Approximately one in 25 000–100 000 pregnancies worldwide is complicated by thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), a rare life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy that mimics the hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) sharing their underlying pathologies such as hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and multi-vascular thrombus formation.1 Associated with high maternal and perinatal mortality, TTP can cause acute renal insufficiency, ischemic heart disease, altered mental status, and end-organ damage in the mother, leading to miscarriage and intrauterine fetal death.2,3

Plasmapheresis (PTX), the current cornerstone for treating of TTP, has reduced mortality associated with TTP in pregnancy from 58.1% in 1980 to 9% in 1996.4 Management of TTP in pregnancy is by plasma therapy with continuation of pregnancy, but in cases of superimposed severe preeclampsia, it mandates delivery. TTP with superimposed preeclampsia in pregnancy has higher maternal mortality rates (44.4%) compared to TTP alone (21.8%).5 These challenge the managing team to make the right decision in cases where undiagnosed TTP with superimposed preeclampsia presents for the first time in preterm pregnancy.

High index of suspicion for TTP, early PTX, and prompt obstetric decision regarding delivery can save both mother and fetus. This case also showed the capability of multidisciplinary teams for efficient and decisive diagnosis and management in challenging conditions such as thrombocytopenia associated with pregnancy.

Case Report

A 32-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 2, para 1, with no living child), with severe thrombocytopenia at 26 weeks of gestation, was referred to the hematology and obstetrics care at our tertiary hospital. Nine years ago, she had a complicated pregnancy with features of TTP (undiagnosed), culminating in the delivery of a stillborn fetus at 24 weeks gestation. Thereafter, she avoided pregnancy by adopting natural methods of contraception.

In her present unplanned pregnancy, all her antenatal checkups were normal till 24 weeks and five days when her blood pressure increased. Her body mass index was 25.6 kg/m2. She was started on antihypertensive medications. A week later, she was presented to a peripheral maternity hospital with high blood pressure, low platelet count, and proteinuria. Ultrasound showed a single active fetus in a transverse lie with fetal parameters of 25 weeks and four days, expected fetal weight of 799 g, normal amniotic fluid volume with normal umbilical artery Doppler study (pulsatility index = 0.9), normal middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (33 in maximum at 1.1 multiples of the median) and normal ductus venosus study.

She received magnesium sulfate for severe preeclampsia and steroid cover for fetal lung maturity, preparing her for delivery. Due to severe thrombocytopenia, she was started on intravenous methylprednisolone and platelets transfusion. Despite this, her platelets dropped to 15 000/dL, then to 13 000/dL, and hematuria developed. As her liver functions remained normal, the diagnosis of HELLP syndrome seemed doubtful. Because of her past obstetric history, other causes of thrombocytopenia such as TTP, HUS, and systemic lupus erythematosus were considered. The multidisciplinary team, consisting of nephrologists, hematologists, rheumatologists, and obstetricians, discussed possible differential diagnoses. The blood film showed schistocytes, raising the possibility of TTP. To confirm TTP, disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13 (ADAMTS13) test was requested. In view of the patient’s deteriorating condition, further management was based on a provisional diagnosis of TTP. The patient’s high (21.6) lactate dehydrogenase to aspartate aminotransferase ratio also helped diagnose TTP.6

The patient was transferred to the high dependency unit and started on PTX as a part of the management of TTP. Three days later, her platelet level further dropped to 12 000/dL. She was transfused with fresh frozen plasma and two units of packed red blood cells. With repeat platelet at 25 000/dL, PTX was restarted. The patient had symptomatic severe pre-eclampsia, with headache, epigastric pain, and chest pain with desaturation. Both electrocardiogram and bedside echocardiography were normal, but troponin level was high (20 ng/L). She received intravenous bolus labetalol two times and was started on labetalol infusion in view of her high blood pressure.

