According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 74% of the total global deaths in 2019 were from non-communicable diseases of which ischemic heart disease and stroke were the leading causes.1 Such cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have multifactorial origins, consisting of both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.2 To lower CVD mortality, aggressive and comprehensive management of its risk factors, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking, are crucial.

Dyslipidemia plays a central role as the deranged levels of serum lipids leads to atherosclerotic changes in vessels, increasing the chances of a cardiovascular event.3 Dyslipidemias are collectively among the most commonly detected and treated chronic conditions. They are classically characterized by abnormal serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, or both, involving abnormal levels of related lipoprotein species.

The developed countries have managed to reduce the burden of dyslipidemia significantly through raising awareness, rigorous lipid testing, improving the availability of lipid-lowering medications, and developing regularly updated guidelines.3 According to Liu et al,3 the number of deaths due to the aforementioned events in North America halved from ≈ 200 000 in 1990 to ≈ 100 000 in 2019. The opposite trend was observed in South Asian countries where the number of deaths from atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) attributable to dyslipidemia doubled from ≈ 200 000 in 1990 to ≈ 400 000 in 2019.3 According to WHO, the number of deaths in Pakistan from ASCVD attributable to dyslipidemia increased from ≈ 29 000 in 2000 to ≈ 44 000 in 2019.4 Even in the absence of the known risk factors, South Asians are reported to be more prone to develop CVD at an earlier age even in the absence of traditional risk factors.5 Dyslipidemia pattern in the Western populations is mainly characterized by increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), while South Asians have significantly low levels of high DL-C and high levels of triglycerides.6

To our knowledge, no evidence-based guideline for the management of dyslipidemia has been developed specifically for the population of Pakistan. Adopting the guidelines of other countries/cultures for managing dyslipidemia in Pakistan is likely to be inappropriate due to the differences in our dietary patterns and food sources. Hence, the main aim of this study was to determine local food sources beneficial in certain coexistent diseases bearing in mind the poor economic status of most of the Pakistani population.

We sought to conduct a systematic review of the current local and international guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia to develop a detailed and extensive comparison of the nutritional recommendations, followed by a modified version of MyPlate. The secondary objective was to use these guidelines and data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), to establish basic dietary suggestions for nutritional management of dyslipidemia and the related comorbidities prevalent among the Pakistani population. Based on the aforementioned information, our clinical dietitians suggested Pakistani foods with similar nutritional value.

Methods

This systematic review employed the criteria included in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review. The protocol for this review was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (CRD42023414885).

The inclusion criteria were based on the definition of clinical practice guidelines provided by the Institute of Medicine’s 2011 definition:7 “Clinical Practice Guidelines are statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.” Hence, only those guidelines were included which had evidence-based statements meant for application in clinical practice as a standard of care for dyslipidemia, augmented management of dyslipidemia through risk stratification, screening and diagnosis and suggesting treatment option(s) for dyslipidemia and/or compare their advantages and disadvantages.

Guidelines written in languages other than English, older versions, guidelines that were gender-specific or focused on the pediatric population, or specifically focused on the management of a single disease were excluded.

This systematic review was conducted with search results from the databases of Pubmed, Scopus, and the International Guidelines Library. The search results acquired from these databases were tabulated in Microsoft Office 365 Excel. First, the duplicates were removed followed by the screening of titles, abstracts, and full text articles independently by two reviewers. Then, the screenings by the two reviewers were compared and any conflict was resolved by the judgment of a third reviewer. The guidelines were analyzed and compared based on their recommendations for non-pharmacological and pharmacological management of dyslipidemia with treatment goals.

To assess the quality and utility of the guidelines, the Mini-Checklist tool (MiChe, 2014)8 was used by two authors independently. This tool assesses the quality of the guidelines through eight different points including the manner of presentation, background and objectives, evidence review methodology, details of treatment approaches etc. on a three-level (1- ‘Yes,’ 2- ‘To some extent,’ 3- ‘No’) scale. The assessed eight criteria were then converted into an overall quality score on a 7-level scale in which guidelines with scores of 1–3 were labelled as high overall risk of bias while those which scored 5–7 were labelled as low overall risk of bias. The formula used to calculate the risk of bias was:8

Overall quality rating = ¾(nyes) + ⅜ (nto some extent) + 1

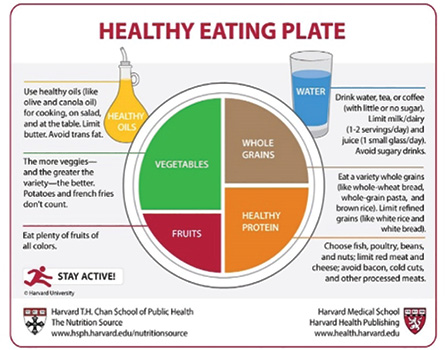

The USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion has developed a dietary advisory called ‘MyPlate’ to facilitate the public in organizing their dietary intake. We used the Healthy Eating Plate [Figure 1]9 as the original MyPlate created by Harvard Health Publishing Staff because it provides more specific guidance to consumers.

Figure 1: Healthy Eating Plate developed by Harvard Eating Plate. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/comparison-of-healthy-eating-plate-and-usda-myplate. © 2011, Harvard University.

Figure 1: Healthy Eating Plate developed by Harvard Eating Plate. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/comparison-of-healthy-eating-plate-and-usda-myplate. © 2011, Harvard University.

