On 30th January 2020, the World Health Organization, reported the discovery of the novel coronavirus and designated it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern under the International Health Regulation.1 The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a high percentage of viral infection-related deaths as well as psychological and emotional consequences.2 Healthcare workers (HCWs) had to respond to this pandemic by becoming actively involved in the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 patients, risking exposure to the novel virus and thereby bearing the brunt of physical, psychological, and behavioral health issues.3

It has become evident that extreme pressure while working affects the physical, emotional, and mental health of the HCWs.4 Furthermore, it has been reported that most HCWs experienced depression, insomnia, stigma, and frustration during the pandemic. Southeast Asia had lower rates of anxiety, depression, and sleeplessness compared with other regions, as evident from comparing two meta-analyses.5 The discrepancy is compounded when contrasted with South European nations like Spain, France, Italy, and Greece. Southeast Asia’s lower prevalence rates may be attributed to the region’s recent experience with epidemics and the use of early interventions similar to those in China and East Asia to improve HCWs' mental health.5

According to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, India was the most impacted country in terms of confirmed COVID-19 cases, after only the USA, Brazil, Russia, Spain, and the UK.6 Among the Indian population, stress, anxiety, and depression were reported to be present among 28.9%, 35.6%, and 17.0% respectively, during the COVID-19 lockdown.7 The mental health issues experienced by HCWs impacted competency and motivation, increasing the risk of emotional exhaustion and hindering the healthcare response to COVID-19.8 A cross-sectional study from India identified the prevalence of anxiety (23.9%) and depression (20%) among HCWs.9 However, to date, there is no robust evidence on the magnitude of stress, anxiety, and depression among HCWs in India and its context as a mental health problem in the Indian healthcare system. Therefore, the purpose of this mixed-methods systematic review was to measure the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of HCWs in India and to identify the contributing factors to contextualize evidence to inform policies to meet the mental health needs of HCWs in the future.

Methods

This review adopted a results-based convergent approach incorporating quantitative and qualitative data.10,11 We began with quantitative survey data to determine the prevalence of mental health problems faced by HCWs in India during the COVID-19 pandemic and integrated quantitative (meta-analysis) and qualitative data (themes) to identify the contributing factors and coping strategies across six domains: individuals, family, peers, community, health services, and the wider society.

This systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021236500) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Meta-analysis (PRISMA) framework to report this systematic review.

Search strategy

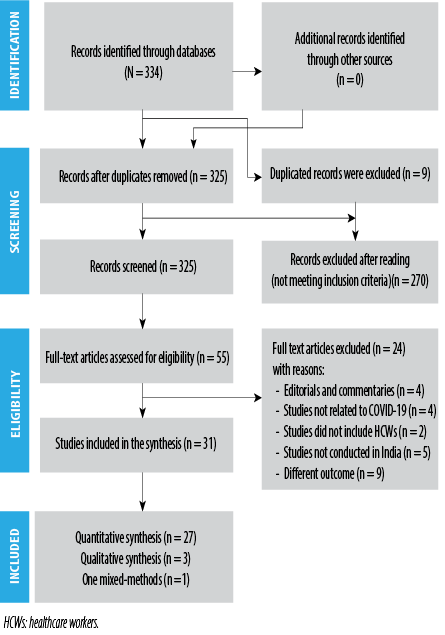

The search was limited to papers published in the English language until 28 February 2022. An electronic search of four databases (PubMed-Medline, CINAHL, Web of Science, and ProQuest) was conducted to identify peer-reviewed articles focusing on the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of HCWs in India. The search process is reported using the PRISMA diagram [Figure 1]. Initially, each database was searched, and the title and abstract were screened independently by two reviewers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria [Table 1]. Subsequently, the full text of each article was thoroughly reviewed independently by two reviewers. Reference lists of relevant studies were examined to identify the additional studies. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Figure 1: Study selection process.

Figure 1: Study selection process.

Table 1: Study eligibility criteria.

|

Population

|

Doctors, nurses, and paramedical health personnel (technicians and physiotherapists)

|

Studies that included children and the general population

|

|

Study type

|

Descriptive, cross-sectional, observational, qualitative, and mixed-method studies

|

Intervention studies, systematic reviews, commentaries, literature reviews, and letters

|

|

Outcome

|

Anxiety, depression, and stress

|

|

HCWs: healthcare workers.

Data extraction

The studies that met the inclusion criteria were exported from each database into an Excel sheet. Two reviewers independently performed the data extraction using the piloted data extraction form. The form included information on the authors, year of publication, study design, sample size, outcomes, and study findings.

For the included qualitative studies, the same two reviewers independently reviewed them and conducted line-by-line coding of the findings to identify themes. Common themes were derived after summarizing the findings, and supporting quotes were drawn from the qualitative studies. Any disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved through consultation with a third reviewer.

Critical appraisal

The methodological quality of the included quantitative and qualitative studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment instruments,12,13 and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools Version 2018 as appropriate.14 The first and second reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies. Any discrepancies between the two authors were resolved in a discussion with a third reviewer. The quality assessment is presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.15–45

Table 2: Critical appraisal of quantitative studies based on the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for cross-sectional studies.

|

Chatterjee et al,15 2020

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Wilson et al,16 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Dordi et al,17 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Suryavanshi et al,18 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Khanam et al,19 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Chew et al,20 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Rathore et al,21 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

No

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Patel et al,22 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Rehman et al,23 2020

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Uvais et al,24 2020

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Gupta et al,25 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Chauhan et al,26 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Das et al,27 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Dharra et al,28 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Include

|

|

Garg et al,29 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Khan et al,30 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Jakhar et al,31 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Mishra et al,32 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Raj et al,33 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Chatterji et al,34 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Sharma et al,35 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Unclear

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Gupta et al,36 2020

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Singh et al,37 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Sukumaran et al,38 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Sharma S et al,39 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Sharma V et al,40 2021

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

Table 3: Critical appraisal of qualitative studies based on the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for qualitative studies.

|

Chakma et al,42 2021

|

Yes (research methodology was mentioned as qualitative research)

|

Yes

|

Yes (telephonic interview)

|

Yes (thematic analysis)

|

Yes

|

No

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

|

Golecha et al,43 2021

|

Yes

(The study followed a qualitative approach applying in-depth one-on-one interviews)

|

Yes

|

Yes (telephonic interview)

|

Yes (Colaizzi’s protocol was followed)

|

Yes

|

No

|

Unclear

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Include

|

Table 4: Critical appraisal of mixed methods study based on Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, version 2018.

