Hypoglycemia, mainly associated with diabetes mellitus (DM), is a leading cause for emergency department (ED) visits worldwide.1 The expected global increase in DM prevalence (from 463 million cases in 2019 to 578 million by 2030) is likely to proportionately elevate the incidence of hypoglycemia as well.1,2

The American Diabetes Association defines hypoglycemia as an abnormally low random blood sugar (RBS) level of ≤ 3.9 mmol/L (70 mg/dL).3 However, this threshold can vary slightly among patients depending on their clinical conditions. For instance, patients with poorly controlled DM and younger people with newly diagnosed DM may experience symptoms of hypoglycemia at a higher glucose levels than patients with tightly controlled DM and those with a chronic history of the disease.4–6

Hypoglycemia primarily occurs in DM patients who receive insulin or sulfonylurea therapy, often due to incorrect dosing or erratic meal timing.7 Symptoms of hypoglycemia are categorized to neurogenic, characterized by a rapid drop in blood glucose levels; and neuroglycopenic, where there is insufficient glucose availability in the central nervous system. The symptoms of neurogenic hypoglycemia are usually sweating, palpitation, tremor, anxiety, and paresthesia. Neuroglycopenic hypoglycemia symptoms manifest as impaired cognition, seizures, and coma.2

The severity of hypoglycemic episodes can range from mild nausea to profound neurological impairment. The typical intervention is to attempt to raise the blood glucose level by administering glucose or dextrose.7 Although glucagon is considered the first line treatment for patients with severe hypoglycemia,8 it remains underappreciated and underused.6 Glucagon is a polypeptide hormone produced by the alpha cells of the pancreas. It binds to glucagon receptors found throughout the body. This activates G-protein-coupled receptors, which in turn activates adenylate cyclase, resulting in an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels. This process activates glycogenolysis and glucogenesis, causing an increase in blood glucose levels.2,9,10 The recent availability of novel glucagon formulations, such as intranasal and ready-to-use liquid glucagon, is expected to enhance its accessibility and ease of use in emergencies.8

This study aimed to identify the incidence of hypoglycemia and its causes in the ED at a tertiary care hospital in Oman before the COVID-19 pandemic. The knowledge of the pre-pandemic hypoglycemia trends may serve as a baseline for comparison with the trends at the years during and after the pandemic. We have also investigated hypoglycemia treatment approaches and the use of glucagon as a treatment option. This may also serve as a baseline for comparison to its present and future use, particularly with the current availability of novel glucagon formulations.

Methods

This cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted on all adult patients admitted with hypoglycemia to the ED at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) in Muscat, Oman. Inclusion criteria comprised: age ≥ 15 years at the time of first presentation at SQUH ED with RBS ≤ 3.9 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) during the period from January 2010 to January 2017. Patient data were retrieved from the TrakCare database of SQUH. Patient data extracted included demographic characteristics, presenting symptoms, suspected etiologies of hypoglycemia, treatment provided, and mortality cases. To assess the overall hypoglycemia, the incidence was expressed as the number of hypoglycemia cases per 10 000 ED visits. The total number of ED visits during the study period was considered as the denominator in the calculation, allowing for a standardized measure of incidence over time. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical and Research Ethics Committee at SQU (MERC# 1612).

The extracted data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics for continuous and certain categorical variables were presented as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and presented as numbers and percentages. A p-value ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

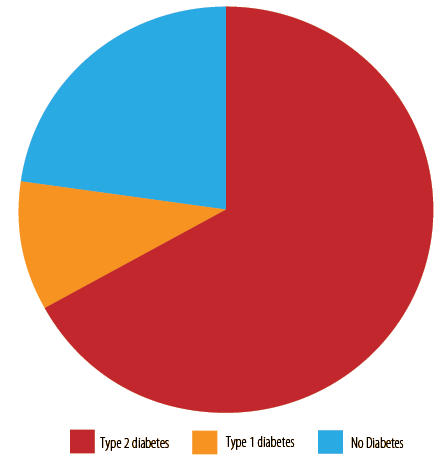

We reviewed the records of 242 hypoglycemic patients, 116 (47.9%) males and 126 (52.1%) females. Their mean RBS at presentation was 2.3 ± 0.6 mmol/L. The majority were DM patients (187; 77.3%), with type 2 diabetes being the more prevalent (162; 66.9%) than type 1 diabetes (25; 10.3%). A total of 55 (22.7%) patients were non-diabetic. The mean RBS for DM patients was 2.2 ± 0.6 mmol/L and 2.4 ± 0.7 for non-diabetics.

