Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a prothrombotic condition defined by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, manifesting clinically as recurrent morbidity that tends to be associated with pregnancy and thromboembolic complications.1 The cutaneous manifestations of APS range from livedo reticularis to cutaneous necrosis. Ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) have been described in APS and may confuse diagnosis. We report a case of a middle-aged woman known to have APS and presented with pathergy following cannulation which led to non-healing ulcers that were relatively refractory to novel treatments. Our patient is being trialed on a new biologic agent proven to have success as described recently in the literature.1–3

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman was known to have primary APS. Her past medical history included glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD), uterine fibroids, and chronic iron deficiency anemia requiring frequent parenteral iron and blood transfusions. She presented to our emergency department in February 2022 looking very pale with easy fatiguability and palpitations. Blood tests revealed a low hemoglobin (Hb) level of 5 g/dL, a mean corpuscular volume of 54.9 femtoliters, and a mean corpuscular Hb of 18.10 pg/cell. The patient denied ingesting any fava beans or being exposed to any factor known to trigger hemolytic anemia due to her G6PD.

Urgent blood transfusion was requested but the cannulation site developed erythema followed by bulla formation. The cannula was reinserted at other sites where the same reaction occurred. In the following days, the cannulation sites developed ulcers, which later formed local abscesses. Figure 1 shows the post-cannulation lesions. Figure 2 shows advanced lesions with bulla formation around the areas of ulceration.

Figure 1: (a) Post-cannulation with superficial bulla. (b) The bulla has progressed to ulceration.

Figure 1: (a) Post-cannulation with superficial bulla. (b) The bulla has progressed to ulceration.

Figure 2: (a) Advanced lesions have formed with evidence of granulation. (b) The lesions after healing.

Figure 2: (a) Advanced lesions have formed with evidence of granulation. (b) The lesions after healing.

A surgical review was sought as the abscesses did not respond to empirical antibiotics but grew larger. Histological analysis of a soft tissue biopsy showed features consistent with acute necrotizing inflammation, abscess formation extending into deep margins, and fascia suggesting the possibility of necrotizing fasciitis. Soft-tissue ultrasound of the lesion showed localized collections and subcutaneous edema. Repeated ultrasound scans of the soft tissue showed the same collections. Given the above findings, a high suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis was considered by the surgical team, and urgent drainage and debridement were performed.

The surgical incisions had poor healing and progressively increased in size. Multiple pus swab cultures grew pseudomonas bacteria. The trials to insert cannulas for intravenous (IV) antibiotics again caused a formation of bulla followed by ulcerations. The patient refused any further trials, limiting her treatment to oral antibiotics and oral iron supplements.

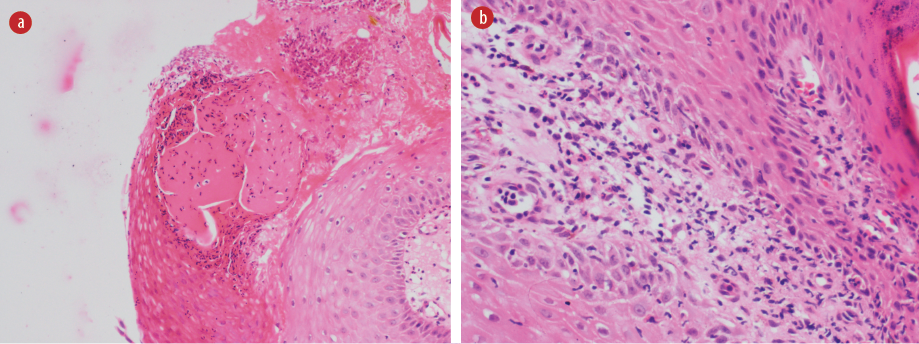

Because of these difficulties and prolonged stay of the patient in the hospital that exceeded three months, the rheumatology and dermatology teams were requested to be involved in her care. A punch biopsy was taken, which showed variable neutrophilic and mixed inflammatory infiltrate [Figure 3]. From the history of evolvement of the lesions, along with the chronicity and the development of new lesions with any minor or major traumas (cannulation and surgical debridements with incisions and drainage), a pathergy phenomenon was confirmed. The associated clinical and histological features of the lesions were met the 2018 Delphi consensus criteria for PG, and with the history of bulla formation, the patient was diagnosed with bullous pyoderma gangrenosum.

Figure 3: Histopathology slides showing intraepidermal bulla with inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis. (a) Intraepidermal pustular bulla, within the acanthotic epidermis, at the ulcer edge; (b) Scant dermis showing neutrophilic dermatoses with no evidence of vasculitis.

Figure 3: Histopathology slides showing intraepidermal bulla with inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis. (a) Intraepidermal pustular bulla, within the acanthotic epidermis, at the ulcer edge; (b) Scant dermis showing neutrophilic dermatoses with no evidence of vasculitis.