Data synthesis

The data synthesis was conducted in three stages following the framework described in another study.46 Firstly, a meta-analysis was performed using Stata software (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.) to determine the pooled prevalence of anxiety, stress, and depression among the HCWs during the pandemic, based on quantitative studies. A heterogeneity (I2) statistic between estimates was assessed, which describes the percentage variation. I2 value > 75% indicates a high heterogeneity. We anticipated significant I2 and used the random effects model for meta-analysis. Forest plots were generated for each outcome, and the results were presented as pooled prevalence with a 95% CI. Next, we conducted a thematic synthesis of the findings from the qualitative studies. Finally, a conceptual matrix was utilized to integrate the findings of quantitative and qualitative synthesis. This integration provided a clear explanation of the factors related to individuals, family, peers, community (living and working conditions), health services, and wider society that influenced the mental health of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Studies selection

A total of 334 studies were retrieved from four databases [Figure 1]. After removing 9 duplicated records, the remaining 325 studies underwent title screening, resulting in the exclusion of 270 studies. The remaining 55 studies were assessed against the eligibility criteria, leading to the exclusion of 24 articles (four editorials and commentaries, four studies unrelated to COVID-19, two studies did not involve HCWs, five studies conducted outside of India, and nine studies including outcomes beyond the scope of this review). Finally, 31 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (27 quantitative studies, three qualitative studies, and one mixed-methods study). However, for meta-analysis, 26 studies were included (25 quantitative and one mixed-methods study). However, two studies reported the findings using mean and SD and were not included in the meta-analysis.19,23 For the qualitative synthesis, data from three qualitative studies and one mixed-methods study were incorporated.

Characteristics of the included studies

The review included a total of 10 043 HCWs as participants. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 78 years, and they were employed in both governmental and non-governmental organizations across various parts of India. The participants comprised nurses, doctors (including residents), paramedical staff, and support staff. Table 5 provides a summary of the included studies.

Table 5: Characteristics of included studies.

|

Chatterjee et al,15 2020, West Bengal

|

Online survey

|

Cross-sectional study

|

152 doctors

119 male

33 female

Mean age: 42.05 ± 12.19 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS)-21

|

34.9% were depressed and 39.5% and 32.9% had anxiety and stress, respectively

|

|

Wilson et al,16 2020,

India Nationwide (10 states and one union territory)

|

Online survey

|

Cross-sectional

survey

|

350 doctors and nurses

187 males

163 females

Age: 18–60 years

|

Depression,

anxiety, and

stress

|

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, and

Cohen’s perceived stress scale (PSS)

|

The prevalence (95% CI) of healthcare workers (HCWs) with high-level stress was 3.7% (2.2–6.2), depressive symptoms requiring treatment, and anxiety symptoms requiring further evaluation were 11.4% (8.3–15.2) and 17.7% (13.9–22.1), respectively

|

|

Dordi et al,17 2020,

Sir H.N. Reliance Hospital and Research Centre

|

Hospital-based survey

|

Hospital-based survey

|

280 (100 patient-facing and 100 non-patient facings) participants from the hospital

80 males

200 females

Age: 20–60 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and psychological distress

|

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Kessler, and Psychological Distress Scale

|

Depression (17%), anxiety (7.12%), and psychological distress (31.67%). There was a higher prevalence of distress among nurses than in doctors.

There was a significant difference in the depression scores of HCWs who were seeing patients versus HCWs not seeing any patients

|

|

Suryavanshi et al,18 2020,

Maharashtra

|

Online survey

|

Survey

|

197 HCWs including doctors, nurses, and paraclinical staff

96 males

101 females

|

Depression and anxiety

|

PHQ-9

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

|

Symptoms of depression (92, 47%), anxiety (98, 50%), and low quality of life (89, 45%). Odds of combined depression and anxiety were 2.37 times higher among single healthcare professionals compared to married (95% CI: 1.03–4.96).

Work environment stressors were associated with a 46% increased risk of combined depression and anxiety (95% CI: 1.15–1.85)

|

|

Khanam et al,19 2020,

Kashmir, India

|

Hospital-based online survey

|

Exploratory study

|

133 front-line HCWs including doctors, nurses, technicians, and others

74 males

59 females

Age: not specified

|

Stress and psychological impact

|

Self-reported stress questionnaire

Impact of Event Scale-Revised scale

|

Nurses had significantly more stress than doctors.

Stress was seen more in FHCWs working in the swab collection center as compared to those working in the other departments. The severe psychological impact was seen in 81 (60.9%) of FHCWs and was significantly more in males and married HCWs

|

|

Chew et al,20 2020,

Singapore and India

|

5 major hospitals from India and Singapore

|

A multi-national, multicenter study

|

426 HCWs from India including doctors, nurses, allied health staff, administrators, clerical staff, and maintenance workers.

Age: 25–35 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

DASS-21

|

The prevalence of depression in Indian HCWs was 53(12.4%), anxiety 73 (17.1%), stress 16(3.8%), and PTSD 31(7.3%)

|

|

Rathore et al,21 2020,

|

Online survey

|

Cross-sectional study

|

100 HCWs

69 males

31 females

Age: < 30–45 years

|

Anxietyand stress

|

Likert scale

Likert scale

|

72% of HCWs were concerned about the risk of infection, while 46% reported disruption in daily activities. 17% of HCWs were concerned about inadequate PPE and related challenges. 20% had inadequate knowledge and training about COVID. 16% of HCWs were anxious all the time, 11% feared all the time, and 12% had stress all the time while treating COVID patients

|

|

Patel et al,22 2020,

India

|

Tertiary care institutions in a western state of India

|

Online survey

|

302 HCW›S

189 males

113 females

Age: 21–60 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

DASS-21

PSS

|

101 (33.44%) HCWs reported low, 185 (61.26%) moderate, and 16 (5.30%) high levels of stress. Depression was reported by 56 (18.54%) subjects, 60 (19.87%) were found to have anxiety, and 50 (16.56%) reported having stress.

