A 70-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a five-day history of diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and per rectal bleeding. Seven months previously, he was diagnosed with locally advanced esophageal carcinoma without metastasis. Ten days before this presentation, he underwent his second chemotherapy cycle containing docetaxel, 5-fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin. Figures 1–3 show coronal sections of the patient’s abdominal computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast.

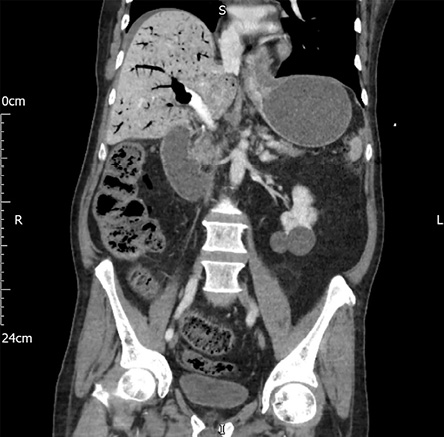

Figure 1: CT of the abdomen and pelvis

Figure 1: CT of the abdomen and pelvis

showing collections of air in the small and large intestines.

Figure 2: CT of the abdomen and pelvis showing hepatic-portol-venous gas, and air in the small and large intestines.

Figure 2: CT of the abdomen and pelvis showing hepatic-portol-venous gas, and air in the small and large intestines.

Figure 3: CT with intravenous contrast of the abdomen and pelvis showing hepatic-portol-venous gas and air in the small and large intestines.

Figure 3: CT with intravenous contrast of the abdomen and pelvis showing hepatic-portol-venous gas and air in the small and large intestines.

Questions

- What is this condition called?

- What are the causes of this condition?

- What is the possible cause for the present case?

Answers

- This condition is known as pneumatosis intestinalis (PI). Its radiological diagnosis is characterized by a cystic collection of air adjacent to the bowel’s lumen that runs parallel with the bowel wall or linear collections without air-contrast or air-fluid levels. Sometimes it is associated with hepatic-portol-venous

gas (HPVG).1

- The causes may be gastrointestinal, (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, ischaemic bowel disease, intestinal obstruction), non-gastrointestinal (e.g., medication-induced by chemotherapy or other immunosuppressive drugs), pulmonary diseases, iatrogenic (post endoscopy), or idiopathic.2

- The present case is likely to be chemotherapy-induced PI, as there is no pattern in the CT scans to suggest involvement of any vascular territory or large vessel occlusion in the mesentery.

Discussion

PI is a rare condition defined as the presence of extraluminal bowel gas confined within the bowel wall existing in any part of the gastrointestinal tract distal to the stomach. There are two types of PI; idiopathic or primary PI (15%) and secondary PI (85%), due to various gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal illnesses.2 The exact pathogenesis of PI is not fully understood and is proposed to be multifactorial.1,2 When seen in combination with HPVG, it is most frequently associated with bowel ischemia. However, HPVG can also be seen in PI due to other etiologies such as chemotherapy-induced PI.2,3

PI can be caused by several chemotherapeutic agents including 5-fluorouracil, docetaxel, and cisplatin. PI cases have also been reported due to molecular targeted therapy such as bevacizumab and sunitinib.2 The cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy on the intestinal epithelium can play a role in the pathogenesis of PI.2 Damage to the highly proliferated intestinal mucosa can occur rapidly during chemotherapy, and also, its interference with mucosal integrity can result in intramural air deposition. Depletion of submucosal lymphoid tissue or leukemic infiltrates; denuded Peyer’s patches producing mucosal defects after chemotherapy can also lead to gas entry into the bowel wall. Neutropenia also plays a vital role in the development of PI in patients receiving chemotherapy.2

The clinical symptoms vary from asymptomatic presentation to abdominal pain and distension, vomiting, diarrhea, and rectal blood loss.4 Radiological appearance of intramural gas confirms the diagnosis. Though management is generally conservative and includes nasogastric tube placement, bowel rest, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. A few patients (< 3%) who develop complications such as bowel perforation or bowel necrosis may require surgical intervention.3,5 Most patients recover in five days to one week. The recurrence of PI is not uncommon. Treating the underlying cause is the cornerstone of management of patients with PI.5

Disclosure

The patient's kin gave a written consent to use the patient's CT images or information for publication.

references

- 1. Khalil PN, Huber-Wagner S, Ladurner R, Kleespies A, Siebeck M, Mutschler W, et al. Natural history, clinical pattern, and surgical considerations of pneumatosis intestinalis. Eur J Med Res 2009 Jun;14(6):231-239.

- 2. Kouzu K, Tsujimoto H, Hiraki S, Takahata R, Yaguchi Y, Kumano I, et al. A case of pneumatosis intestinalis during neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for esophageal cancer. J Surg Case Rep 2017 Nov;2017(11):rjx227.

- 3. Mallappa S, Warren OJ, Kantor R, Mohsen Y, Harris S. Pneumatosis intestinalis and hepatic portal venous gas on computed tomography - a non-lethal outcome. JRSM Short Rep 2011 Nov;2(11):88.

- 4. Candelaria M, Bourlon-Cuellar R, Zubieta JL, Noel-Ettiene LM, Sánchez-Sánchez JM. Gastrointestinal pneumatosis after docetaxel chemotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002 Apr;34(4):444-445.

- 5. Zhang H, Jun SL, Brennan TV. Pneumatosis intestinalis: not always a surgical indication. Case Rep Surg 2012;2012:719713.