Gigantomastia is a rare benign disorder characterized by excessive enlargement of the breast. There is no universal definition or classification for this condition, but the general consensus describes gigantomastia with a cutoff point of 1.5 kg per breast that requires reduction.1

An extensive study documented only a total of 115 gigantomastia cases reported between 1910–2006 and classified these as juvenile (49.6%), pregnancy-induced (35.7%), drug-induced, or idiopathic.2 With regards to juvenile gigantomastia, rare familial incidences have also been reported.3

Juvenile gigantomastia occurs with the onset of puberty shortly after thelarche.4 For young girls, this condition may lead to severe emotional trauma, reduced self-esteem, and social isolation.

We present a unique case of juvenile gigantomastia, which to our knowledge, is the first case to be reported from Bahrain. Two similar cases in girls aged 13 and 15 years were reported from Iraq.5 Two cases of gestational gigantomastia were reported from Saudi Arabia and the UAE,6,7 and one case of idiopathic gigantomastia from Tunisia.4

Case Report

A 10-year-old Bahraini girl presented to the emergency department with a 10-day history of progressive bilateral breast enlargement. The progression had accelerated over three days before the presentation, during which she was having her first menstrual cycle. She did not complain of any other physical symptoms, but she did have a depressed mood and reduced self-esteem. She had stopped attending school due to fear of social embarrassment. The onset of her thelarche was two months before presentation. The patient denied a history of taking any medication.

On physical examination, she appeared normal (body mass index = 18.85 kg/m2) except for her hypertrophic breasts. The right breast was much larger than the left [Figure 1]. There was no overlying skin discoloration or ulcerations and no nipple changes. On palpation, the breast tissue was soft and mildly tender. There were no palpable masses or axillary lymphadenopathy.

Figure 1: The patient’s breasts at presentation before surgery.

Figure 1: The patient’s breasts at presentation before surgery.

Breast sonography revealed increased fibroglandular breast tissue with an area of interstitial fluid, prominent vascularity, and dilated veins.

There was no evidence of focal masses, collections, ductal ectasia, or axillary lymphadenopathy. Laboratory assay for hormonal level yielded normal results [Table 1].

Table 1: Summary of hormonal test results.

|

Follicle-stimulating hormone

|

2.9 IU/L

|

0.2–3.8 (child)

3.3–11.3 (adult female)

|

|

Luteinizing hormone

|

2.2 IU/L

|

0.1–0.6 (child)

1.9–12.5 (follicular phase)

8.7–76.3 (midcycle peak)

0.5–16.9 (luteal phase)

|

|

Estradiol

|

435 pmol/L

|

72–530 (follicular phase)

234–1309 (ovulatory phase)

204–786 (luteal phase)

|

|

Prolactin

|

8.9 ng/mL

|

3.9–23.5 (children)

3.9–29.5 (adult female)

|

|

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

|

3.7 mIU/L

|

0.25–5

|

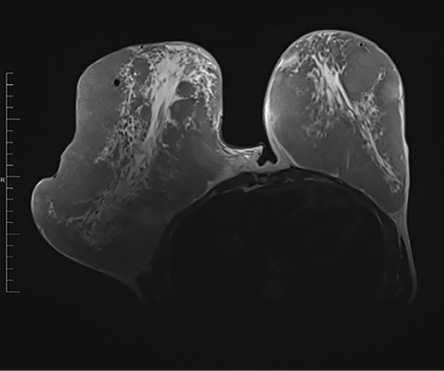

Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound results were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast revealed extremely high breast density with > 75% fibroglandular tissue, showing marked post-contrast enhancement, consistent with a diagnosis of juvenile breast hypertrophy [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Axial T2-weighted MRI of the chest showing a significant asymmetrical breast enlargement, more on the right along with extremely dense fibroglandular tissue bilaterally.

Figure 2: Axial T2-weighted MRI of the chest showing a significant asymmetrical breast enlargement, more on the right along with extremely dense fibroglandular tissue bilaterally.

During the evaluation, the patient was seen by different medical teams including the pediatric, general surgery, plastic surgery, and the primary team of pediatric endocrinology. Following the intensive workup and proper counseling, the patient underwent bilateral reduction mammoplasty with nipple-areola complex graft [Figure 3]. The excised right breast weighed 3800 g and the left weighed breast, 1076 g. The histopathological examination revealed a well-demarcated fibroepithelial tumor with a pericanalicular growth pattern [Figure 4]. The stroma was cellular and focally vascular variable hyalinization and focal myxoid change. There was variable stromal mitosis between three to 10 high-power fields, but no stromal cellular atypia or overgrowth. The histopathological features were consistent with the diagnosis of juvenile fibroadenoma.

Figure 3: The patient’s breasts one-month post bilateral mammoplasty with nipple-areola complex graft.

Figure 3: The patient’s breasts one-month post bilateral mammoplasty with nipple-areola complex graft.

Figure 4: Well-circumscribed fibroepithelial lesion with occasional dilated glands and homogeneous spindle cell stroma, hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification = 40 ×.