Perceived stress was significantly correlated with depression, anxiety, and stress

|

|

Rehman et al,23 2020,

|

Online survey

|

Online survey

|

403 total sample: 34 mental health professionals, 33 health professionals (doctors and nurses)

Average age: 28.95 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

DASS-21

|

The mean (SD) depression score of healthcare professionals was 10.79 (6.56) and that of mental health professionals was 6.76 (10.04).

The mean anxiety score was mean 12.55 (6.23) in health professionals and 5.65 (8.35) in mental health professionals.

The mean stress score in health professionals was 14.61 (7.85) and in mental health professionals was 9.29 (8.87)

|

|

George et al,45 2020,

Bangalore, India

|

Community Health Division, Baptist Hospital, Bangalore

|

A quantitative (QUAN) paradigm nested in the primary qualitative (QUAL) design

|

HCWs include doctors, nurses, paramedical, and support staff.

Out of 87 staff, 42 participated in the QUAL study, and 64 participated in the QUAN survey

40 males

24 females

Mean age: 34.6 ±10.7 years

|

Anxiety and stress

|

Likert scale

|

Hobbies (20.3%) and spending more time with family (39.1%) were cited as a means of emotional regulation in the QUAN survey.

QUAL findings: fear of death, guilt of disease transmission, anxiety about probable violence, stigma, and exhaustion were the major themes causing stress. Positive reframing, peer support, distancing, information seeking, response efficacy, self-efficacy, existential goal pursuit, value adherence, and religious coping were the coping strategies

|

|

Uvais et al,24 2020,

Kerala, India

|

Staff working in the Dialysis unit

|

Online survey

|

335 (dialysis technicians and dialysis nurses)

91 males

244 females

Age: 18–30 years

|

Stress

|

PSS

|

121 (36.1%) had high stress and the mean PSS-10 score was 17.72 (4.48)

|

|

Gupta et al,25 2020,

India

|

Online survey

|

Cross-sectional online study

|

368 (full-time practicing doctors, nurses, dentists, and paramedic staff)

168 males

200 females

Age: 30–60 years

|

Anxiety

|

GAD-7

|

Severe anxiety was observed among 7.3% (27/368) HCWs, whereas moderate, mild, and minimal anxiety was observed among 12.5% (46/368), 29.3% (108/368), and 50.8% (187/368), respectively

|

|

Chauhan et al,26 2021,

India

|

HCWs of two large tertiary care hospitals providing COVID-19 treatment

|

Cross-sectional

|

200 High COVID Exposure (HCE) HCWs

129 males

71 females

Age: 18–60 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

PHQ-9

GAD-7

IES-R

|

Stress symptoms were found in 23.5%, depressive symptoms in 17%, and anxiety symptoms in 10.85% among the HCE HCWs

|

|

Das et al,27 2021,

Andhra Pradesh

|

COVID-19 care settings

|

Cross-sectional survey

|

321 frontline HCWs (doctors and nurses)

168 males

153 females

Age: not specified

|

Stress

|

PSS-10

|

About 69.7% of the frontline, HCWs recorded higher perceived stress

|

|

Dharra et al,28 2021,

Uttarakhand

|

All India Institutes of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh.

|

Cross-sectional study

|

368 nurses

149 males

219 females

Mean age: 28.91 ± 3.68

|

Anxiety

|

GAD-7

|

The mean anxiety scores were 32.19 ± 4.53 and 3.82 ± 2.87 for female and male nurses. Age > 30 years (p = 0.003), diploma qualification (p < 0.001), and lack of training in handling COVID-19 patients (p = 0.003) were significant determinants of higher anxiety among nurses

|

|

Garg et al,29 2020,

India

|

COVID-19 exclusive hospital

|

Online cross-sectional survey

|

209 nurses

16 males

193 females

Age: 21–60 years

|

Anxiety and stress

|

GAD-7

PSS-10

|

65 (31.1%) participants had anxiety symptoms and 35.40% had moderate to high stress. The risk factors of anxiety and stress were working experience of

> 10 years (odds ratio [OR] = 3.36), direct involvement in the care of suspected/diagnosed patients (OR = 3.4), feeling worried about being quarantined/isolated (OR = 1.69), and high risk of being infected at the job (OR = 2.3)

|

|

Khan et al,30 2021,

Pan India

|

COVID ward and COVID intensive care unit

|

Cross-sectional study (online)

|

829 HCWs including doctors, nurses and other medical staff

475 males

354 females

Age: 19–64 years

|

Depression and anxiety

|

PHQ9

HAM-A

|

Anxiety and depression were significantly higher in doctors and staff nurses as compared to other medical staff.

64.7% of respondents had mild depression, 25.9% mild to moderate, and 9.4% moderate to severe depression. Anxiety was mild in 540 (65.1%), mild to moderate in 182 (22%) and moderate to severe in 107 (12.9)

|

|

Jakhar et al,31 2021,

Across the nation

|

Government health sectors

|

Cross-sectional survey (online)

|

450 HCWs (doctors and nurses)

216 males

234 females

Age: 31.6 ± 6.6 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

DASS – 21

|

The prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression among HCWs were 33.8, 38.9, and 43.6%, respectively

|

|

Mishra et al,32 2020,

Chhattisgarh, India

|

Dentists working in various regions of the Chhattisgarh

|

Cross-sectional survey (Online)

|

1253 dentists

607 males

646 females

Mean age: 28 ± 7.64 years

|

Stress

|

PSS

|

The mean PSS for dentists was 18.61 ± 6.87 in phase I and 20.72 ± 1.95 in phase II

No family time due to long working hours (90%) was the major stressor among dentists during phase I and concern about getting infected (83.3%) was identified as the most frequent stressor during phase II

|

|

Raj et al,33 2020,

India

|

Electronic Mail System

|

Cross-sectional study

|

Physicians n = 100, nurses n = 80, technical staff n = 20

Males: physicians 37.2%, nurses 15%, technical staff 57%

Females: physicians 62.8%, nurses 85%, and technical staff 43%

Mean age: doctors (35.54 ± 6.09), nurses (33.84 ± 7.87), and technical staff (32.16 ± 5.89)

|

Depression and anxiety

|

Structured questionnaire

|

Anxiety was seen in 55.65%, 48.54%, and 52.34% of physicians, nursing staff, and technicians of the study population while depression was evidently reported in 32.1%, 53.72%, and 42.7%, respectively

|

|

Chatterji et al,34 2021,

West Bengal, India

|

Diamond Harbour Medical College and Hospital

|

Cross-sectional study

|

N = 140 HCWs (56 doctors, 46 nurses, 20 ward staff, and 18 non-clinical staff)

61 males

79 females

Mean age: 37.67 ± 9.8 years

|

Stress

|

PSS-10

|

Low stress 29 (20.7%), moderate stress 102 (72.9%), and high stress 9 (6.4%) were reported by the HCWs.