The proportion of non-smokers was significantly higher among DM patients than non-diabetic patients (92.5% vs. 81.8%; p = 0.011). In addition, 97.3% of diabetics were teetotalers compared to 87.4% of non-diabetics (p = 0.022). The other differences were nonsignificant [Table 1 and Figure 1].

Table 1: Hypoglycemic patients’ demography and diabetic status.

|

Sex, male

|

116 (47.9)

|

85 (45.5)

|

31 (56.4)

|

0.169

|

|

Married

|

223 (92.1)

|

175 (93.6)

|

48 (87.3)

|

0.153

|

|

Abnormal BMI, kg/m2 (n = 127) (≥ 25 and < 18.5)

|

75 (31.0)

|

61 (32.6)

|

14 (25.5)

|

1.000

|

|

Nonsmoker

|

218 (90.1)

|

173 (92.5)

|

45 (81.8)

|

0.011*

|

*Significant; BMI: body mass index.

Figure 1: The diabetic status of the hypoglycemic patients (N = 242).

Figure 1: The diabetic status of the hypoglycemic patients (N = 242).

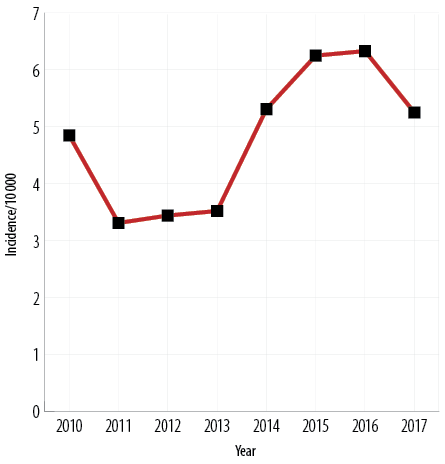

The yearly incidence of hypoglycemia cases varied considerably during the study period, with a slight overall increase, as illustrated by Figure 2. Table 2 presents the study cohort’s presenting symptoms, comorbidities, and treatments provided, stratified according to the patients' diabetic status.

Figure 2: Incidence of hypoglycemia cases per 10 000 total visits to the emergency department

Figure 2: Incidence of hypoglycemia cases per 10 000 total visits to the emergency department

(N = 242).

Table 2: Association between diabetic status and presenting symptoms, suspected etiology, and emergency interventions given.

|

Symptoms

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body temperature

|

69 (28.5)

|

52 (27.8)

|

17 (30.9)

|

0.734

|

|

Heart rate

|

67 (27.7)

|

44 (23.5)

|

23 (41.8)

|

0.010*

|

|

Systolic blood pressure

|

175 (72.3)

|

145 (77.5)

|

30 (54.5)

|

0.002*

|

|

Diastolic blood pressure

|

118 (48.8)

|

94 (50.3)

|

24 (43.6)

|

0.444

|

|

Hypoglycemic coma

|

2 (0.8)

|

2 (1.1)

|

-

|

1.000

|

|

Fever

|

20 (8.3)

|

13 (7.0)

|

7 (12.7)

|

0.175

|

|

Neutropenia

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Electrolyte imbalance

|

6 (2.5)

|

5 (2.7)

|

1 (1.8)

|

1.000

|

|

Gastrointestinal symptoms

|

36 (14.9)

|

23 (12.3)

|

13 (23.6)

|

0.052

|

|

Anemia

|

2 (0.8)

|

1 (0.5)

|

1 (1.8)

|

0.407

|

|

Altered INR/coagulation/bleeding

|

2 (0.8)

|

2 (1.1)

|

-

|

1.000

|

|

Sweating

|

23 (9.5)

|

19 (10.2)

|

4 (7.3)

|

0.610

|

|

Drowsiness

|

43 (17.8)

