Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri, is identified by features of raised intracranial pressure (ICP), normal neuroimaging with elevated cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure (CSFOP) in the background of normal CSF components.1

Headache that worsens in the morning, pulsatile tinnitus, and vision abnormalities are among most common symptoms of IIH. Single or multiple cranial nerve palsies may also occur, as elevated ICP can lead to cranial nerve traction and compression. Sixth cranial nerve palsy, a marker of raised ICP, is seen in about 10–50% of children and 12% of adults with IIH. Rarely, cranial nerves (CNs) III, IV, VII, IX, and XII may also be involved.2 However, the occurrence of six CN palsies simultaneously (II, III, VI, VII, IX, and X) in the context of IIH—as in the current case—is extremely rare.

Case Report

A 32-year-old Indian woman with no known comorbidities and a body mass index of 20.8 kg/m2 presented to the neurology clinic with the complaint of a two-week-long headache that was dull, aching, holocranial, and continuous, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia, with no aggravating or relieving factors. A week after the headache began, she developed drooping of the left eyelid accompanied by horizontal double vision, especially for distant objects. She experienced difficulty in swallowing solids and liquids or sipping with a straw, though she could chew food without difficulty. The patient had no nasal regurgitation or hoarseness of voice. She had no history of migraine headache, oral contraceptive intake, recent illness, fever, seizures, altered sensorium, or trauma. She had regular menstrual cycles with stable hemodynamics at the time of the assessment.