Doctors had the highest level of anxiety. Younger age, higher education, female gender, and urban habitat were associated with a greater perception of anxiety

|

|

Sharma et al,35 2020,

Noida, UP

|

Super Specialty Paediatric Hospital and Post Graduate Teaching Institute

|

Cross-sectional study

|

150 HCWs

|

Depression,

anxiety, and stress

|

DASS-21

|

HCWs demonstrated a high prevalence of anxiety: 85/150 (56.7%), stress: 82/150 (54.7%), and depression: 72/150 (48.0%)

|

|

Gupta et al,36 2020,

Across India

|

Not specified

|

Cross-sectional study

|

1124 HCWs, including 749 doctors, 207 nurses, 135 paramedics, 23 administrators, and 10 supporting staff members.

718 males

406 females

Age: not specified

|

Depression

|

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

|

One-third of the HCWs reported anxiety and depressive symptoms. The risk factors for anxiety symptoms were female gender, younger age, and job profile (nurse), and for depressive symptoms younger age and working at a primary care hospital

|

|

Singh et al,37 2021,

New Delhi, India

|

Hospitals providing Covid care

|

Cross-sectional online survey

|

348 HCWs

194 males

154 females

Mean age: 31.8 years

|

Depression and anxiety

|

PHQ-9

GAD-7

|

Depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms were present in 54%, 44.3%, and 54.6% of HCWs

|

|

Sukumaran et al,38 2021,

Kerala

|

Online survey mode

|

Cross-sectional survey

|

544 HCWs (doctors, nurses, and paramedical staff)

186 males

358 females

Age: 22–78 years

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

DASS-21

|

9.7% of HCWs had mild depression and 13.3% had moderate-to-severe depression. While 4% had mild anxiety and 3.5% had moderate-to-severe anxiety, about 6.8% had mild stress and 6.4% had moderate-to-severe stress. Emotional and social support from higher health authorities are a significant protective factor against stress and depression

|

|

Sharma S et al,39 2021,

Covid care institutes of India

|

Government tertiary healthcare institutes

|

Cross-sectional online survey

|

354 nurses

241 males

113 females

Mean age: 28.78 ± 4.3 years

|

Depression and anxiety

|

HADS

|

Of 354 nurses, 12.1% were suffering from anxiety while 14.7% had depression

|

|

Sharma V et al,40 2021,

India

|

Online survey

|

Cross-sectional study

|

100 male Orthopedic surgeons

Age: 30–60 years

|

Anxiety

|

GAD-7

|

Severe anxiety scores were observed in 8%; moderate, mild, and minimal anxiety was observed in 12%, 27%, and 53% of surgeons

|

|

Yadav et al,41 2021,

India

|

Private practitioners’ clinics

|

Internet-based survey

|

120 private practitioners

99 males

21 females

Age: 29–50 or more

|

Depression, anxiety, and stress

|

DASS-21

|

Severe depression was in 35% and 13.3% of HCWs had extremely severe depression. Severe and extremely severe anxiety was noticed in 31.66% and 15% of HCWs. Severe and extremely severe stress was found in 30% and 12.5% of private practitioners

|

|

Chakma et al,42 2021,

10 States across India

|

A multicenter study conducted in 10 States across India

|

A qualitative study (Telephonic interviews)

|

111 HCWs (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, ambulance workers, community workers, housekeeping staff, security guards, stretcher-bearers, sanitation workers, laboratory staff, and hospital attendants)

51 males

60 females

Age: 20–30 years

|

Psychosocial challenges faced and coping strategies adopted by HCWs

|

Interview questionnaire

|

HCWs report major changes in the work-life environment. Family-related issues. Stigma from the community and peers. Coping strategies included peer and family support and positive experiences

|

|

Golecha et al,43 2021,

Gujarat

|

Primary and community health centers of rural Gujarat

|

A qualitative study (In-depth one-to-one interviews)

|

19 Rural primary care providers (12 doctors and 7 nurses)

14 males

5 females

Average age: 35 years

|

Perspectives and lived experiences of PCPs during COVID-19

|

Semi-structured questionnaire

|

The themes identified were lack of preparedness, vulnerability, management, workload, training, equipment and supplies, organizational factors, psychosocial support, and health system resource. Resilience mechanisms were recognition from communities and authorities, professional and family networks, and self-regulatory behaviors such as faith-based activities and wellness and motivation activities

|

Assessment of publication bias

The publication bias among the included quantitative studies was assessed using Egger’s test which indicated no evidence of publication bias

(p > 0.05) [Table 6].

Table 6: Results of Egger’s test for publication bias.

|

Depression

|

|

Slope

|

0.1327 (-0.1901–0.4557)

|

0.393

|

|

Bias

|

3.4729 (-2.9008–9.8468)

|

0.262*

|

|

Anxiety

|

|

Slope

|

0.2279 (-0.0286–0.4845)

|

0.079

|

|

Bias

|

1.2759 (-3.4444–5.9963)

|

0.579*

|

|

Stress

|

|

Slope

|

0.6358 (0.1861–1.0855)

|

0.009

|

*not significant, p > 0.05.