|

30 (16.0)

|

13 (23.6)

|

0.231

|

|

Palpitations

|

4 (1.7)

|

3 (1.6)

|

1 (1.8)

|

1.000

|

|

Seizures

|

3 (1.2)

|

1 (0.5)

|

2 (3.6)

|

0.132

|

|

Unconsciousness

|

17 (7.0)

|

15 (8.0)

|

2 (3.6)

|

0.476

|

|

Motor deficit

|

26 (10.7)

|

20 (10.7)

|

6 (10.9)

|

1.000

|

|

Etiology

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liver disease

|

19 (7.9)

|

11 (6.0)

|

8 (14.5)

|

0.049*

|

|

Liver cirrhosis

|

10 (4.1)

|

4 (2.1)

|

6 (10.9)

|

0.011*

|

|

Acute renal dysfunction

|

7 (2.9)

|

7 (3.7)

|

-

|

0.357

|

|

Renal dysfunction

|

62 (25.6)

|

51 (27.4)

|

11 (20.0)

|

0.295

|

|

Malignancies

|

12 (5.0)

|

6 (3.2)

|

6 (10.9)

|

0.034*

|

|

Poor oral intake

|

57 (23.6)

|

43 (23.0)

|

14 (25.5)

|

0.723

|

|

Drugs/toxins

|

5 (2.1)

|

0 (0.0)

|

5 (9.1)

|

0.001*

|

|

Infection/sepsis

|

37 (15.3)

|

23 (12.3)

|

14 (25.5)

|

0.031*

|

|

Cerebrovascular disease

|

152 (62.8)

|

131 (70.1)

|

21 (38.2)

|

< 0.001*

|

|

Uremia

|

3 (1.3)

|

3 (1.6)

|

-

|

1.000

|

|

Urinary tract infection

|

11 (4.5)

|

9 (4.8)

|

2 (3.6)

|

1.000

|

|

Pneumonia

|

11 (4.5)

|

8 (4.3)

|

3 (5.5)

|

0.719

|

|

Intervention received at ED

|

|

|

|

|

|

Juice or honey

|

58 (24.0)

|

46 (24.6)

|

12 (21.8)

|

0.722

|

|

Glucagon

|

1 (0.4)

|

0 (0.0)

|

1 (1.8)

|

0.230

|

|

Glucose gel

|

4 (1.7)

|

3 (1.6)

|

1 (1.8)

|

1.000

|

|

Bolus glucose

|

23 (9.6)

|

20 (10.7)

|

3 (5.5)

|

0.303

|

|

Intravenous dextrose

|

211 (87.2)

|

168 (89.8)

|

43 (78.2)

|

0.015*

|

|

Outcome

|

|

|

|

|

*Significant. ED: emergency department; INR: international normalized ratio.

The most prevalent presenting symptom of hypoglycemia was abnormal blood pressure, both systolic (175; 72.3%) and diastolic (118; 48.8%). Systolic abnormality was significantly more prevalent among DM patients (145; 77.5%) compared to non-diabetic (n = 30; 54.5%) (p = 0.002) [Table. 2]. In contrast, abnormal heart rate was significantly higher among non-diabetic patients (23; 41.8% vs. 44; 23.5%) (p = 0.010) [Table 2].

The etiology of hypoglycemia in the patients admitted to the ER was determined based on their preexisting diseases or comorbidities. The most frequently observed hypoglycemia-linked etiology was cerebrovascular disease (152; 62.8%), whose prevalence was significantly higher among diabetic patients (131, 70.1% vs. 21, 38.2%; p < 0.001), followed by renal dysfunction (62; 25.6%) and poor oral intake (57; 23.6%), albeit without significant intergroup differences [Table 2].

A few less-prevalent etiologies deserve mention due to significant differences between the groups. Non-diabetics were significantly more likely to present with liver disease (8, 4.5% vs. 11/, 5.9%; p = 0.049), liver cirrhosis (6, 10.9% vs. 4, 2.1%; p = 0.011), malignancies (6, 10.9% vs. 6, 3.2%; p = 0.034), drugs/toxins (5, 9.1% vs. 0, 0.0%; p = 0.001), and infection/sepsis (14, 25.5% vs. 23, 12.3%; p = 0.031), [Table 2].