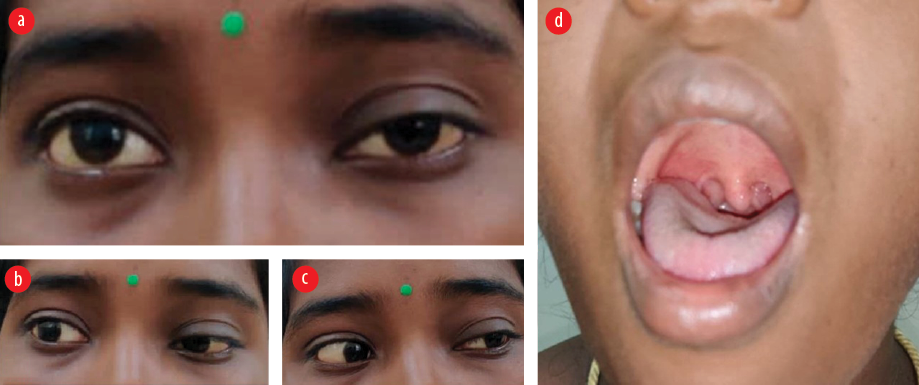

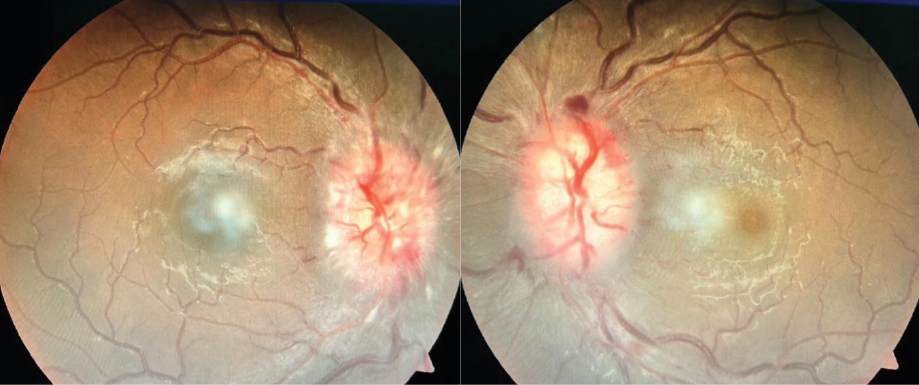

During the neurological assessment, she was alert and had normal higher mental functions with no signs of meningeal irritation. Her muscle tone, motor system, reflexes, sensory system, coordination, and gait were normal. CN examination revealed partial palsy of the left third CN which manifested as partial ptosis of the left eyelid [Figure 1a]. The pupils were 3–4 mm in size and reacted sluggishly to light. Bilateral lateral gaze restriction of eye movements was noted with no nystagmus or skew deviation suggestive of bilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy [Figure 1 b and c]. Bilateral facial weakness was observed in the form of weak eye closure, reduced frontal creasing, nasolabial folds, and inability to hold air in the mouth or blow a whistle. Facial sensations were preserved on both sides with a normal jaw opening and a midline tongue. The uvula was deviated to the left [Figure 1d], with an absent gag reflex on the right side suggestive of right 9th and 10th CN palsies. The examination of the fundus revealed bilateral papilledema was also suggestive of 2nd CN palsy [Figure 2]. The shrugging of her shoulders was bilaterally symmetrical, and her hearing was normal.

Figure 1: (a) Partial ptosis of left eyelid in primary gaze. (b and c) Lateral gaze restriction. (d) Uvula deviated to left side suggestive of right 9th and 10th cranial nerve palsies.

Figure 1: (a) Partial ptosis of left eyelid in primary gaze. (b and c) Lateral gaze restriction. (d) Uvula deviated to left side suggestive of right 9th and 10th cranial nerve palsies.

Figure 2:Fundoscopy showing bilateral papilledema, suggestive of 2nd cranial nerve palsy.

Figure 2:Fundoscopy showing bilateral papilledema, suggestive of 2nd cranial nerve palsy.

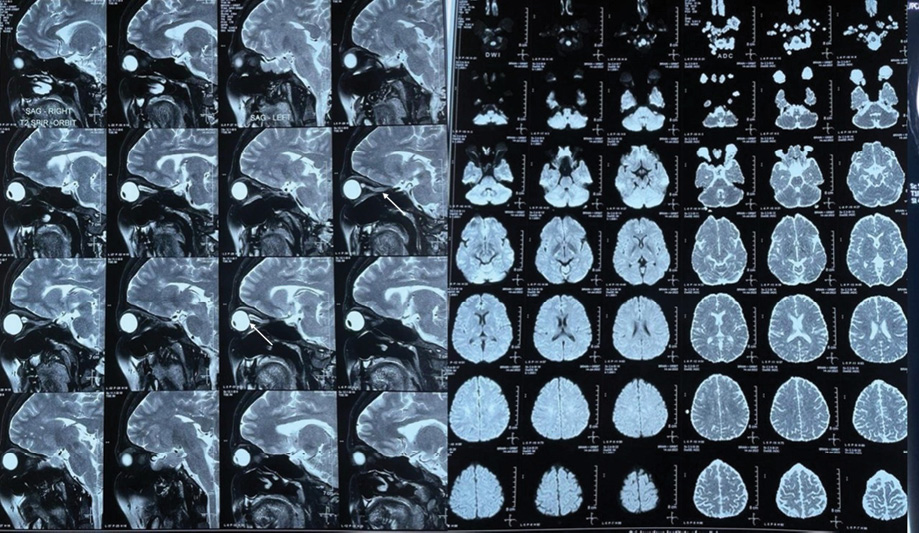

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain with magnetic resonance venography (MRV) revealed tortuous bilateral optic nerves with a mild bulge of the optic nerve head at the optic disc; these findings were consistent with raised ICP [Figure 3]. Lumbar puncture (LP) with the patient in the lateral decubitus position revealed a CSFOP of 320 mm H2O (standard reference interval: up to 250 mm H2O). The cytological and chemical results of LP were within the normal range: white blood cells 2 (lymphocytes 100%), protein 20.1 mg/dL, and glucose 79 mg/dL. No clinical or radiological features were suggestive of Addison’s or Cushing’s syndrome, and serology was negative. As the patient’s condition fulfilled modified Dandy criteria for definite IIH, she was started on a cerebral decongestant acetazolamide 250 mg twice daily along with topiramate 50 mg once at night for headache.

Figure 3: MRI of the brain showing tortuous bilateral optic nerves with a mild bulge of the optic nerve head at optic disc with hypoplastic left transverse sinus.