Results

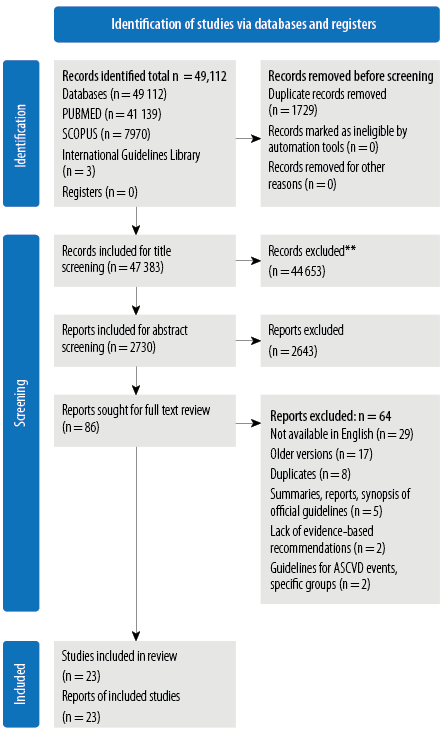

The search results of Pubmed, Scopus, and the International Guidelines Library are given in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Flowchart showing the process and the results of the systematic review on local and international guidelines for dyslipidemia.

Figure 2: Flowchart showing the process and the results of the systematic review on local and international guidelines for dyslipidemia.

Despite the different burdens of cholesterol in various countries, the treatment approaches do not have many differences. However, each guideline showcases significant variability in dietary patterns recommended for dyslipidemia. Most of the regions have strategies for primary and secondary prevention.10–17 Primary prevention strategies are applicable to individuals with documented dyslipidemia but with no history of any ASCVD event (such as myocardial infarction or stroke), while secondary prevention is employed for those with documented dyslipidemia and history of an atherosclerotic cardiovascular event. A brief regional comparison of the management approaches for dyslipidemia according to the guidelines is provided in Table 1. The summary column of Table 1 presents the recommendations of all the guidelines which were similar in

nutritional content.

Table 1: Comparison of recommended dietary patterns in different countries.

|

Mediterranean-style dietary pattern15–20

|

USA, Canada, India, Europe

|

Reduce fat and dairy products

Consume fish, lean meats, and skinless poultry

Reduce salt intake

Consume soluble fiber and sources of insoluble fiber (such as whole wheat)

Reduce total fat intake to 25–35% of total energy intake

Consume a high unsaturated fat/saturated fat ratio

Consume plant-based foods (fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and grains)

Consume extra virgin olive oil

|

Lipids:

Reduce intake of trans fats and saturated fats

Increase intake of MUFAs and PUFAs

Avoid high fat products like fried foods, bakery items, etc

Increase intake of extra virgin olive oil.

Carbohydrates:

Increase intake of fruits, nuts, grains, legumes and vegetables

Avoid products with high glycemic index like bakery products, foods with artificial sweeteners and refined carbohydrates, beverages, fruits juices, etc

Proteins:

Consume fish, lean meats, proteins from plant sources (lentils, whole grains)

Avoid processed meats and fatty meats.

Reduce intake of salt

Reduce intake of alcohol

Increase intake of plant sterols and dietary fiber

Non-dietary recommendations for dyslipidemia management:

Reduce weight by physical activity

Avoid smoking

Maintain adequate amount of sleep

Appropriate management of stress and mental health disorders

|

|

Dietary approaches to stop Hypertension dietary pattern16,19,20

|

India, UAE, Canada, Europe

|

Consume higher amounts of fruit, nonstarchy vegetables, nuts, legumes, fish, vegetable oils, yoghurt, and whole grains

Reduce intake of red and processed meats, foods higher in refined carbohydrates, and salt

|

|

Ketogenic dietary pattern20

|

India

|

Consume higher amounts of fat and protein

Reduce carbohydrate consumption to as low as 20−50 g daily

|

|

Macronutrient-targeted dietary pattern21,22

|

China, Japan

|

Consume carbohydrates that is 50−65% of total energy intake

Reduce lipid intake to < 20−30% of total energy intake

|

|

The American Heart Association dietary pattern14

|

USA

|

Consume a diet based on vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, and fish

Replace saturated fat with dietary monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats

Reduce intake of cholesterol, sodium, processed meats, refined carbohydrates, sweetened beverages, and trans fat

|

|

Taiwanese dietary pattern23

|

Taiwan

|

Reduce fried foods, sweets and sweetened drinks, high fat pastries, fatty and organ meats

Consume plant-based foods including whole grains, vegetables, fresh fruits, nuts and seeds, tea, and unsaturated fatty acid-rich non-tropical plant oils (e.g., soybean oil, sunflower oil, olive oil); sources of omega-3 fatty acids (e.g., fish, nuts, legumes); good protein foods (low degree processed soy products, fish, egg, and lean animal protein); low in transfats, fried foods, fatty meat, processed meats or fish products

|

|

Dietary pattern based on Dietary Guidelines for Australian Adults11

|

Australia

|

Consume a varied diet rich in vegetables, fruits, wholegrain cereals, lean meat, poultry, fish, eggs, nuts and seeds, legumes and beans, and low fat dairy product

Reduce foods containing saturated and trans fats

Reduce salt to < 6 g/day (≈ 2300 mg sodium)

|

|

High-carbohydrate low-fat dietary pattern10

|

Korea

|

Consume whole grains instead of refined rice

Consume balanced diet including adequate amounts of fish, beans, and fresh vegetables

Consume fresh fruits and milk

Reduce fruit concentrates and sweetened milk

|

|

International atherosclerosis society dietary pattern14,16,24

|

Middle East, USA, Europe

|

Reduce intake of saturated fatty acids to 7% of total calories

Consume a relatively high intake of fruits, vegetables, and fiber

Consume monounsaturated/ polyunsaturated fatty acids

Consume some fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids

Consume foods low in sodium and high in potassium

Reduce processed meats and sugar-sweetened beverages, sweets, grainbased desserts, and bakery foods

Consume plant sterols/stanols (2 g/day) as a dietary adjunct along with soluble/viscous fiber (10–25 g/day)

|

|

|

Indo-Mediterranean Diet15

|

India

|

Consume fruits, vegetables, whole grains like unpolished rice, whole wheat and millets; fatty fish for nonvegetarians and fenugreek seeds, mustard seeds, flax seeds, soya bean oil, mustard oil for vegetarians (as sources of omega-3 fatty acids), nuts

