Apreviously healthy, six-year-old girl presented with a two-month history of bloody diarrhea, associated with abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, and intermittent fever. She had not traveled recently and reported no contact with sick people or exposure to animals.

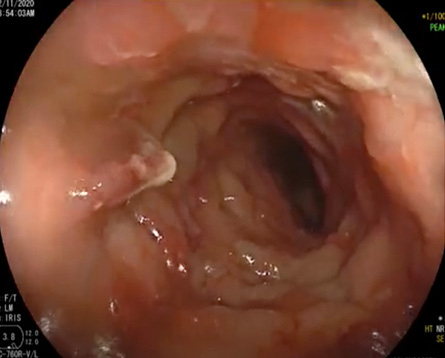

Physical examination revealed a well-looking child with mild conjunctival pallor. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in the left iliac fossa with no palpable mass or organomegaly. A perianal examination was declined. Colonoscopy demonstrated severe ulcerating rectal mucosa with fungated lesions extending into the sigmoid colon [Figure 1]. Histological analysis of rectal biopsy revealed distorted crypt architecture with crypt branching and increased inflammatory cells, mostly eosinophils. The clinical, biochemical, and histological findings were suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Consequently, the patient was initiated on a regimen of 5-aminosalicylic acid and oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day). However, her condition worsened, and she developed a fever with severe perianal pruritus and pain. Therefore, her immunosuppressive therapy was escalated to intravenous methylprednisolone, mercaptopurine (6-MP), and infliximab. She also received intravenous metronidazole and cefuroxime.

Figure 1: Endoscopy image showing severely ulcerating rectal mucosa with fungated lesions extending into the sigmoid colon.

Figure 1: Endoscopy image showing severely ulcerating rectal mucosa with fungated lesions extending into the sigmoid colon.

Laboratory investigations revealed a high C- reactive protein of 66 mg/L and hypochromic microcytic anemia as revealed by a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 8.7 g/dL (ref. range = 11.5–15.5) and a normal total white blood count of 10.5 × 109. The patient also had thrombocytosis (840 × 109/L) (150–450) and eosinophilia (eosinophils 2.8 × 109 /L (0.1–0.8). Her iron level was low at 2 umol/L (6–35) and her ferritin level was high at 266 ug/L (4–67).

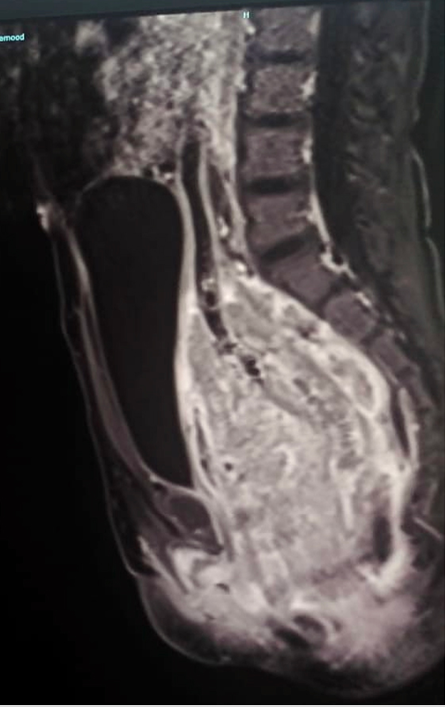

Despite the enhanced immunosuppressive therapy, her symptoms continued to worsen, and she developed urinary retention. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the pelvis revealed severe irregular thickening of the rectal wall extending up to the sigmoid colon. There was evidence of inflammatory mass (rectal wall thickness measured 1.8 cm for a length of 10 cm) which was compressing the surrounding structures [Figure 2].

Figure 2: MRI of the pelvis (sagittal view) at initial presentation showing extensive thickening and inflammation of the whole rectum (10 cm in length) including the rectosigmoid junction. The inflammatory mass is seen compressing the surrounding structure including the uterus, urinary bladder, and subcutaneous fat and facia.

Figure 2: MRI of the pelvis (sagittal view) at initial presentation showing extensive thickening and inflammation of the whole rectum (10 cm in length) including the rectosigmoid junction. The inflammatory mass is seen compressing the surrounding structure including the uterus, urinary bladder, and subcutaneous fat and facia.

