebo. There was no difference between the groups in terms of skin manifestations.18,19

Our patient suffered several relapses while she was on steroids alone. Hence, azathioprine was added along with the steroid. A clinical and histopathological study by Foster et al,20 found that azathioprine therapy with corticosteroids had a therapeutic effect on IgA nephritis cases. In steroid-dependent patients, such cases could be managed by tapering steroids within three months and azathioprine continued as monotherapy for six months with minimal relapses or adverse events. This approach is similar to the management of inflammatory bowel disease.21,22

Conclusion

IgAV is typically self-limiting, therefore; our patient’s unusual relapses while on steroid therapy might be attributable to her history of COVID-19. We found azathioprine to be an effective therapeutic agent as it was curative while facilitating the gradual extinction of our patient’s steroid dependence.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Patient consent was obtained for the publication of this case report.

references

- 1. Audemard-Verger A, Pillebout E, Guillevin L, Thervet E, Terrier B. IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Shönlein purpura) in adults: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Autoimmun Rev 2015 Jul;14(7):579-585.

- 2.WWeiss PF. Pediatric vasculitis. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012 Apr;59(2):407-423.

- 3.GGardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, Southwood TR. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet 2002 Oct;360(9341):1197-1202.

- 4. Chen KR, Carlson JA. Clinical approach to cutaneous vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008;9(2):71-92.

- 5. Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Dig Dis Sci 2008 Aug;53(8):2011-2019.

- 6. Suso AS, Mon C, Oñate Alonso I, Galindo Romo K, Juarez RC, Ramírez CL, et al. IgA vasculitis with nephritis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int Rep 2020 Nov;5(11):2074-2078.

- 7. Hoskins B, Keeven N, Dang M, Keller E, Nagpal R. A child with COVID-19 and immunoglobulin a vasculitis. Pediatr Ann 2021 Jan;50(1):e44-e48.

- 8. Allez M, Denis B, Bouaziz JD, Battistella M, Zagdanski AM, Bayart J, et al. COVID-19-related IgA vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020 Nov;72(11):1952-1953.

- 9. Sandhu S, Chand S, Bhatnagar A, Dabas R, Bhat S, Kumar H, et al. Possible association between IgA vasculitis and COVID-19. Dermatol Ther 2021 Jan;34(1):e14551.

- 10. AlGhoozi DA, AlKhayyat HM. A child with Henoch-Schonlein purpura secondary to a COVID-19 infection. BMJ Case Rep 2021 Jan;14(1):e239910.

- 11. Jacobi M, Lancrei HM, Brosh-Nissimov T, Yeshayahu Y. Purpurona: a novel report of COVID-19-related Henoch-Schonlein purpura in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2021 Feb;40(2):e93-e94.

- 12. Li NL, Papini AB, Shao T, Girard L. Immunoglobulin-a vasculitis with renal involvement in a patient with COVID-19: a case report and review of acute kidney injury related to SARS-CoV-2. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2021 Feb;8:2054358121991684.

- 13. Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, Bakkaloglu A, Herlin T, Brik R, et al; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO). EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis 2010 May;69(5):798-806.

- 14. Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, Bagga A, Barron K, Davin JC, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis 2006 Jul;65(7):936-941.

- 15. Wright AC, Gibson LE, Davis DM. Cutaneous manifestations of pediatric granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a clinicopathologic and immunopathologic analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015 May;72(5):859-867.

- 16. Ramos-Casals M, Nardi N, Lagrutta M, Brito-Zerón P, Bové A, Delgado G, et al. Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence and clinical characteristics in 670 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006 Mar;85(2):95-104.

- 17. Weiss PF, Feinstein JA, Luan X, Burnham JM, Feudtner C. Effects of corticosteroid on Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2007 Nov;120(5):1079-1087.

- 18. Dudley J, Smith G, Llewelyn-Edwards A, Bayliss K, Pike K, Tizard J. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine whether steroids reduce the incidence and severity of nephropathy in Henoch-Schonlein Purpura (HSP). Arch Dis Child 2013 Oct;98(10):756-763.

- 19. Jauhola O, Ronkainen J, Autio-Harmainen H, Koskimies O, Ala-Houhala M, Arikoski P, et al. Cyclosporine A vs. methylprednisolone for Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: a randomized trial. Pediatr Nephrol 2011 Dec;26(12):2159-2166.

- 20. Foster BJ, Bernard C, Drummond KN, Sharma AK. Effective therapy for severe Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis with prednisone and azathioprine: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Pediatr 2000 Mar;136(3):370-375.

- 21. Sood A, Midha V, Sood N, Bansal M. Long term results of use of azathioprine in patients with ulcerative colitis in India. World J Gastroenterol 2006 Dec;12(45):7332-7336.

- 22. Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP; IBD Section, British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2004 Sep;53(Suppl 5)(Suppl 5):V1-V16.