Consume extra-virgin olive oil for cooking, baking, dressing, dips, cold dishes

|

|

|

Intermittent fasting20

|

India

|

Alternate periods of normal food intake with periods of little to no caloric intake

A popular weekly regimen: five days of normal eating with two days of restricted eating (about 400 calories per day)

|

|

For the assessment of the risk of bias, each guideline was rated according to the MiniChecklist tool. Of the 23 guidelines, 18 had a score of seven, three had a score of six, and only one had a score of five. Supplementary Table 1 describes the definitions of MiChe ratings and the scoring for each guideline is available in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2: Evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines for saturated fat intake by Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2023.27

|

Amount of Saturated Fat Intake

|

Reduced saturated fat intake was associated with decreased total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease events

|

|

Replacement of Saturated Fat Intake

|

Replacement of dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat promotes healthy eating patterns and reduces total cholesterol and coronary heart disease events

|

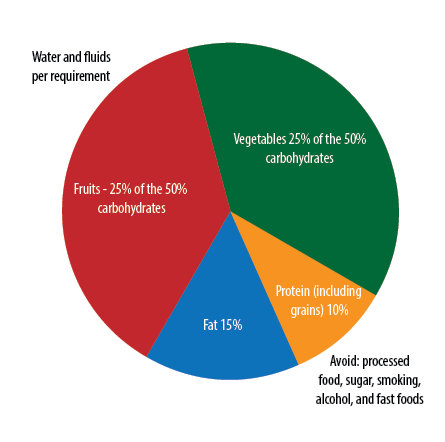

We developed a modified version of the MyPlate meant for the Pakistani public by making modifications including re-labeling the categories of food groups (proteins, vegetables, fruits, fats, water, and substances to avoid with the starches included in fruits and vegetables) and incorporating recommended percentage intake of each macro and micronutrient as shown in Figure 3. The keywords used to search the literature for RCTs reporting a beneficial effect of certain nutrients in comorbidity with dyslipidemia are provided in Supplementary Table 3. The indigenous alternatives were suggested by local expert clinical nutritionists.

Figure 3: Modified dyslipidemia MyPlate for Pakistani population.

Figure 3: Modified dyslipidemia MyPlate for Pakistani population.

Table 3: General dietary recommendations adapted for Pakistani patients with dyslipidemia and associated comorbidities.

|

All the dyslipidemia-related conditions

(Common recommendations)

|

-Remove salt shakers from table.

-Avoid raw salt in salad, egg, or at the table on the cooked food

|

-Avoid trans-fats and saturated fats (vanaspati ghee, bakery shortening, hard margarine, fat spreads, butter, ghee, suet, coconut oil, palm oil)

|

-High-fiber fruits (apple, guava, banana, strawberry, watermelon, melon, plum, papaya, peach)

|

-High fiber vegetables (non starchy vegetables like bell peppers, cucumbers, radishes, carrots, lettuce)

|

-Avoid processed meat and red meat

|

|

Dyslipidemia (without comorbidities)

|

-Increase water intake

|

-MUFAs and PUFAs (seeds, olive oil, canola oil)

-Low-fat dairy products (cottage cheese, skim milk, yogurt)

-Extra virgin olive oil if affordable

|

-

|

-Sterol rich vegetables (peas, beans, tomato, whole wheat)

|

-More plant-based proteins such as pulses (lentils& beans) and nuts in diet

-Fish

-Whole grains

|

|

Dyslipidemia and diabetes miletus

|

-Increase water intake

|

-Omega-3 rich-fatty acids (fish like sardine, mackerel, and rohu, vegetable oil, rapeseed oil, seeds like flaxseeds and chia seeds, walnuts)

-Vitamin B- and B6-rich foods (cottage cheese, yogurt, skim milk)

|

-Low glycemic index fruits (apple, pears, citrus fruits, guava)

-Vitamin C-rich fruits (citrus fruits like oranges and lemons)

|

-Vitamin B-rich vegetables (leafy green vegetables like cabbage, spinach)

-Vitamin B6-rich vegetables (vegetables like potatoes, peas, and corn)

-Vitamin C-rich vegetables (cruciferous vegetables like cabbage, turnip)

|

-Low glycemic index nuts (peanuts, almonds, walnuts)

-Vitamin D rich foods (liver, fatty fish like pomfret, sardine)

-Vitamin E-rich foods (peanuts, sunflower seeds, almonds)

|

|

Dyslipidemia and hypertension

|

-Increase water intake

|

-MUFAs and PUFAs (seeds, olive oil, canola oil)

-Low-fat dairy products (cottage cheese, skim milk, yogurt)

-Extra virgin olive oil if affordable

|

-Flavanol-rich sources of food like cocoa powder/chocolate.

|

-Polysulfide-rich foods like garlic or aged garlic extracts

|

-Coenzyme Q-rich foods (red meat, liver, fish like sardines and tuna)

|

|

Dyslipidemia and chronic kidney disease

|

-Increase water intake

|

-Omega-3 fatty acids-rich foods (sunflower oil, sesame oil)

|

-Avoid potassium-rich fruits (bananas, apricots)

|

-Avoid potassium-rich vegetables (potatoes, tomatoes, spinach)

|

-Omega-3 fatty acids-rich foods (walnuts, sunflower seeds, sardines)

|

|

Dyslipidemia and steatotic liver disease (MASLD/NAFLD)

|

-Increase water intake

|

-Omega-3 fatty acids (like flax seed oils)

|

-Antioxidant-rich fruits (citrus fruits like lemon and oranges, plum, pomegranate)

|

-Antioxidant-rich vegetables (spinach, beetroot, carrots)

|

-Omega-3 fatty acids (fish like sardines, salmon, chia seeds, flax seeds)

|

|

Dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome

|

-Increase water intake

-Calcium rich drinks (milk, yogurt)

|

-Fermented dairy products (yogurt, cheese)

|

-Polyphenols-rich foods (strawberry, grapes, cherries)