Questions

- What is your diagnosis?

- How to rule out other possible differential diagnosis?

- What is the gold standard test to make the diagnosis?

- How would you manage this patient?

Answers

- Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis.

- Work up for primary immunodeficiency, tuberculosis, malignancies, and monogenic IBD molecular testing.

- Tissue culture. Histopathology can also help in making the diagnosis.

- Voriconazole or itraconazole for a minimum of 9–12 months.

Discussion

The possibility of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis, a rare fungal infection, was raised, given our patient’s deterioration on IBD therapy, the presence of peripheral eosinophilia, abdominal mass, and increased eosinophilic infiltration in colonic biopsy. A deep biopsy to confirm the diagnosis was deferred due to the potential for significant complications as identified by the surgical team.

After the patient developed urinary retention, her immunosuppressive medications were stopped, and she was commenced on empirical itraconazole 5 mg/kg twice daily. Within days, her condition significantly improved, both clinically and biochemically. Her inflammatory markers and eosinophil count normalized within two weeks. A follow-up pelvis MRI taken six weeks after initiating itraconazole therapy showed significant normalization of the rectal wall thickness with reduced perirectal edema and inflammation. Subsequent clinical follow-ups showed significant improvement in her symptoms.

Conditions that can mimic IBD can be broadly classified based on their etiologies into infectious and noninfectious. Among the former is basidiobolomycosis,1 a rare fungal infection caused by Basidiobolus ranarum, an environmental saprophyte. This fungus is found in soil, dung of amphibians, reptiles, and decaying vegetables in tropical and subtropical regions.2 It can cause skin, soft tissue, and gastrointestinal infections in immunocompetent patients.3 Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is an emerging fungal infection that can affect immunocompetent patients including children.2,3 Only about 120 cases of GIB have been reported worldwide, mostly in men and children.3 Previous reports suggest that infection can be acquired after a minor trauma to the skin or via ingestion of food contaminated with the fungus from soil or

animal dung.2,4

Reported cases are rising due to better awareness among clinicians.3 Recently in Oman, Al Masqari et al,3 reported a case series of five patients with GIB, who were mostly children from A'Dakhiliyah governorate, managed at the Royal Hospital. Another study in 2022 by Al-Hatmi et al,5 reported a novel pathogenic species Basidiobolus omanensis in four Omani patients.

Due to the rarity of the disease and unspecific presenting signs and symptoms, the diagnosis of this condition has been challenging. Clinical presentation of GIB includes abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, diarrhea, or even constipation, abdominal distention, or abdominal mass which can mimic IBD.4 Delaying GIB treatment might cause disseminated disease and poor outcome.3

The gold standard to diagnose GIB is tissue culture, but histopathology can also help, by identifying typical features such as chronic granulomas with high eosinophils infiltrate and the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon.3 Despite the challenges in reaching the diagnosis, the best diagnostic clue of this rare infection is considering GIB possibility in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with abdominal pain and fever, associated with intestinal or colonic mass and/or wall thickening, and concomitant high ESR and eosinophilia.3,4 The lack of awareness of this infection as an IBD mimicker initially led to misdiagnosis and the consequent deterioration in our patient’s condition. Prompt antifungal therapy with or without surgery is recommended to eradicate the infection and prevent recurrence.3,4

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Consent for publication has been received from the patient’s family.

references

- 1. Gecse KB, Vermeire S. Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: imitations and complications. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018 Sep;3(9):644-653.

- 2. Al Jarie A, Al-Mohsen I, Al Jumaah S, Al Hazmi M, Al Zamil F, Al Zahrani M, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003 Nov;22(11):1007-1014.

- 3. Al Masqari M, Al Maani A, Ramadhan F. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: an emerging fungal infection of the gastrointestinal tract, the Royal Hospital (Sultanate of Oman) experience. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2021;3:46-49.

- 4. Albishri A, Shoukeer M, Shreef K, Hader H, Ashour M H, ALshirbiny H, et al. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2020;55:101411.

- 5. Al-Hatmi A, Al Yazidi L, Al-Housni S, Al-Kharousi A, Al Sulaimi I, Al-Jahdhami H, et al. P487 Basidiobolus omanensis, an emerging pathogen to watch out for?. Medical Mycology 2022 Sep;60(Suppl_1):myac072P487.