Figure 4: Well-circumscribed fibroepithelial lesion with occasional dilated glands and homogeneous spindle cell stroma, hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification = 40 ×.

After surgery, the patient had an unremarkable hospital course and was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. She underwent regular follow-ups at the general surgery and pediatric endocrinology clinics and continued to recover well. Six months later, she presented with a regrowth of the right breast that was to a lesser extent than the first time. No further surgical intervention was considered necessary. Two years later, the patient continues regular follow-up and stays asymptomatic.

Discussion

The current case of juvenile gigantomastia in a 10-year-old girl could be considered idiopathic as there was no identifiable cause for this rare condition. To our knowledge, this is the first such case reported in Gulf Cooperation Council. Since it was diagnosed during puberty, excessive hormonal release or increased hormonal sensitivity is suspected to be the cause (which also applies to gigantomastia during pregnancy).4 The treatment options for juvenile gigantomastia consist of medical and surgical management. Medical therapy includes but is not limited to tamoxifen, medroxyprogesterone, bromocriptine, and danazol, which can stop further growth of the breasts, but without reduction of the size or relief of the symptoms.3 It has limited outcomes and controversial long-term safety.3

In the present case, we opted for surgery as the breast enlargement was hugely disproportionate to the child’s age and body mass index. Equally important was to mitigate her severe emotional distress, low self-esteem, and potential social stigma. A bilateral reduction mammoplasty with nipple-areola complex graft was performed to reduce the breast volume while preserving the normal physiological breast function.

Though this approach preserved the native breast tissue, it carried the risk of recurrence.4 Therefore, mastectomy with implant reconstruction is often promoted as the definitive treatment.8 Our patient had experienced slight regrowth six months after the surgery, but the treatment outcome was satisfactory, and she remained asymptomatic to date. However, pregnancy can be a cause for recurrence.5

A meta-analysis of cases of virginal mammary hypertrophy revealed that subcutaneous mastectomy significantly reduced the risk of recurrence compared to the reduction mammaplasty.9 Moreover, in the four cases of juvenile gigantomastia reported by Baker et al,8 three patients experienced recurrence following reduction mammaplasty, one of which was induced by gestation. The patient who did not experience recurrence had undergone reduction mammaplasty using a free nipple graft.8 The same technique has been found in the UK to be superior to reduction mammoplasty in terms of lower risk of recurrence.10

Hoppe et al,9 advocated for the need of a multidisciplinary team to manage the diagnosed patients. We adopted this approach and the patient was seen by different disciplines. However, the input of the child and adolescent mental health team would have been of great value to alleviate the child’s psychological stress, which we strongly recommend for future cases.

Conclusion

The rarity of gigantomastia poses diagnostic and management challenges but should be considered in cases of abnormal puberty and pregnancy. Gigantomastia also has a severe psychological impact on the patients whether they are children or adolescents, and professional assessment and support are of paramount importance. We recommend having a common registry in the Gulf Cooperation Council for such rare conditions to help understand their natural history and prevalence.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother.

references

- 1. Dafydd H, Roehl KR, Phillips LG, Dancey A, Peart F, Shokrollahi K. Redefining gigantomastia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2011 Feb;64(2):160-163.

- 2. Dancey A, Khan M, Dawson J, Peart F. Gigantomastia–a classification and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61(5):493-502.

- 3. Bianchi de Aguiar B, Santos Silva R, Costa C, Castro-Correia C, Fontoura M. Juvenile breast hypertrophy. Endokrynol Pol 2020;71(2):202-203.

- 4. Benna M, Naser RB, Fertani Y, Ayadi MA, Bettaieb I, Chargui R, et al. Extreme idiopathic gigantomastia. Int J Res Med Sci 2018;6(5):1808-1811.

- 5. Fathallah ZF, Hameed JR. Juvenile gigantomastia, two cases treated by reduction mammoplasty with nipple areola comple graft. Medical Journal of Basrah University 2013;31(1):43-46.

- 6. Mahabbat N, Abdulla A, Alsufayan F, Alharbi A, Rafique A, Alqahtani M, et al. Gestational gigantomastia on a Saudi woman: a case report on surgical removal and reconstruction and management of complications, KFSH&RC. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020;77:157-160.

- 7. John MK, Rangwala TH. Gestational gigantomastia. BMJ Case Rep 2009;2009:bcr11.2008.1177.

- 8. Baker SB, Burkey BA, Thornton P, LaRossa D. Juvenile gigantomastia: presentation of four cases and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg 2001 May;46(5):517-525; discussion 525-526.

- 9. Hoppe IC, Patel PP, Singer-Granick CJ, Granick MS. Virginal mammary hypertrophy: a meta-analysis and treatment algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011 Jun;127(6):2224-2231.

- 10. Fiumara L, Gault DT, Nel MR, Lucas DN, Courtauld E. Massive bilateral breast reduction in an 11-year-old girl: 24% ablation of body weight. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009 Aug;62(8):e263-e266.