Figure 3: MRI of the brain showing tortuous bilateral optic nerves with a mild bulge of the optic nerve head at optic disc with hypoplastic left transverse sinus.

During her hospital stay, the patient showed dramatic improvement in headache and in palsies of the 7th, 9th, and 10th CNs. At a six-month routine follow-up, her papilledema and all the CN palsies were found to be completely resolved.

Discussion

In the current case, after eliminating possible secondary causes, only the features suggestive of raised ICP remained. Thus, the most likely diagnosis for our patient’s presentation was IIH according to modified Dandy criteria.3 This diagnosis was further supported by the markedly elevated CSFOP and improvement upon receiving acetazolamide therapy.

IIH affects both children and adults, with a yearly incidence of approximately one to two cases per 100 000 population.4 While age is no bar to presentation of IIH, this condition is observed more among obese women of childbearing age with an estimated prevalence of four to 21 cases per 100 000 population.5

IIH can be described by various imaging findings such as perioptic nerve sheath distention, vertical buckling of the optic nerve, globe flattening, optic nerve head protrusion, and an empty sella tursica.2 Other differential diagnoses include neurosarcoidosis, Lyme disease, and Bell’s palsy. While the definite pathophysiology of IIH is not clear, it possibly involves CSF production and absorption and cerebral venous pressure elevation.2

Headache, pulsatile tinnitus, brief visual obscurations, and vision loss are the most typical symptoms of IIH.1 Also, in a case-control study, the most common symptoms reported by IIH patients were headache (94%), transient visual obscuration (68%), pulsatile tinnitus (58%), photopsia (54%), diplopia (38%), vision loss (30%), and retrobulbar pain on eye movements (22%).6 In addition to these classical signs of IIH, patients may present with multiple CN palsies as a false localizing sign, the most common being unilateral or bilateral 6th CN palsy.7 Rare cases of association of IIH with involvement of the right second, third, sixth, and left seventh CNs have been reported.8 However, the association of IIH with bilateral multifocal CN palsies as observed in our case report has not been published to date to the best of our knowledge. Awareness that signs may be false localizing has implications for diagnostic investigations.

Ophthalmological evaluation for IIH should include fundoscopy, optical coherence tomography, and perimetry as it aids in early diagnosis and in monitoring response to therapy on follow-up. Neuroimaging with LPCSFOP further aids in confirming the diagnosis.5

Cases of IIH with third cranial nerve palsy should be investigated for possible pupillary involvement.9 Compression in the subarachnoid space in the setting of elevated ICP appears to be the most likely mechanism of involvement of the third nerve (and other CNs). The reversal of oculomotor palsy after serial lumbar punctures establishes its link to elevated ICP.

A prospective study of 724 patients with recurrent headaches used MRV and found that 67.8% of migraine patients had IIH without papilledema and 6.7% had bilateral transverse sinus stenosis after LP. These findings suggest that migraine patients with bilateral transverse sinus stenosis on cerebral MRV should have a LP to rule out IIH without papilledema.10

The main goal of therapy is to protect vision and reduce disabling symptoms. IIH is commonly managed with acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. Vomiting, diarrhea, renal stones, and aplastic anemia are the most common adverse effects associated with acetazolamide. Topiramate, another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, is used to manage headache and to reduce ICP. Topiramate additionally suppresses appetite and helps in promoting weight loss in obese patients. Furosemide, a loop diuretic can also be considered. Methyl prednisone, 1 g per day along with acetazolamide may be used in the short-term management of IIH, especially in fulminant IIH which threatens vision loss. Due to the adverse effects such as weight gain and fluid retention, methyl prednisone is not recommended for long-term management of IIH.

One case in the literature where methyl prednisone was used in an obese patient was that of a 40-year-old Hispanic woman with hypertension.2 She presented with typical IIH symptoms including those indicative of a right-sided CN VII palsy. The fundus examination revealed bilateral grade II papilledema. Imaging studies ruled out structural and obstructive lesions and LP results were unremarkable except for increased OP. Prednisone and acetazolamide were administered. Two days later, both her headache and facial nerve palsy were reported a significant improvement .2 As our patient showed a significant response to acetazolamide alone, steroids could be avoided.