It was difficult to make the crucial decision, of whether to continue or terminate the pregnancy. At that time, we were unable to confirm TTP without ADAMTS13 result, and unable to exclude severe preeclampsia. With the patient’s condition rapidly deteriorating, the obstetrician decided for immediate delivery by cesarean section at 26 weeks gestation. The patient’s platelet count had risen to 46 000/dL at the time of delivery. A live baby girl weighing 730 g, with normal cord pH was delivered.

After the delivery, the patient was returned to the high dependency unit and treated with magnesium sulfate and labetalol infusion. Methylprednisolone was continued. Laboratory results improved dramatically 48 hours post-delivery, platelets rised to 110 000/dL without PTX. Though her final diagnosis was severe preeclampsia with HELLP syndrome, we could not rule out TTP as the ADAMTS13 test result was still pending. The patient was discharged home in a good condition on the fourth day of delivery and prescribed oral labetalol 200 mg twice per day, oral prednisolone, and clexane for thromboprophylaxis.

Ten days after delivery, her platelet count dropped to 18 000 /dL, and she was given three sessions of fresh frozen plasma therapy within the next two months by which time her steroids were tapered and stopped. Currently, she is not on any medications. Her daughter was discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit two months after the delivery, with a weight of 3.4 kg and in good condition, without any neurological sequelae.

One month after delivery, the ADAMTS13 test results arrived, indicating the ADAMTS13 antibodies at 4.8 U/mL (normal < 12 U/mL), ADAMTS-13 activity at 0.09 IU/mL (normal = 0.40–1.30 IU/mL), and ADAMTS13 antigen at 0.03 IU/mL (normal = 0.41–1.41 IU/mL), thus confirming congenital TTP.

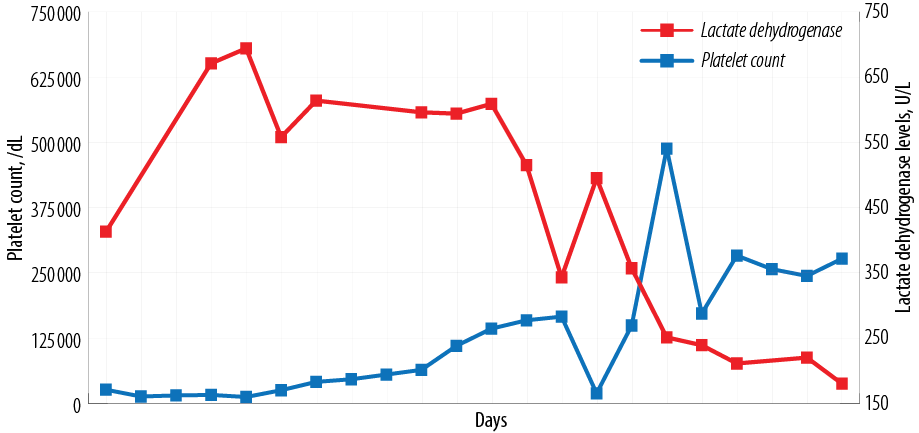

The variations in our patient’s platelet count and lactate dehydrogenase levels over time are shown in Figure 1. The various laboratory parameters in TTP, HELLP, and our patient are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1: Timeline of patient events with platelet and lactate dehydrogenase levels.

Figure 1: Timeline of patient events with platelet and lactate dehydrogenase levels.

Table 1: The differences in the clinical and laboratory findings between typical cases of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)/preeclampsia versus our patient.

|

Pregnancy specific

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Thrombocytopenia

|

Very low platelets

|

Low platelets

|

Very low platelets

|

|

Hemolysis on peripheral blood smear

|

Schistocytes ++

|

Schistocytes ++

|

Schistocytes ++

|

|

ADAMTS13 levels

|

Severely reduced

|

Slightly reduced to normal

|

Severely reduced

|

|

Liver enzymes

|

Normal

|

High

|

Normal

|

|

PT/PTT

|

Normal

|

High

|

Normal

|

|

Fibrinogen

|

Normal

|

Decrease

|

Normal

|

HELLP: hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count; ADAMTS13: disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13; PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time.