Regarding the ED interventions for hypoglycemia, the majority received intravenous dextrose (211; 87.2%). Others were orally given fruit juice or honey (58; 24.0%), bolus glucose (23; 9.5%), or glucose gel (4, 1.7%). Glucagon was the least-used intervention, administered to only one (0.4%) patient. Additionally, intravenous dextrose was used significantly more for DM patients (168, 89.8%) than for patients without diabetes (43, 78.2%); p = 0.015 [Table 2].

Although no mortality was attributed to hypoglycemia, four deaths were reported due to pre-existing comorbidities unrelated to the hypoglycemia: metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, sepsis septic shock, hepatitis C liver cirrhosis, and sepsis and low ejection fraction heart failure.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the incidence of hypoglycemia in ED and its presenting symptoms, causes, and treatment approaches before the COVID-19 pandemic. Hypoglycemia has been linked to a mortality rate of 2–6% in patients with type 1 diabetes, and in the pandemic era from 2020–2023, their risk of hypoglycemia increased.11–13 This increase was attributed to several factors, such as limited access to healthcare services and the use of certain medications such as hydroxychloroquine.14 Moreover, the COVID-19 virus effects on the immune system could trigger episodes of hypoglycemia.15 Therefore, results from this study will serve as a baseline for comparison with the hypoglycemia trends in years during and after the pandemic.

Hypoglycemia is associated with various heart rate abnormalities, including ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmias, and bradycardia.16,17 The low blood pressure during a hypoglycemic event is compensated with the secretion of epinephrine, resulting in tachycardia, the body’s attempt to supply more glucose to tissues.17 Moreover, the low blood pressure during a hypoglycemic episode can disrupt the heart’s electrical activity, resulting in atrial fibrillation or ventricular arrhythmias.18 In severe cases of hypoglycemia, due to the limited glucose delivery to the vital organs such as the brain, the heart’s ability to sustain a normal rate becomes impaired causing bradycardia.19

In our study cohort, abnormal heart rate was significantly higher among non-diabetic patients, attributable to the significantly higher hypoglycemia-linked etiologies among them—liver disease, cirrhosis, malignancies, drugs/toxins, and infection/sepsis—compared to the diabetic patients. the prevalence of cerebrovascular diseases was significantly higher among DM patients, present independently from the hypoglycemia incidence. In DM patients, recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia pose a significant cardiovascular risk as a result of vascular damage.20,21 This is because each hypoglycemic event triggers a cascade of physiological changes, such as elevation in platelet aggregation and coagulation factors, as well as inducing inflammation, cumulatively impacting the vasculature.20,21

Intravenous dextrose was the most used treatment approach (87.2%), especially for DM patients. The management of hypoglycemia in the ED depends on the severity of the condition. Interventions may also include glucose in the form of juice, honey, or glucose gel for mild cases and intravenous dextrose and glucagon for severe cases.8,22

Glucagon was administered to only one (non-diabetic) patient in this cohort. The use of glucagon for hypoglycemia still remains limited despite its demonstrated effectiveness and safety in restoring blood glucose levels and consciousness.6 Unlike intravenous dextrose, glucagon can be administrated without healthcare workers, also can be administrated subcutaneously or intramuscularly,6 or through newer formulations. A 2020 study reported a success rate of 90.6% with self-administered nasal glucagon against 7.9% with injectable glucagon.23 The current availability of novel glucagon formulations such as nasal glucagon and liquid glucagon,8 as well as providing glucagon kits and educating parents and school nurses on its administration, is likely to aid in the future reduction of hypoglycemia incidence in the ED.

This study has a few limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study may have resulted in incomplete data. Second, the study was conducted in a single center, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other institutions in Oman. The study did not compare the effectiveness of different treatment modalities, which warrants further investigation. Finally, our findings did not reflect the hypoglycemia trends during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the study serves as a baseline for comparison with the latter periods.