Fourteen case reports of IIH with facial nerve palsy involvement are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Cases of idiopathic hypertension with multiple cranial palsies selected from the literature.

|

Hagberg and Sillanpää,11 1970

|

F

|

7

|

Unilateral CN VII and CN V

|

Headache and vomiting

|

Lumbar puncture and dexamethasone

|

|

Chutorian et al,12 1977

|

M

|

12

|

Unilateral CN VII

|

Bifrontal headache, drooping of the left side of the face, tearing from the left eye, nausea, and vomiting

|

Lumbar puncture

|

|

F

|

11

|

|

Transfrontal headache, facial asymmetry,

|

|

|

F

|

14

|

|

intermittent bitemporal headache, right side face drooping, and right brow could not elevate

|

|

|

Snyder and Frenkel,13 1979

|

F

|

25

|

Unilateral CN VII and ophthalmoplegia

|

Not available

|

Lumbar puncture and dexamethasone

|

|

Couch et al,14 1984

|

M & F

|

≤ 14

|

Unilateral CN VII and CN V

|

Headache, nausea and vomiting, visual disturbances, neck pain, unsteady gait, intermittent paresthesia, and swishing

noise in both ears which correlated with an audible generalized cranial bruit

|

Lumbar puncture

|

|

Kiwak and Levine,15 1984

|

F

|

28

|

Diplegic CN VII

|

Pressure like bifrontal headaches and

decreased peripheral vision

|

Lumbar puncture, prednisone, acetazolamide, lumboperitoneal shunt

|

|

Agarwal et al,16 1989

|

F

|

29

|

Unilateral CN VII, CN VI, and partial CN III

|

Not available

|

Lumbar puncture,

dexamethasone,

glycerol syrup

|

|

Zachariah et al,17 1990

|

F

|

29

|

Unilateral CN VII

|

Headaches, numbness of the right

side of the face, altered taste sensation, and tingling and weakness of the right arm and right leg

|

Lumbar puncture, prednisone, and acetazolamide

|

|

Bakshi et al,18 1992

|

F

|

23

|

Diplegia CN VII and CN V

|

Bifrontal headache, vomiting, and loss of vision

|

Lumboperitoneal shunt

|

|

Davie et al,19 1992

|

F

|

25

|

CN VII and CN VI

|

Bifrontal headaches, nausea, and

vomiting

|

Lumbar puncture

|

|

Capobianco et al,20 1997

|

F

|

12

|

Unilateral CN VII

|

Bifrontal headaches and right-sided facial drooping

|

Prednisone

|

|

F

|

36

|

Unilateral CN VII

|

Severe throbbing headaches, pulsatile tinnitus, blurred vision in the left eye, painless horizontal diplopia, and

right-sided facial pain

|

Optic nerve sheath

decompression

|

|

Brackmann and Doherty,21 2007

|

M

|

8

|

Unilateral CN VII

|

Right-sided facial palsy

|

Acetazolamide, prednisolone, and serial lumbar punctures

|

|

Soroken et al,22 2015

|

F

|

13

|

Unilateral CN VI and contralateral CN VII

|

Diplopia and horizontal strabismus of the left eye

|

Lumbar puncture and acetazolamide

|

|

Samara et al,2 2019

|

F

|

40

|

Unilateral CN VII

|

Bifrontal headache

|

Prednisone and acetazolamide

|

CN: cranial nerve.

Bilateral papilledema is a feature of IIH, and optical coherence tomography imaging is an objective, noninvasive, and reproducible technique for diagnosing and monitoring it. The benefits of octreotide and somatostatin analogues in IIH are still being evaluated. Patients who do not tolerate or improve with medical management may need surgical management such as optic nerve sheath fenestration and CSF diversions (lumboperitoneal or ventriculoperitoneal shunting). Transverse venous sinus stenting is one of the cutting-edge surgical treatments for IIH with promising outcomes.8

Conclusion

For women of reproductive age who present with headache and multiple cranial nerve palsies, IIH should be included in the differential diagnosis. IIH is an exclusionary diagnosis and neuroimaging should be conducted to rule out any secondary causes for raised ICP. In this paper, we have sought to raise clinicians’ awareness of the potential for IIH in presentations of multiple cranial nerve palsies, as it is rarely described in the pathophysiology of IIH.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Written consent has been obtained from the patient.

references

- 1. Dafallah MA, Habour E, Ragab EA, Shouk ZM, Izzadden M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension with multiple cranial nerve palsies in 10 years old thin Sudanese boy: case report. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatr Neurosurg 2021;57(1):85.