Findings from the quantitative studies

DEPRESSION

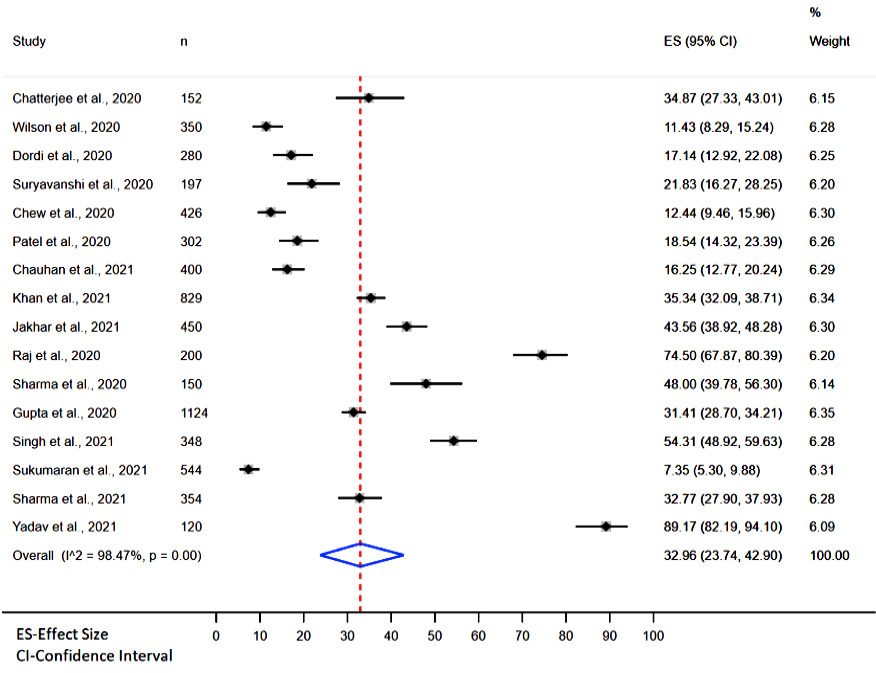

Sixteen studies reported the prevalence of depression.15–18,20,22,26,30,31,33,35–39,41 Other characteristics of the study findings are presented in Table 5. The calculated pooled prevalence by the random effect model was 32.96% (95% CI: 23.74–42.90, I2 = 98.47%; p < 0.00) [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Pooled prevalence of depression.

Figure 2: Pooled prevalence of depression.

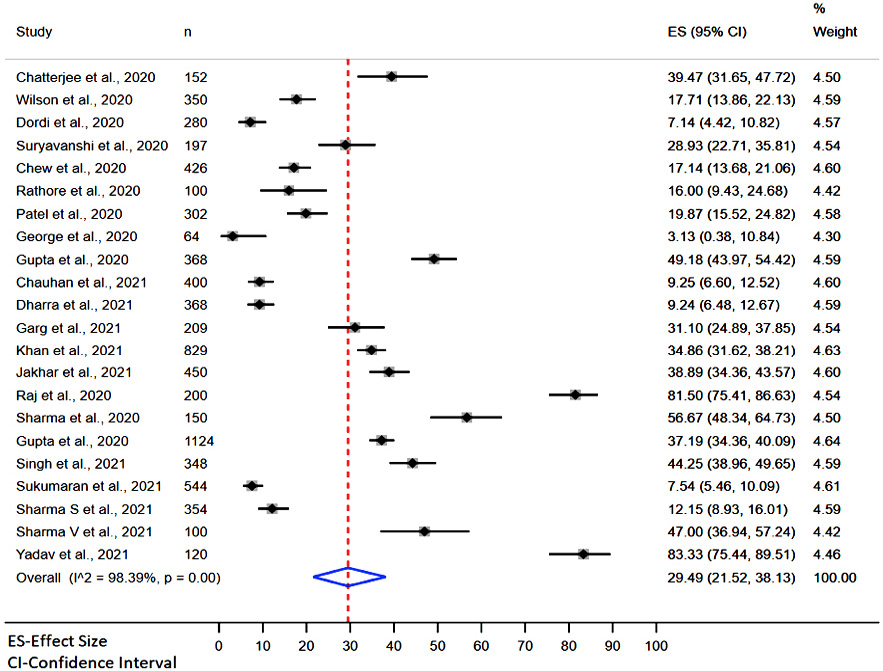

ANXIETY

Twenty-two studies (21 quantitative studies and one mixed method study) reported the prevalence of anxiety among HCWs.15–18,20–22,25,26,28–31,33,35–41,45 Other characteristics of the study findings are presented in Table 5. The pooled prevalence of anxiety [Figure 3] was calculated using the random effect model, and it was found to be 29.49% (95% CI: 21.52–38.13, I2 = 98.39%; p < 0.00) [Figure 3].

Figure 3: Pooled prevalence of anxiety.

Figure 3: Pooled prevalence of anxiety.

Stress was reported in 16 studies (15 quantitative studies and one mixed method study.15,16,20–22,24, 26,27,29,31,32,34,35,38,41,45 Other characteristics of the study findings are presented in Table 5. The pooled prevalence of stress was 33.47% (95% CI: 18.45–50.43, I2 = 99.36%; p < 0.00), as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Pooled prevalence of stress.

Figure 4: Pooled prevalence of stress.

Findings from the qualitative review

Qualitative data were extracted from four studies. The data from three qualitative studies42–44 and one mixed-methods study45 were synthesized [Table 5].

The three included qualitative studies used different approaches to data analysis. Banerjee et al,44 used ‘Charmaz’s grounded theory approach’, followed ‘Colaizzi’s protocol’, and Chakma et al,42 did not use any preconceived theoretical framework but performed descriptive content data analyses. George et al,45 used the framework approach for data analysis. Thematic synthesis resulted in the following themes:

CHALLENGES

- Fear of contracting the disease and spreading it to family: a common theme in all four studies was fear of contracting the virus and spreading it to family members. Due to their daily contact with infected patients and the high infectivity of the novel virus, HCWs expressed fear of becoming infected themselves. They were also concerned about the possibility of transmitting the virus to their families, particularly vulnerable individuals such as children and elderly parents with chronic health conditions. Participants mentioned that severe infection and death were topics of conversation within their families.