The tissue trauma was minimized by limiting the cannulation. Oral systemic steroids were started and later boosted to reach 0.7 mg/kg twice daily. As per the hospital guidelines, cyclosporine was added to the regimen as steroid-sparing immunosuppressant with occasional intralesional steroids for the new lesions and on sites of urgently needed cannulation. The patient was investigated thoroughly with ultrasound and computed tomography, but no indications of malignancy were found. Bone marrow aspiration to rule out any underlying lymphoproliferative disorder was not feasible as it caused a strong pathergy reaction, which led to the patient’s complete refusal of the procedure.

As only marginal response was achieved after six weeks of treatment, it was decided to administer an add-on medication, for which infliximab was the first option, but its administration was delayed because of the strong pathergy to cannulation and patient refusal. Therefore, we decided to start adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneously once every two weeks. The patient improved slowly over one month. To speed up the recovery process, adalimumab frequency was increased to once weekly. After a month, the patient showed significant improvement in terms of pain, ulcer depth, erythema, and general condition. The healed lesions looked atrophic with cribriform scarring.

The patient was discharged on just wound care and hydrocolloid dressing (DuoDerm®) every three to four days. The prognosis of slow healing over months and possible recurrence were explained to her. The surgical staff and caring teams were informed of the adverse consequences of the surgical incision, debridement, and cannula insertion, and were advised gentle superficial debridement for slough if required.

The patient failed to follow our instructions for regular wound care. She experienced a recurrence of pathergy reactions including deep ulcerations along with superadded infections in the abdomen and the upper and lower limbs. Her hemoglobin level declined to 6.8 g/dL. She was admitted again. A decision to change the biological agent from adalimumab to ustekinumab was made. The earlier treatment was repeated including systemic steroids, cyclosporin, intralesional steroids, daily dressing, frequent wound swabs, topical steroids, frequent monitoring of vital signs, and conducting routine investigations.

While we awaited the Ministry of Health’s approval for funding the newly elected biological agent, the patient was given anakinra 100 mg subcutaneously twice daily for a week then once daily for another week, but no improvement. However, upon initiating ustekinumab, she started to show a response except for the regular pseudomonal nosocomial infection with frequent abscess formation. This was managed by circularly injecting intralesional triamcinolone and hydrocortisone around the insertion point for a femoral venous catheter to avoid pathergy. This enabled us to give IV antibiotics, IV iron, and blood transfusions. Systemic steroids were tapered slowly and she was put on a maintenance dose of colchicine 500 mg twice daily. The daily wound care included washing with 10% acetic acid to eradicate pseudomonas and draining all abscesses using small incisions and superficial debridement. Most of the patient’s lesions healed again, and she was discharged on regular wound care for the remaining ones.

Discussion

PG is a rare dermatological inflammatory condition triggered by dysfunctional neutrophils, therefore classified as neutrophilic dermatosis. The histological predominance of neutrophils in the lesions and the absence of any bacterial source for the inflammation were the indicative features. A PG lesion typically starts as a pustule or a blister, often triggered by skin injury (the pathergic response). The lesion then progresses to form painful ulcers with undermined, violet-colored borders. Subtypes of PG include bullous, ulcerative, pustular, and vegetative. The bullous form is characterized by rapidly spreading painful superficial blisters that break down to form ulcers. It commonly involves the upper extremities and trunk and is linked to myeloproliferative disorders. Ulcerative PG is usually seen on the lower extremity at the site of skin trauma and starts as non-erythematous pustules that progress to form an ulcer. The pustular form begins with a painful erythematous pustule with an erythematous base. Finally, the vegetative type starts with an ulcer that could form sinus tracts. It is reported to respond well to treatment.4,5

PG is diagnosed clinically by its appearance and the severe associated pain. The 2018 Delphi consensus is a diagnostic tool for this condition [Box 1].6

Box 1: Diagnostic criteria for pyoderma gangrenosum. (2018 Delphi consensus).6

Because of the pre-existing APS in our patient, we considered the differentials listed in Box 2.7 However, most of these were ruled out by the pathergy criteria and the investigations conducted.