- 2. Samara A, Ghazaleh D, Berry B, Ghannam M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension presenting with isolated unilateral facial nerve palsy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2019 Apr;13(1):94.

- 3. Dandy WE. Intracranial pressure without brain tumor: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Surg 1937 Oct;106(4):492-513.

- 4. Wakerley BR, Tan MH, Ting EY. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cephalalgia 2015 Mar;35(3):248-261.

- 5. Sheoran A, Dabas R, Malhotra A, Singh P. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension with multiple cranial nerve involvement: a clinical enigma. Journal of Advanced Research in Medicine 2019;6(2):20-22.

- 6. Menon RN, Radhakrishnan K. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: are false localising signs other than abducens nerve palsy acceptable? Neurol India 2010;58(5):683-684.

- 7. Raman SP, Velayutham SS, Jeyaraj KM, Kumar MS, Mugundhan K. Polyradiculopathy and multiple cranial nerve palsies - rare manifestations of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Neurol India 2021;69(1):170-173.

- 8. González-Andrades M, García-Serrano JL, González Gallardo MdelC, Mcalinden C. Multiple cranial nerve involvement with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. QJM 2016 Apr;109(4):265-266.

- 9. Rezazadeh A, Rohani M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension with complete oculomotor palsy. Neurol India 2010;58(5):820-821.

- 10. Suzuki H, Takanashi J, Kobayashi K, Nagasawa K, Tashima K, Kohno Y. MR imaging of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001 Jan;22(1):196-199.

- 11. Hagberg B, Sillanpää M. Benign intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Review and report of 18 cases. Acta Paediatr Scand 1970 May;59(3):328-339.

- 12. Chutorian AM, Gold AP, Braun CW. Benign intracranial hypertension and Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med 1977 May;296(21):1214-1215.

- 13. Snyder DA, Frenkel M. An unusual presentation of pseudotumor cerebri. Ann Ophthalmol 1979 Dec;11(12):1823-1827.

- 14. Couch R, Camfield PR, Tibbles JA. The changing picture of pseudotumor cerebri in children. Can J Neurol Sci 1985 Feb;12(1):48-50.

- 15. Kiwak KJ, Levine SE. Benign intracranial hypertension and facial diplegia. Arch Neurol 1984 Jul;41(7):787-788.

- 16. Agarwal MP, Mansharamani GG, Dewan R. Cranial nerve palsies in benign intracranial hypertension. J Assoc Physicians India 1989 Aug;37(8):533-534.

- 17. Zachariah SB, Jimenez L, Zachariah B, Prockop LD. Pseudotumour cerebri with focal neurological deficit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990 Apr;53(4):360-361.

- 18. Bakshi SK, Oak JL, Chawla KP, Kulkarni SD, Apte N. Facial nerve involvement in pseudotumor cerebri. J Postgrad Med 1992;38(3):144-145.

- 19. Davie C, Kennedy P, Katifi HA. Seventh nerve palsy as a false localising sign. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992 Jun;55(6):510-511.

- 20. Capobianco DJ, Brazis PW, Cheshire WP. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and seventh nerve palsy. Headache 1997 May;37(5):286-288.

- 21. Brackmann DE, Doherty JK. Facial palsy and fallopian canal expansion associated with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Otol Neurotol 2007 Aug;28(5):715-718.

- 22. Soroken C, Lacroix L, Korff CM. Combined VIth and VIIth nerve palsy: consider idiopathic intracranial hypertension!. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 2016 Mar;20(2):336-338.