-Lycopene rich-foods (apricot, papaya, melon)

-Carotenoids-rich foods (watermelon, mango, oranges)

-Flavonoids rich-foods (berries, cherries)

-Folate rich-foods (banana, strawberry, mango)

-Vitamin C rich-foods (citrus fruits like lemon and oranges)

-Resveratrol-rich foods (grapes, plums, apple)

|

-Calcium and vitamin B rich foods (leafy green vegetables like cabbage and spinach)

-Vitamin C-rich foods (cruciferous vegetables like cauliflower and spinach)

-Organosulfur compounds rich-foods (cauliflower, garlic, onion)

|

-Magnesium-rich foods (almonds, cashews)

-Selenium and zinc rich foods (eggs, sunflower seeds, sardines, whole grains)

-Vitamin B rich foods (beef liver)

-Vitamin D rich foods (beef liver and fatty fish)

-Vitamin E rich foods (almonds, peanuts, sunflower seeds)

|

|

Dyslipidemia and pancreatitis

|

-Increase water intake

-Calcium rich foods (milk, yogurt)

|

-Fats-rich in MUFAs and PUFAs (seeds, olive oil, canola oil)

-Low-fat dairy products (cottage cheese, skim milk, yogurt)

-Extra virgin olive oil if affordable

|

-Fiber-rich fruits (watermelon, melon, plums, papaya, peaches)

|

-Calcium rich foods (vegetables like lettuce, and zucchini)

-Vitamin K rich foods (vegetables like lettuce, zucchini, carrots)

|

-Magnesium-rich foods (almonds, cashews)

-Vitamin A-rich foods (liver, fish such as salmon)

-Vitamins B1-, B2-, B3-, and B12-rich foods (cereal grains, red meat, and fish)

-Vitamin D-rich foods (beef liver and fatty fish)

-Vitamin E-rich foods (almonds, peanuts, sunflower seeds)

|

|

Dyslipidemia and thyroid disease

|

-Increase water intake

|

-MUFAs and PUFAs (seeds, olive oil, canola oil)

-Low-fat dairy products (cottage cheese, skim milk, yogurt)

-Extra virgin olive oil if affordable

|

-Iron-rich foods (prunes, apricot, raisins)

-Potassium-rich foods (apricots, banana, pomegranate)

-Vitamin C-rich foods (citrus fruits like lemon and oranges)

-Phenol-rich fruits (apple, mango, pomegranate)

-Resveratrol-rich foods (grapes, berries, apple)

|

-Vitamin B rich foods (vegetables like cabbage and spinach, cauliflower)

|

-Iodine (beef liver, eggs, and fish like salmon)

-Selenium and zinc-rich foods (eggs, sunflower seeds, sardines, whole grains)

-Copper-rich foods (organ meats, whole grain)

-Magnesium-rich foods (almonds, cashews)

-Vitamin A-rich foods (liver, fish)

-Vitamin B-rich foods (beef liver)

-Vitamin D-rich foods (beef liver and fatty fish)

-Prebiotics (almonds, chickpeas) and probiotics (yogurt)

-Inositol-rich foods (whole grains and legumes)

-Carnitine-rich foods (legumes, eggs, seafood, lean meats)

-Melatonin rich foods (eggs, fish such as salmon and sardines)

|

NMUFA: monounsaturated fat; PUFA: polyunsaturated fat; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (old term for MASLD).

This Modified MyPlate differs from the Healthy Eating Plate created by the Harvard Health Publishing in two aspects; a section describing the substances to avoid and the lack of a grain section. According to Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition,26 cereals and grains including wheat and rice, etc. are staple foods of Pakistan, consumed as protein sources. The suggested percentages were based on the guidelines defined by the Lipid Association of India.20

It has been recommended that < 10% of the total dietary fat should be acquired from saturated fats.26 It is advisable for the dietitians of Pakistan to employ Saturated Fat 2023 Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guidelines depicted in Table 2.27

After analysis of the guidelines and an extensive review of the literature, we developed a generally applicable dietary recommendations for dyslipidemia and its associated comorbidities. Based on this composite nutritional composition, foods with equivalent nutritional values available in Pakistan were identified and included in Table 3.

Discussion

The analysis of the guidelines for dyslipidemia management from various regions covered by this systematic review sheds light on two prominent features. Firstly, stratification of ASCVD risk remains important for guiding interventions, despite some limitations in the risk calculation method. Secondly, the management of any type of dyslipidemia relies heavily on non-pharmacological interventions which include healthy dietary patterns, physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoidance of detrimental habits such as smoking, stress, etc. Almost all the guidelines acknowledge the benefits of adopting dietary approaches to stop hypertension, Mediterranean-style diet, as well as a plant-based diet, while emphasizing the need for regional food adaptations.15,16,18–20

A comparison of major dyslipidemia guidelines—including the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines, Multisociety Blood Cholesterol Management Guideline, the 2021 European Society of Cardiology Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Guidelines, and the 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society’s Management of Dyslipidemia guidelines—revealed a consistent approach.28 While our study encompassed a larger number of guidelines, little variation was observed in the aspects analyzed compared to other studies.28 Risk stratification relies on population-specific calculators, with the levels of LDL-C as the primary indicator, supplemented with the levels of other lipids such as non-HDL-C, ApoB, and Lp(a) in selected patient groups. Lifestyle modifications, particularly dietary changes are recommended across most guidelines, aligning with previous studies.28,29

According to the 2019 Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition, food availability in the country as measured by kg/capita/year has been steady. This is indicated by the nationwide accessibility of major food sources like wheat, rice, maize, fats and oils, meat, milk, vegetables, fruits, and pulses for the growing population of Pakistan.26 Despite sufficient supply, about 35% of Pakistani population are poor and unable to acquire adequate nutrients.26 This is likely to cause macro and micronutrient deficiencies among the economically weaker section of the populace, negatively impacting their overall health and productivity.