Box 2: Differential diagnosis for pyoderma gangrenosum.7

There is evidence for a strong link between PG and systematic diseases, with more than 50% of PG cases having underlying systematic disorders. This association with systematic diseases supports the autoinflammatory speculation and the role of innate immunity in the pathogenesis of PG. Idiopathic PG also has autoinflammatory features shown by the good response to systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Recent literature has shown relationships between PG and several disorders including inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, and hematological malignancies, and a rare association with systemic lupus erythematosus. However, there are only a few PG cases described in association with APS.4,5

Among the most recent cases of PG with APS reported in the literature is a 39-year-old man who presented with necrotic erosive lesions on his legs.8 Lab investigations revealed high anti-cardiolipin, anti-beta glycoprotein, and detectable lupus anticoagulant. The authors suggest that the pathogenesis of PG-like cutaneous ulcers may be related to abnormalities in the coagulation\fibrinolysis pathways in the APS.8 In another recent case, a 35-year-old woman presented with a non-healing ulcer for three months and was incidentally found to have APS despite having no previous manifestation.9

These cases, though rare, suggested that clinicians should consider APS for first-time presentation with PG-like skin lesions. Although PG has never been described as a cutaneous manifestation of APS, the ulcerations seen are deep, painful, and located above the malleoli. Researchers investigated lower extremity ulcerations of a group of APS patients and found features of PG in 15% of the cases. Those were treated successfully with immunosuppressive therapy (azathioprine or cyclosporine). This might suggest that PG could be overlooked in APS and is a call for more research on PG in APS.10

General measures in managing PG include local wound care with frequent cleansing and dressing that preferably provides a moist non-adherent environment for the lesions. It is also essential to avoid pathergic phenomena either by trauma or any substances applied to the skin. Surgical interventions should be limited to superficial gentle debridement.7,11

The first-line management of limited PG involves topical or intralesional corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic corticosteroids may be required if the lesions are extensive. Systemic cyclosporine is used as a first-line substitute if steroid is not tolerated or is added as an adjunct therapy with steroids.7,12 Biological and conventional immunosuppressive agents and antibiotics are considered second-line PG therapies for patients who have not responded to the first line management. Biological agents such as infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab, and golimumab have been used, and patients exhibit improvement dramatically when combined with other systemic therapies. Conventional immunosuppressive agents such as mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and azathioprine have been used in PG treatment. In addition, antibiotics such as dapsone and minocycline also showed a role in treating some PG cases. Dapsone was avoided in the present case due to its risk of drug-induced hemolytic anemia in G6PD cases.

Research and trials have yielded successful management results with new agents such as ustekinumab, canakinumab, and anakinra.11–14 The successful treatment with ustekinumab was reported among six refractory PG patients in Australia, with no adverse reactions.3

Conclusion

This is the case of a known patient of APS who was diagnosed with pyoderma gangrenosum and successfully treated with ustekinumab. Our literature review identified studies suggesting a possible link between APS and PG and narrating APS cases with cutaneous manifestations with features of PG, but dermatologically uncategorized. Future research may shed more light on this rare combination of diseases.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

references

- 1. Sammaritano L R. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2020;34(1):101463.

- 2. Westerdahl JS, Nusbaum KB, Chung CG, Kaffenberger BH, Ortega-Loayza AG. Ustekinumab as adjuvant treatment for all pyoderma gangrenosum subtypes. J Dermatolog Treat 2022 May 19;33(4):2386-2390.

- 3. Allnutt KJ, Low ZM, Mar A. New Zealand dermatological society Inc. Annual scientific meeting Queenstown, New Zealand August 2017 Convener: Dr Paul JM Salmon. Australasian Journal of Dermatology 2017;58(4):332-340.

- 4. Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012 Jun;13(3):191-211.

- 5. Oakley A, Dhawan G. Pyoderma gangrenosum. 2015 [cited 2023 January 1]. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pyoderma-gangrenosum.

- 6. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, Fiorentino D, Callen JP, Wollina U, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154(4):461-466.

- 7. Schadt C. Pyoderma gangrenosum: pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis. 2023 [cited 2023 February 1]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pyoderma-gangrenosum-pathogenesis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis.

- 8. Takahashi K, Ikeda T, Yokohama K, Kawakami T. Cutaneous ulcer resembling pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. J Cutan Immunol Allergy 2021;4(1):17-18.

- 9. Mansoor CA. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum. Egyptian Journal of Dermatology and Venerology 2022;42(1):77-79.

- 10. Cañas CA, Durán CE, Bravo JC, Castaño DE, Tobón GJ. Leg ulcers in the antiphospholipid syndrome may be considered as a form of pyoderma gangrenosum and they respond favorably to treatment with immunosuppression and anticoagulation. Rheumatol Int 2010 Jul;30(9):1253-1257.

- 11. Jourabchi N, Lazarus GS. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Fitzpatrick’s dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. p. 613.

- 12. Fletcher J, Alhusayen R, Alavi A. Recent advances in managing and understanding pyoderma gangrenosum. F1000Res 2019;8:F1000.

- 13. Alonso-León T, Hernández-Ramírez HH, Fonte-Avalos V, Toussaint-Caire S, E Vega-Memije M, Lozano-Platonoff A. The great imitator with no diagnostic test: pyoderma gangrenosum. Int Wound J 2020 Dec;17(6):1774-1782.

- 14. Lebwohl M. Pyoderma gangrenosum. 2018 [cited 2022 December 13]. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pyoderma-gangrenosum/.