- Extreme stress, anxiety, and frustration: all four studies also provided data on the high levels of stress experienced by HCWs. They expressed stress due to their high susceptibility to contracting the virus as well as the increased workload resulting from the high volume of patients, leading to exhaustion and frustration.42,45 One study highlighted that HCWs not only had the responsibility of providing care, but also the additional emotional burden of offering psychological and emotional counseling and assurance to patients, families, and colleagues.

- Work fatigue and disruption of everyday life: HCWs were expected to work for extended periods, to meet demand and cover staff illnesses. This resulted in significant fatigue and physical tension, impacting their mental health and decision-making abilities. The management’s ability to cope with the unprecedented pandemic situation exceeded their previous training and experience, resulting in overworking and excessive duty hours, leading to burnout. HCWs also faced challenges in balancing their work commitments with their family life, with separation from their families for extended periods being a significant disruption.

- Social stigma: findings from the qualitative study findings revealed that HCWs attending to COVID-19 patients experienced social discrimination and rejection. Neighbors, friends, and even family members treated them as potential spreaders of COVID-19, often influenced by media coverage. They faced unpleasant remarks and hesitancy from society to engage with them, leading to avoidance.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) concerns: HCWs expressed concerns about wearing PPE kits for prolonged periods, as it caused physical exhaustion, discomfort due to heat, and limited access to basic needs such as eating, drinking, and using the washroom easily. The quality of PPEs also was a cause of concern for the HCWs, undermining their confidence in providing care.

COPING STRATEGIES

- Family and peer support: HCWs expressed that the support they received from their immediate family, friends, and co-workers was crucial in helping them cope with the challenges they faced. Co-workers were a significant source of support, and sharing their difficult experiences with them was encouraging Having another family member on COVID-19 duty was a powerful motivator for HCWs. They also mentioned that appreciation from higher authorities and recognition on social media were uplifting for them.

- Self-care and lifestyle modifications: HCWs adopted individual coping strategies focused on self-care and making lifestyles modifications. They engaged in wellness activities and specific relaxation techniques such as yoga, meditation, listening to music, going for walks, and exercising to improve their physical and mental well-being.43

- Higher purpose through God/religion: for some HCWs, their faith in God and religious beliefs played a role in coping with the challenges they faced. Praying and spiritual dependency provided them with a sense of higher purpose and strength.42

- Value of duty and passion: many HCWs expressed that they felt a sense of duty and a calling to serve patients, even at the risk of their own lives. They recognized the value and strength of being healthcare professionals and believed that their passion for their work helped them cope.42,44

Synthesis of quantitative and qualitative findings

The quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated using the social determinants of health framework.47 The following domains were identified:

INDIVIDUAL DOMAIN

Fear of contracting and spreading COVID-19, as well as physical and emotional exhaustion, contributed to the significant stress and anxiety experienced by the HCWs. Individually, HCWs coped by engaging in self-initiated well-being activities, fulfilling moral and social obligations, and drawing strength from their own spiritual beliefs.

INTERPERSONAL (FAMILYAND PRESS)

HCWs with vulnerable family members, including the elderly and young children, were particularly concerned about their well-being. Some HCWs had to stay away from their families as a protective measure, which affected their mental health. Isolation and discrimination from family members and peers added to their stress. HCWs with childcare responsibilities faced difficulties in balancing home life and work. However, the support and encouragement from family and friends were crucial coping resources for HCWs.

HEALTH SERVIES DOMIN

Increased workload and long working hours were major sources of stress for HCWs. The lack of mental health support for the public and the support staff in healthcare settings placed emotion burdens on HCWs. Assuming new responsibilities without adequate preparation and working in unsafe environments with unpredictable consequences added to their anxiety and stress. PPE-related issues such as shortage, discomfort, and poor quality were additional stress factors.

COMMUNITY AND WIDER SOCITY

HCWs felt rejected and stigmatized by society, often facing discriminatory behaviors and hatred. Some faced eviction from rented properties, leading to depression. The support received from co-workers was highly valued by HCWs.

Discussion

India was one of the nations hardest-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. India’s dense population placed a massive burden on mortality and morbidity. The remarkable effect of COVID-19 had a grave psychological impact on the HCWs. Therefore, this mixed-methods review was undertaken to determine the impact of COVID-19 on HCWs’ mental health status in India and its attributing factors.

Compared to the global prevalence by Ghahramani et al,48 our review findings showed a lower prevalence of depression (32.96% vs. 36%) and anxiety (29.49% vs. 47%). Stress was the only exception, which had a higher prevalence in India (33.47% vs. 27%). According to our findings, the prevalence of depression and anxiety among HCWs is much higher in India than in the Asian subcontinent (China, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Jordan, Palestine, Turkey, India, and Pakistan) and the Southeast-Asia region (Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal) wherein the pooled prevalence was 27.2% (10 617/39 014), and 25.9% (6305/24 297) and 34.1% and 41.3%, respectively.49

The review also highlighted common themes identified in other studies worldwide,50 such as fear of contagion, issues with PPE, heavy workload, social stigma, and the complex dynamics between HCWs, family members, colleagues, media, and society. These findings demonstrate that the impact of COVID-19 on HCWs transcends geographical and temporal boundaries.

In India, PPE was a great concern for HCWs during the pandemic. Similarly, in Oman, they faced an excessive need for face masks and gowns which was tackled by the endowment fund dedicated to public healthcare services.51 Only one study included in the review compared the anxiety score between male and female HCWs which reported female HCWs had higher anxiety.25 This finding was similar to a study conducted among female HCWs during the pandemic in Oman wherein 27.9% had moderate to severe anxiety.52Another important stressor among the HCWs was the heavy workload which was causing fatigue and affecting their mental health due to the high number of cases admitted to the hospitals. An effective intervention to overcome such a challenge would be a healthcare system change. One of the exemplary models adopted in response to the pandemic in India was the Udupi-Manipal model which was a public-private partnership. One of the private hospitals was designated as a COVID-19 hospital to treat the overwhelming number of COVID-19 cases in the district.53 Similarly, the primary health care in Oman partnered with private establishments, in tracking, testing, managing the cases, and data management as well.54 However, studies on the role of the healthcare system in supporting the mental health of HCWs during the pandemic are lacking.