Pakistani cuisine is renowned for its rich flavors and diverse culinary traditions. A nutritious combination of wheat flatbreads (chapati) and lentils (dal), with small quantities of curd, ghee, vegetables, or meat has been a traditional staple diet among ordinary Pakistanis. More affluent households may indulge in richer traditional foods such as biryani and pulao — basmati rice cooked with meat, spices, and aromatic herbs. Nihari is a flavorful slow-cooked stew made from tender meat and bone marrow, infused with spices. Traditional snacks include deep-fried sweet jalebis, pakoras, and samosas. A popular breakfast combination is halwa-puri, a semolina-based sweet (halwa) eaten with deep-fried wheat bread (puri). Milky sweet tea (chai) is a national passion of Pakistanis. Regarding fruits, a wide variety is grown locally, including banana, guava, apple, apricot, orange, mango, etc.

There are great variations in regional dietary practices across Pakistan, whose territory extends from the Himalayas to the Arabian Sea. The sajji method of roasting whole lamb in a deep pit is unique to Balochi cuisine. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa residents are heavy meat eaters and tea drinkers, mainly green tea. The Punjabi cuisine includes large amounts of ghee (clarified butter), rice, and spices (masala). The Punjabi people are also known for their variety of wheat breads (rotis) and sophistication in cuisine, a tradition that hearkens to the Mughal era. Muhajirs in the Southern province of Sindh have added their own contribution to Pakistan’s gastronomic diversity by carefully preserving and popularizing the traditional food habits and cooking styles of the regions in India they migrated from.

In the last few decades, urbanization, globalization, and acculturation have resulted in the entry of international fast-food chains and their local imitators, which serve palatable but fatty and sugary foods and beverages. The consumption of sweets, bakery products, and fried foods have increased significantly, especially among the youth. Coupled with lower activity levels, ‘lifestyle’ diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and CVD, are affecting Pakistanis of younger ages.

According to the 2019 Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition, the consumption patterns of the Pakistani population are very high in detrimental fats, sugars, and salt, with low intake of fruits and vegetables.24 Moreover, the portion sizes do not correspond with the caloric requirement, leading to obesity. To combat the accelerating cases of dyslipidemia and other lifestyle-linked conditions in Pakistan, healthcare providers specifically local dietitians must focus on modifying the dietary regime of each patient according to the above guidelines. Some beneficial strategies include the development and distribution of pamphlets containing dietary recommendations for dyslipidemia as well as for each specific coexistent condition. They should be available in the local language of the patient and should also highlight local food sources to increase compliance. To increase conformity with the guidelines, it is also imperative to increase the diffusion of nutritionists amongst the populace so that the obstacles of the language barrier and regional sources of food can be overcome.

Body mass index (BMI) is an indicator of the nutritional status assessed by taking the weight of adults in kilograms divided by height in meters square. According to the WHO, the categories for the Asian population have been defined as:

- 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 (increasing but acceptable risk)

- 23–27.4 kg/m2 (increased risk)

- 27.5 kg/m2 or higher (high risk of developing chronic health conditions)

To maintain an ideal BMI, the amount of nutrients recommended for dyslipidemia and other conditions must be according to the 2019 Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition.26

Cereals are the main staple in Pakistani food, providing 62% of the total energy in the diet.30 The consumption of fruits and vegetables, fish, and meat is low either due to widespread poverty or seasonal fluctuations in availability, leading to micronutrient deficiencies such as zinc, iodine, and iron, in this population. Most physicians in Pakistan recommend lifestyle modification along with statins and ezetimibe as a preferred treatment regimen.31 However, tailored dietary plans are challenging particularly in a low-income country context. Educating the population of Pakistan of cost-effective nutritional alternatives along with the importance of physical activity is vital to combat dyslipidemia for which the role of dietitians is undeniable.

Due to cultural and economic differences between the communities of Pakistan and foreign countries, it is essential to use international guidelines as a base for developing suitable dietary recommendations. To promote the effective implementation of beneficial dietary practices conforming to Pakistani culture, the following tips can be used for practical application of dyslipidemia guidelines in Pakistan.30 However, they are meant to be tailored based on individual preferences and health goals.

- Limit portions for foods that are higher in fat, sugar, or salt, like samosas, pakoras, and other fried appetizers; curries made with a lot of oil, ghee, or coconut milk; and desserts.

- Fill half of a 10-inch plate (the size of a regular dinner or paper plate) with colorful, non-starchy vegetables such as spinach, eggplant, okra, carrots, green beans, bitter melon, tomatoes, and green salad.

- Prepare or choose mostly salad or vegetable dishes made with a little oil. Use vinegar and lemon for salad dressing.

- Limit deep-fried vegetables and those made with cream or a lot of oil.

- Prefer yogurt raita, mint, or coriander chutney, and kachumber (chopped salad), instead of salty preserved pickle or chutney, or only take a small amount.

- Fill only a quarter of your plate with cereals and starchy vegetables (rice, bread, potatoes, green peas, etc.).

- Prefer high-fiber cereals like brown rice, cracked wheat, and wholegrain breads like chapati or roti.

- Eat plain steamed or boiled rice or grains and baked breads without ghee or butter.

- Avoid or minimize consumption of fried potatoes, rice, deep-fried or oily breads (such as puris or parathas), and snacks (like samosas, pakoras, or chaats).

- Eat 56–85 g of protein-rich food (lean meat, fish, dal, or paneer), or enough to fill a quarter of the plate.