Discussion

TTP diagnosis is difficult in pregnancy due to clinical overlap with other pregnancy-related problems such as severe preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, gestational thrombocytopenia, and HUS.7 The co-existence of preeclampsia/ HELLP with TTP was estimated by Martin et al,4 to occur in about 17% of cases in his case series on 166 patients, with a higher maternal mortality rate than in pure TTP (44% vs. 21%), possibly due to delay in diagnosis or initiation of PTX.

Hereditary TTP is rare with one in 100 000 population, constituting < 5% of all TTP cases. When TTP manifests first time during pregnancy, the likelihood of hereditary TTP is much higher (24% as per the French thrombotic microangiopathy national registry and 66% as per the UK TTP registry).6,8 Hereditary TTP has always been associated with serious complications in pregnancy.9 The maternal and perinatal prognosis of hereditary TTP in pregnancy continues to be poor.10 Kasht et al,11 found that 97% of hereditary TTP patients had serious complications during one or more pregnancies, with early gestational age at presentation (22 weeks), high maternal mortality (16%), and high stillbirth rate (32 to 44%).4

Our patient had a good outcome in comparison to those reported in the literature. She had presented with features of TTP (which went unrecognized) in her first pregnancy and had a bad perinatal outcome. In the current pregnancy, she manifested the features of TTP at around the same gestational age (~ 25 weeks). However, with careful evaluation and multidisciplinary approach, we managed to save the patient and her baby.

Conclusion

Hereditary TTP occurring the first time in pregnancy has a high likelihood of stillbirth (approximately 70%), especially if it occurs before 28 weeks of gestation.6 If we had failed to recognize TTP with the superimposed preeclampsia in this pregnancy, the outcome would have been catastrophic. Managing this patient in a tertiary setup with multidisciplinary input made the difference in the outcome.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

references

- 1. Chang JC. TTP-like syndrome: novel concept and molecular pathogenesis of endotheliopathy-associated vascular microthrombotic disease. Thromb J 2018 Aug;16:20.

- 2. Moake JL. Thrombotic microangiopathies. N Engl J Med 2002 Aug;347(8):589-600.

- 3. George JN. Clinical practice. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 2006 May;354(18):1927-1935.

- 4. Martin JN Jr, Bailey AP, Rehberg JF, Owens MT, Keiser SD, May WL. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in 166 pregnancies: 1955-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008 Aug;199(2):98-104.

- 5. Tsai HM. Pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Int J Hematol 2010 Jan;91(1):1-19.

- 6. Moatti-Cohen M, Garrec C, Wolf M, Boisseau P, Galicier L, Azoulay E, et al; French Reference Center for Thrombotic Microangiopathies. Unexpected frequency of Upshaw-Schulman syndrome in pregnancy-onset thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2012 Jun;119(24):5888-5897.

- 7. Savignano C, Rinaldi C, De Angelis V. Pregnancy associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: practical issues for patient management. Transfus Apher Sci 2015 Dec;53(3):262-268.

- 8. Scully M, Thomas M, Underwood M, Watson H, Langley K, Camilleri RS, et al; collaborators of the UK TTP Registry. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and pregnancy: presentation, management, and subsequent pregnancy outcomes. Blood 2014 Jul;124(2):211-219.

- 9. Fuchs WE, George JN, Dotin LN, Sears DA. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Occurrence two years apart during late pregnancy in two sisters. JAMA 1976 May;235(19):2126-2127.

- 10. Kremer Hovinga JA, George JN. Hereditary thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 2019 Oct;381(17):1653-1662.

- 11. Kasht R, Borogovac A, George JN. Frequency and severity of pregnancy complications in women with hereditary thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol 2020 Nov;95(11):E316-E318.