Recommendations for policy and practice

As HCWs continue to be the front-line workers in the face of the pandemic, they continue to be at significant risk of developing long-term psychological impacts. Implementing appropriate interventions to help HCWs cope with various mental health problems is the need of the hour. However, there were no studies on healthcare policies and interventional measures to meet the mental health needs of the HCWs during the pandemic. Due to the observed deficiency from this review, we recommend that there must be interventions and protocols at the institutional level, and policies at the governmental level to support HCWs’ mental health. Furthermore, adequate training in management and counseling services to equip the HCWs in providing care confidently can play a role in mitigating the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The role of media should be above and beyond to spread community awareness to remove the stigma associated with COVID-19.

Strengths and limitations

In our mixed method analysis, integrating the quantitative and qualitative data using the social determinants of health framework provided a comprehensive insight into the factors related to individuals, family, peers, community, health services, and wider society that influence the mental health of HCWs during the pandemic. There is no evidence of publication bias in the included studies in the three outcomes assessed.

Due to the I2 in the data from the included studies, we were unable to perform a sub-group analysis. Another limitation of this review was that outcomes like insomnia, fear, quality of life, psychological impact, and post-traumatic stress disorder were not measured because we found that the most reported mental health outcome among the HCWs in India was anxiety, stress, and depression.

Conclusion

This review emphasizes the significant prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among HCWs in India. Integrating quantitative and qualitative data explained the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of HCWs. We recommend multi-prong and multi-level approaches as a way forward to protect the HCWs and preserve their service.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. We acknowledge the funding agency Scheme for Promotion of Academic and Research Collaboration (SPARC), Department of Education, Govt. of India for supporting to collaborate with experts from UCL and the UCL-AIIMS collaboration grant.

references

- 1. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed 2020 Mar;91(1):157-160.

- 2. Aly HM, Nemr NA, Kishk RM, Elsaid NM. Stress, anxiety and depression among healthcare workers facing COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt: a cross-sectional online-based study. BMJ Open 2021 Apr;11(4):e045281.

- 3. Spilchuk V, Arrandale VH, Armstrong J. Potential risk factors associated with COVID-19 in health care workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2022 Jan;72(1):35-42.

- 4. Badahdah A, Khamis F, Al Mahyijari N, Al Balushi M, Al Hatmi H, Al Salmi I, et al. The mental health of health care workers in Oman during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2021 Feb;67(1):90-95.

- 5. Hossain MM, Rahman M, Trisha NF, Tasnim S, Nuzhath T, Hasan NT, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2021 Apr;7(4):e06677.

- 6. Pal R, Yadav U. COVID-19 pandemic in India: present scenario and a steep climb ahead. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:2150132720939402.

- 7. Verma S, Mishra A. Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020 Dec;66(8):756-762.

- 8. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang B, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. The Lancet Psychiatry 2020 Mar 1;7(3):e14.

- 9. Parthasarathy R, Ts J, K T, Murthy P. Mental health issues among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic - a study from India. Asian J Psychiatr 2021 Apr;58:102626.

- 10. Campbell R, Gregory KA, Patterson D, Bybee D. Integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches: an example of mixed methods research. In: Methodological approaches to community-based research. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. p. 51-68.

- 11. Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev 2017 Mar;6(1):61.

- 12. Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015 Sep;13(3):179-187.

- 13. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020.

- 14. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information 2018 Jan 1;34(4):285-291.

- 15. Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharyya R, Bhattacharyya S, Gupta S, Das S, Banerjee BB. Attitude, practice, behavior, and mental health impact of COVID-19 on doctors. Indian J Psychiatry 2020;62(3):257-265.

- 16. Wilson W, Raj JP, Rao S, Ghiya M, Nedungalaparambil NM, Mundra H, et al. Prevalence and predictors of stress, anxiety, and depression among healthcare workers managing COVID-19 pandemic in India: a nationwide observational study. Indian J Psychol Med 2020 Jul;42(4):353-358.

- 17. Dordi MD, Jethmalani K, Surendran KK, Contractor A. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Indian health care workers. Int J Indian psychol 2020 Aug;8(3):597-608.

- 18. Suryavanshi N, Kadam A, Dhumal G, Nimkar S, Mave V, Gupta A, et al. Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Brain Behav 2020 Nov;10(11):e01837.

- 19. Khanam A, Dar SA, Wani ZA, Shah NN, Haq I, Kousar S. Healthcare providers on the frontline: a quantitative investigation of the stress and recent onset psychological impact of delivering health care services during COVID-19 in Kashmir. Indian J Psychol Med 2020;42(4):359-367.

- 20. Chew NW, Lee GK, Tan BY, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020 Aug;88:559-565.

- 21. Rathore P, Kumar S, Choudhary N, Sarma R, Singh N, Haokip N, et al. Concerns of health-care professionals managing COVID patients under institutional isolation during COVID-19 pandemic in India: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Indian J Palliat Care 2020 Jun;26(Suppl 1): S90-S94.

- 22. Patel A, Kandre DD, Mehta P, Prajapati A, Patel B, Prajapati S. Multi-centric study of psychological disturbances among health care workers in tertiary care centers of Western India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neuropsychiatria i Neuropsychologia/Neuropsychiatry and Neuropsychology 2020;15(3):89-100.

- 23. Rehman U, Shahnawaz MG, Khan NH, Kharshiing KD, Khursheed M, Gupta K, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among Indians in times of covid-19 lockdown. Community Ment Health J 2021 Jan;57(1):42-48.

- 24. Uvais NA, Aziz F, Hafeeq B. COVID-19-related stigma and perceived stress among dialysis staff. J Nephrol 2020 Dec;33(6):1121-1122.

- 25. Gupta B, Sharma V, Kumar N, Mahajan A. Anxiety and sleep disturbances among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020 Dec;6(4):e24206.

- 26. Chauhan VS, Chatterjee K, Yadav AK, Srivastava K, Prakash J, Yadav P, et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 among health-care workers: an exposure-based cross-sectional study. Ind Psychiatry J 2021 Oct;30(3)(Suppl 1):S63-S68.