- Prefer dishes with baked or grilled lean meat or poultry (chicken without the skin, beef or mutton after removing fat), fish, or shrimp.

- Prepare/eat beans, lentils, or dal dishes made with minimum oil or ghee.

- Avoid high-fat foods like meat or vegetable curries cooked with coconut milk, cream, ghee, or much oil.

- Choose fresh fruits such as oranges, apples, or strawberries for dessert.

- Avoid (or severely limit) desserts high in sugar and fat, like cookies, cakes, kulfi, halwa, kheer, rasmalai, gulab jamun, raasgula, barfi, other desserts in sugar syrup, and those made with cream or ghee.

Dyslipidemia

The recommendations presented in supplementary Figure 1 are supported by most of the guidelines. Restriction of salt, trans fat, and saturated fats prevents the development of atherosclerotic plaques in vessels while the opposite role is played by monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids.14,16,19,20 Phytosterols and fibers help reduce the amount of cholesterol absorbed from diet, thereby decreasing its absorption in the blood. Hence, fiber-rich fruits and vegetables are an essential part of a hypolipidemic diet [Table 3].14,15,16,20,22

Dyslipidemia and DM

An elevated risk of malnutrition is present in individuals suffering simultaneously from two chronic conditions, especially if dietary pattern is involved in the pathophysiology. Supplementation with vitamins B, B6, C, and D is beneficial.32–34 Similarly, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are beneficial due to their anti-inflammatory properties and can be effective in combating pro-inflammatory conditions, particularly dyslipidemia despite having no benefit in DM.35 While many guidelines for dyslipidemia support the increased intake of nuts and fruits, patients with both dyslipidemia and diabetes should focus on low-glycemic index nuts and fruits, particularly apples and guavas due to their high-fiber content [Table 3].36

Dyslipidemia and Hypertension

Green tea, rich in polyphenols, has antioxidant features that provide protection against cardiovascular events.37 A RCT by Heiss et al,38 observed that the intake of cocoa due to its high content of flavanols improved the systolic blood pressure and endothelial function, thereby highlighting its beneficial role in dyslipidemia and hypertension. Garlic has long been reported to have hypolipidemic and hypotensive effects at the level of vascular endothelium [Table 3].39

Dyslipidemia and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

A diet rich in fiber and low in protein is recommended for individuals with both dyslipidemia and CKD. These dietary patterns not only decrease LDL-C, but they also improve anemia and delay the decline in glomerular filtration rate. A lower intake of potassium and phosphorus is beneficial in CKD.16,40 However, fruits and vegetables, which are recommended for both conditions, are rich in these minerals. Hence, each patient should be provided with an individualized diet plan bearing in mind these restrictions [Table 3].

Dyslipidemia and Steatotic Liver Disease

Steatotic liver disease (MASLD/NAFLD) is a pro-inflammatory condition, so incorporating various antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids and fiber in the diet can have a dual benefit of ameliorating dyslipidemia and steotatic liver disease.41 Similarly, a low glycemic index diet has been observed to reduce the hepatic fat stores [Table 3].42

Dyslipidemia and Pancreatitis

In patients with dyslipidemia and acute/chronic pancreatitis, there is a high risk of deficiency of vitamins and minerals, hence supplementation with vitamins A, D, E, K and minerals like calcium and magnesium is important.43 A dietary regime low in fiber should be adopted in chronic pancreatitis as it aggravates steatorrhea.43 In inherited hyperlipidemic conditions like familial chylomicronemia syndrome, daily fat intake is restricted to 20 g.44 Therefore, optimal fat intake is important depending on the type of pancreatitis. For mild acute pancreatitis, a low-fat diet is generally preferred.43 In chronic pancreatitis, a well-balanced diet is recommended with up to 30–33% of the total energy coming from fats [Table 3].43

Dyslipidemia and Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome consists of multiple pathologies existing together with low-grade inflammation. An adequate intake of various antioxidants including vitamin E, polyphenols, lycopenes, carotenoids, and resveratrol is recommended.45,46 Similarly, organosulfur compound-rich substances like garlic are recommended due to their profound hypotensive and hypolipidemic effects which can be used to control the dyslipidemia and hypertension seen in metabolic syndrome [Table 3].39

Dyslipidemia and Hyperthyroidism

Certain nutrients like carnitine and inositol are beneficial in thyroid disease due to their effects on the functioning of thyroid hormones.47 The intake of dietary iodine should be regulated in hyperthyroidism, especially in individuals on anti-thyroid drugs [Table 3].48

Dyslipidemia and Heart Failure

Heart failure is a chronic condition with progressively increasing inflammatory burden as the disease worsens. Salt restriction is recommended as it is beneficial to combat both dyslipidemia and heart failure.19 Nutrients like coenzyme Q1 and thiamine are also recommended due to their antioxidant activity and improvement of cardiac functions.49,50 Due to dietary restrictions in both conditions, there is a high risk of developing malnutrition which can be overcome by amino acid supplementation in a high-protein diet are mainly from plant sources [Table 3].25

Precision nutrition is an advanced approach to the treatment of various acute and chronic conditions by involving dietary plans. It is based on the knowledge of an individual’s genetic build, microbiome, and metabolic response to specific foods. The main obstacles to the introduction and application of precision nutrition in Pakistan are funding and facilities.

Nutritional demands of sexes and age groups differ, owing to their diverse physical activity levels and metabolic rates. While this study outlines the various food sources that are beneficial in specific conditions coexistent with dyslipidemia, it is to be noted that the amount of these nutrients should be tailored while bearing sex and age factors in mind. Moreover, the study provides an overview of recommended local dietary supplementation derived from international guidelines and could be used as a basis for developing guidelines for Pakistan.