Conclusion

This study presents the hypoglycemia trends at the ED before the COVID-19 pandemic, which may be used as a baseline for comparison with the trends during and after the pandemic in terms of incidence, etiologies, and management. Our study also revealed the need to promote increased usage of glucagon, especially for severe cases of hypoglycemia.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Kumar JG, Abhilash KP, Saya RP, Tadipaneni N, Bose JM. A retrospective study on epidemiology of hypoglycemia in emergency department. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2017;21(1):119-124.

- 2. Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2019 Nov;157:107843.

- 3. Workgroup on Hypoglycemia, American Diabetes Association. Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American diabetes association workgroup on hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2005 May;28(5):1245-1249.

- 4. Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003 Jun;26(6):1902-1912.

- 5. Zammitt NN, Frier BM. Hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiology, frequency, and effects of different treatment modalities. Diabetes Care 2005 Dec;28(12):2948-2961.

- 6. Kedia N. Treatment of severe diabetic hypoglycemia with glucagon: an underutilized therapeutic approach. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2011;4:337-346.

- 7. Nakhleh A, Shehadeh N. Hypoglycemia in diabetes: an update on pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention. World J Diabetes 2021 Dec;12(12):2036-2049.

- 8. Porcellati F, Di Mauro S, Mazzieri A, Scamporrino A, Filippello A, De Fano M, et al. Glucagon as a therapeutic approach to severe hypoglycemia: after 100 years, is it still the antidote of insulin? Biomolecules 2021 Aug;11(9):1281.

- 9. Venugopal SK, Sankar P, Jialal I. Physiology, glucagon. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL); 2023.

- 10. Evans DB. Modulation of cAMP: mechanism for positive inotropic action. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1986;8(Suppl 9):S22-S29.

- 11. Chen Y-J, Yang C-C, Huang L-C, Chen L, Hwu C-M. Increasing trend in emergency department visits for hypoglycemia from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Taiwan. Prim Care Diabetes 2015 Dec;9(6):490-496.

- 12. Cryer PE. Severe hypoglycemia predicts mortality in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012 Sep;35(9):1814-1816.

- 13. Shah K, Tiwaskar M, Chawla P, Kale M, Deshmane R, Sowani A. Hypoglycemia at the time of Covid-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14(5):1143-1146.

- 14. Cansu DÜ, Korkmaz C. Hypoglycaemia induced by hydroxychloroquine in a non-diabetic patient treated for RA. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008 Mar;47(3):378-379.

- 15. Sehemby MK, Lila AR, Sarathi V, Bandgar T. Insulin autoimmune hypoglycemia syndrome following coronavirus disease 2019 infection: a possible causal association. IJEM Case Reports 2023;1(1):5-8.

- 16. Andersen A, Jørgensen PG, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T. Hypoglycaemia and cardiac arrhythmias in diabetes. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2020 May;11:2042018820911803.

- 17. Frier BM, Schernthaner G, Heller SR. Hypoglycemia and cardiovascular risks. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl 2):S132-S137.

- 18. Sun DK, Zhang N, Liu Y, Qiu JC, Tse G, Li GP, et al. Dysglycemia and arrhythmias. World J Diabetes 2023 Aug;14(8):1163-1177.

- 19. Ormond AP. Bradycardia due to spontaneous hypoglycemia: report of a case. J Am Med Assoc 1936;106(20):1726-1728.

- 20. Saik OV, Klimontov VV. Hypoglycemia, vascular disease and cognitive dysfunction in diabetes: insights from text mining-based reconstruction and bioinformatics analysis of the gene networks. Int J Mol Sci 2021 Nov;22(22):12419.

- 21. Snell-Bergeon JK, Wadwa RP. Hypoglycemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Technol Ther 2012;14(Suppl 1):S51-S58.

- 22. Haymond MW, DuBose SN, Rickels MR, Wolpert H, Shah VN, Sherr JL, et al; T1D Exchange Mini-dose Glucagon Study Group. Efficacy and safety of mini-dose glucagon for treatment of nonsevere hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017 Aug;102(8):2994-3001.

- 23. Settles JA, Gerety GF, Spaepen E, Suico JG, Child CJ. Nasal glucagon delivery is more successful than injectable delivery: a simulated severe hypoglycemia rescue. Endocr Pract 2020 Apr;26(4):407-415.