- 27. Das K, Ryali VS, Bhavyasree R, Sekhar CM. Postexposure psychological sequelae in frontline health workers to COVID-19 in Andhra Pradesh, India. Ind Psychiatry J 2021;30(1):123-130.

- 28. Dharra S, Kumar R. Promoting mental health of nurses during the coronavirus pandemic: will the rapid deployment of nurses’ training programs during COVID-19 improve self-efficacy and reduce anxiety? Cureus 2021 May;13(5):e15213.

- 29. Garg S, Yadav M, Chauhan A, Verma D, Bansal K. Prevalence of psychological morbidities and their influential variables among nurses in a designated COVID-19 tertiary care hospital in India: a cross-sectional study. Ind Psychiatry J 2020;29(2):237-244.

- 30. Khan H, Srivastava R, Tripathi N, Uraiya D, Singh A, Verma R. Level of anxiety and depression among health-care professionals amidst of coronavirus disease: a web-based survey from India. J Educ Health Promot 2021 Nov;10(1):408.

- 31. Jakhar J, Biswas PS, Kapoor M, Panghal A, Meena A, Fani H, et al. Comparative study of the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care professionals in India. Future Microbiol 2021 Nov;16:1267-1276.

- 32. Mishra S, Singh S, Tiwari V, Vanza B, Khare N, Bharadwaj P. Assessment of level of perceived stress and sources of stress among dental professionals before and during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2020 Nov;10(6):794-802.

- 33. Raj R, Koyalada S, Kumar A, Kumari S, Pani P, Nishant, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India: an observational study. J Family Med Prim Care 2020 Dec;9(12):5921-5926.

- 34. Chatterjee SS, Chakrabarty M, Banerjee D, Grover S, Chatterjee SS, Dan U. Stress, sleep and psychological impact in healthcare workers during the early phase of COVID-19 in India: a factor analysis. Front Psychol 2021 Feb;12:611314.

- 35. Sharma R, Saxena A, Magoon R, Jain MK. A cross-sectional analysis of prevalence and factors related to depression, anxiety, and stress in health care workers amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Anaesth 2020 Sep;64(Suppl 4):S242-S244.

- 36. Gupta AK, Mehra A, Niraula A, Kafle K, Deo SP, Singh B, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among the healthcare workers in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020 Dec;54:102260.

- 37. Singh J, Sood M, Chadda RK, Singh V, Kattula D. Mental health issues and coping among health care workers during COVID19 pandemic: Indian perspective. Asian J Psychiatr 2021 Jul;61:102685.

- 38. Sukumaran AB, Manju L, Jose R, Narendran M, Padmini C, Nazeema Beevi P, et al. Mental health problems among health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Community and Family Medicine. 2021 Jan;7(1):31-36.

- 39. Sharma SK, Mudgal SK, Thakur K, Parihar A, Chundawat DS, Joshi J. Anxiety, depression and quality of life (QOL) related to COVID-19 among frontline health care professionals: a multicentric cross-sectional survey. J Family Med Prim Care 2021 Mar;10(3):1383-1389.

- 40. Sharma V, Kumar N, Gupta B, Mahajan A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on orthopaedic surgeons in terms of anxiety, sleep outcomes and change in management practices: a cross-sectional study from India. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2021;29(1):23094990211001621.

- 41. Yadav R, Yadav P, Kumar SS, Kumar R. Assessment of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance in COVID-19 patients at tertiary care center of North India. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2021 Apr;12(2):316-322.

- 42. Chakma T, Thomas BE, Kohli S, Moral R, Menon GR, Periyasamy M, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India & their perceptions on the way forward - a qualitative study. Indian J Med Res 2021 May;153(5&6):637-648.

- 43. Golechha M, Bohra T, Patel M, Khetrapal S. Healthcare worker resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of primary care providers in India. World Med Health Policy 2022 Mar;14(1):6-18.

- 44. Banerjee D, Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Kallivayalil RA, Javed A. Psychosocial framework of resilience: navigating needs and adversities during the pandemic, a qualitative exploration in the Indian frontline physicians. Front Psychol 2021 Mar;12:622132.

- 45. George CE, Inbaraj LR, Rajukutty S, de Witte LP. Challenges, experience and coping of health professionals in delivering healthcare in an urban slum in India during the first 40 days of COVID-19 crisis: a mixed method study. BMJ Open 2020 Nov;10(11):e042171.

- 46. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008 Jul;8:45.

- 47. Patient Safety Learning - the hub. The Dahlgren-whitehead rainbow (1991). 2021 [cited 2023 January 16]. Available from: https://www.pslhub.org/learn/improving-patient-safety/health-inequalities/the-dahlgren-whitehead-rainbow-1991-r5870/.

- 48. Ghahramani S, Kasraei H, Hayati R, Tabrizi R, Marzaleh MA. Health care workers’ mental health in the face of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2023;27(2):208-217.

- 49. Thatrimontrichai A, Weber DJ, Apisarnthanarak A. Mental health among healthcare personnel during COVID-19 in Asia: a systematic review. J Formos Med Assoc 2021 Jun;120(6):1296-1304.

- 50. Billings J, Ching BC, Gkofa V, Greene T, Bloomfield M. Experiences of frontline healthcare workers and their views about support during COVID-19 and previous pandemics: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res 2021 Sep;21(1):923.

- 51. Al Fannah J, Al Harthy H, Al Salmi Q. COVID-19 pandemic: learning lessons and a vision for a better health system. Oman Med J 2020 Sep;35(5):e169.

- 52. Khamis F, Al Mahyijari N, Al Lawati F, Badahdah AM. The mental health of female physicians and nurses in Oman during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oman Med J 2020 Nov;35(6):e203.

- 53. Umakanth S. Udupi-Manipal model: public-private partnership during a public health emergency. 2020 [cited 2023 March 15]. Available from: https://www.pgurus.com/udupi-manipal-model-public-private-partnership-during-a-public-health-emergency/.

- 54. Al Ghafri T, Al Ajmi F, Al Balushi L, Kurup PM, Al Ghamari A, Al Balushi Z, et al. Responses to the pandemic COVID-19 in primary health care in Oman: Muscat experience. Oman Med J 2021 Jan;36(1):e216.