Conclusion

Pakistan is a developing country with problems of overpopulation, low literacy, and economic constraints. Our daily lifestyles and dietary patterns are still suboptimal. All these factors combined play a major causative role in the rising prevalence of dyslipidemia in Pakistan. To combat this problem, approaches should be developed that cater to our issues of poverty while simultaneously reducing the burden of high cholesterol in our population. Hence, it is important to develop dietary regimes according to our economy and resources.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. 2020 [2023 September 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death.

- 2. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al; GBD-NHLBI-JACC Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases Writing Group. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020 Dec;76(25):2982-3021.

- 3. Liu T, Zhao D, Qi Y. Global trends in the epidemiology and management of dyslipidemia. J Clin Med 2022 Oct;11(21):6377.

- 4. World Health Organization. Number of deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases, by type of disease and sex. 2019 [2024 April 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/number-of-deaths-attributed-to-non-communicable-diseases-by-type-of-disease-and-sex.

- 5. Chua A, Adams D, Dey D, Blankstein R, Fairbairn T, Leipsic J, et al. Coronary artery disease in East and South Asians: differences observed on cardiac CT. Heart 2022 Feb 1;108(4):251-257.

- 6. Alshamiri M, Ghanaim MMA, Barter P, Chang KC, Li JJ, Matawaran BJ, et al. Expert opinion on the applicability of dyslipidemia guidelines in Asia and the Middle East. Int J Gen Med 2018;11:313-322.

- 7. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines; Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington: National Academies Press; 2011.

- 8. Siebenhofer A, Semlitsch T, Herborn T, Siering U, Kopp I, Hartig J. Validation and reliability of a guideline appraisal mini-checklist for daily practice use. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016 Apr;16(1):39.

- 9. Harvard Health Publishing. Harvard Medical School. Comparison of the healthy eating plate and the USDA’s MyPlate. 2017 [2023 September 3]. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/comparison-of-healthy-eating-plate-and-usda-myplate.

- 10. Rhee EJ, Kim HC, Kim JH, Lee EY, Kim BJ, Kim EM, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia. Korean J Intern Med (Korean Assoc Intern Med) 2019 Jul;34(4):723-771.

- 11. National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance. Guidelines for the management of absolute cardiovascular disease risk. National Heart Foundation of Australia. 2012 [cited 2023 September 3]. Available from: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/getmedia/4342a70f-4487-496e-bbb0-dae33a47fcb2/Absolute-CVD-Risk-Full-Guidelines_2.pdf.

- 12. Klug E, Raal FJ, Marais AD, et al; South African Heart Association. (S A Heart); Lipid and Atherosclerosis Society of Southern Africa (LASSA). South African dyslipidaemia guideline consensus statement. S Afr Med J 2012 Feb;102(3 Pt 2):178-187.

- 13. Précoma DB, Oliveira GM, Simão AF, Dutra OP, Coelho OR, Izar MC, et al. Updated cardiovascular prevention guideline of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology - 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol 2019 Nov;113(4):787-891.

- 14. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019 Jun;73(24):e285-e350.

- 15. Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, et al. 2021 Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can J Cardiol 2021 Aug;37(8):1129-1150.

- 16. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020 Jan;41(1):111-188.

- 17. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002 Dec;106(25):3143-3421.

- 18. O’Malley PG, Arnold MJ, Kelley C, Spacek L, Buelt A, Natarajan S, et al. Management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular disease risk reduction: synopsis of the 2020 updated U.S. department of veterans affairs and U.S. department of defense clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2020 Nov;173(10):822-829.

- 19. Handelsman Y, Jellinger PS, Guerin CK, Bloomgarden ZT, Brinton EA, Budoff MJ, et al. Consensus statement by the American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology on the management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease algorithm - 2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2020 Oct;26(10):1196-1224.

- 20. Puri R, Mehta V, Iyengar SS, Narasingan SN, Duell PB, Sattur GB, et al. Lipid association of India expert consensus statement on management of dyslipidemia in Indians 2020: part III. J Assoc Physicians India 2020 Nov;68(11[Special]):8-9.

- 21. Chen H, Chen WW, Chen WX, et al. Joint committee for guideline revision. 2016 Chinese guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. J Geriatr Cardiol 2018 Jan;15(1):1-29.

- 22. Kinoshita M, Yokote K, Arai H, Iida M, Ishigaki Y, Ishibashi S, et al; Committee for Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Atherosclerosis. Japan atherosclerosis society (JAS) guidelines for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018 Sep;25(9):846-984.

- 23. Huang PH, Lu YW, Tsai YL, Wu YW, Li HY, Chang HY, et al. Expert committee for the Taiwan lipid guidelines for primary prevention. 2022 Taiwan lipid guidelines for primary prevention. J Formos Med Assoc 2022 Dec;121(12):2393-2407.

- 24. Alsayed N, Almahmeed W, Alnouri F, Al-Waili K, Sabbour H, Sulaiman K, et al. Consensus clinical recommendations for the management of plasma lipid disorders in the Middle East: 2021 update. Atherosclerosis 2022 Feb;343:28-50.

- 25. Banach M, Burchardt P, Chlebus K, Dobrowolski P, Dudek D, Dyrbuś K, et al. PoLA/CFPiP/PCS/PSLD/PSD/PSH guidelines on diagnosis and therapy of lipid disorders in Poland 2021. Arch Med Sci 2021 Nov;17(6):1447-1547.

- 26. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform, Government of Pakistan. Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition. [cited 2023 September 3]. Available from: https://www.pc.gov.pk/uploads/report/Pakistan_Dietary_Nutrition_2019.pdf.

- 27. Johnson SA, Kirkpatrick CF, Miller NH, Carson JA, Handu D, Moloney L. Saturated fat intake and the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in adults: an academy of nutrition and dietetics evidence-based nutrition practice guideline. J Acad Nutr Diet 2023 Dec;123(12):1808-1830.

- 28. Singh M, McEvoy JW, Khan SU, Wood DA, Graham IM, Blumenthal RS, et al. Comparison of transatlantic approaches to lipid management: The AHA/ACC/multisociety guidelines vs the ESC/EAS guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc 2020 May;95(5):998-1014.

- 29. Aygun S, Tokgozoglu L. Comparison of current international guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia. J Clin Med 2022 Dec;11(23):7249.

- 30. Khan R. Pakistan culture. In: Cultural competency for the nutrition professionals. Chicago:ll: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2016. p. 325-342.

- 31. Sadiq F, Shafi S, Sikonja J, Khan M, Ain Q, Khan MI, et al. PAKISTAN familial hypercholesterolemia collaborators. Mapping of familial hypercholesterolemia and dyslipidemias basic management infrastructure in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 2023 Feb;12(0):100163.

- 32. Didangelos T, Karlafti E, Kotzakioulafi E, Margariti E, Giannoulaki P, Batanis G, et al. Vitamin B12 supplementation in diabetic neuropathy: a 1-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2021 Jan;13(2):395.

- 33. Boonthongkaew C, Tong-Un T, Kanpetta Y, Chaungchot N, Leelayuwat C, Leelayuwat N. Vitamin C supplementation improves blood pressure and oxidative stress after acute exercise in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Chin J Physiol 2021;64(1):16-23.

- 34. Cojic M, Kocic R, Klisic A, Kocic G. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic and oxidative stress markers in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 6-month follow up randomized controlled study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021 Aug;12:610893.

- 35. Wang F, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Liu X, Xia H, Yang X, et al. Treatment for 6 months with fish oil-derived n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids has neutral effects on glycemic control but improves dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetic patients with abdominal obesity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2017 Oct;56(7):2415-2422.

- 36. Bergia RE, Giacco R, Hjorth T, Biskup I, Zhu W, Costabile G, et al. Differential glycemic effects of low- versus high-glycemic index Mediterranean-style eating patterns in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: The MEDGI-carb randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2022 Feb;14(3):706.

- 37. Al-Shafei AI, El-Gendy OA. Regular consumption of green tea improves pulse pressure and induces regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients. Physiol Rep 2019 Mar;7(6):e14030.

- 38. Heiss C, Sansone R, Karimi H, Krabbe M, Schuler D, Rodriguez-Mateos A, et al; FLAVIOLA Consortium. European union 7th framework program. Impact of cocoa flavanol intake on age-dependent vascular stiffness in healthy men: a randomized, controlled, double-masked trial. Age (Dordr) 2015 Jun;37(3):9794.

- 39. Ried K, Travica N, Sali A. The effect of kyolic aged garlic extract on gut microbiota, inflammation, and cardiovascular markers in hypertensives: the GarGIC trial. Front Nutr 2018 Dec;5:122.

- 40. Li Y, Han M, Song J, Liu S, Wang Y, Su X, et al. The prebiotic effects of soluble dietary fiber mixture on renal anemia and the gut microbiota in end-stage renal disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Transl Med 2022 Dec;20(1):599.

- 41. Šmíd V, Dvořák K, Šedivý P, Kosek V, Leníček M, Dezortová M, et al. Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on lipid metabolism in patients with metabolic syndrome and NAFLD. Hepatol Commun 2022 Jun;6(6):1336-1349.

- 42. Bawden S, Stephenson M, Falcone Y, Lingaya M, Ciampi E, Hunter K, et al. Increased liver fat and glycogen stores after consumption of high versus low glycaemic index food: a randomized crossover study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017 Jan;19(1):70-77.

- 43. Arvanitakis M, Ockenga J, Bezmarevic M, Gianotti L, Krznarić Ž, Lobo DN, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Clin Nutr 2020 Mar;39(3):612-631.

- 44. Williams L, Rhodes KS, Karmally W, Welstead LA, Alexander L, Sutton L. Patients and families living with FCS. Familial chylomicronemia syndrome: bringing to life dietary recommendations throughout the life span. J Clin Lipidol 2018;12(4):908-919.

- 45. Takagi T, Hayashi R, Nakai Y, Okada S, Miyashita R, Yamada M, et al. Dietary intake of carotenoid-rich vegetables reduces visceral adiposity in obese Japanese men-a randomized, double-blind trial. Nutrients 2020 Aug;12(8):2342.

- 46. Tomé-Carneiro J, Gonzálvez M, Larrosa M, García-Almagro FJ, Avilés-Plaza F, Parra S, et al. Consumption of a grape extract supplement containing resveratrol decreases oxidized LDL and ApoB in patients undergoing primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a triple-blind, 6-month follow-up, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Mol Nutr Food Res 2012 May;56(5):810-821.

- 47. Benvenga S, Ruggeri RM, Russo A, Lapa D, Campenni A, Trimarchi F. Usefulness of L-carnitine, a naturally occurring peripheral antagonist of thyroid hormone action, in iatrogenic hyperthyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001 Aug;86(8):3579-3594.

- 48. Huang H, Shi Y, Liang B, Cai H, Cai Q, Lin R. Optimal iodine supplementation during antithyroid drug therapy for Graves’ disease is associated with lower recurrence rates than iodine restriction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018 Mar;88(3):473-478.

- 49. Schoenenberger AW, Schoenenberger-Berzins R, der Maur CA, Suter PM, Vergopoulos A, Erne P. Thiamine supplementation in symptomatic chronic heart failure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot study. Clin Res Cardiol 2012 Mar;101(3):159-164.

- 50. Mortensen SA, Rosenfeldt F, Kumar A, Dolliner P, Filipiak KJ, Pella D, et al. Q-SYMBIO study investigators. The effect of coenzyme Q10 on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from Q-SYMBIO: a randomized double-blind trial. JACC Heart Fail 2014 Dec;2(6):641-649.