M etformin is a biguanide class hypoglycemic agent that is ubiquitous in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Metformin-induced lactic acidosis (MALA) has been widely recognized as a rare side effect, with an estimated incidence of 4.3 per 100 000 patient-years.1–3 These are described primarily in the setting of a drug overdose, acute on chronic metformin toxicity, end-stage renal disease, and acute compromise to renal perfusion in patients on chronic metformin therapy.2–4 The use of metformin in the pediatric population is limited, and that is described in the context of maturity-onset diabetes of the young.

There are few reports of MALA in the pediatric age group.5–8 However, none of these reports were in children taking therapeutic doses of metformin. We report a case of a three-year-old female receiving therapeutic metformin who developed MALA.

Case report

A three-year-old female with a history of complex congenital heart disease and previous cardiac surgeries was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in shock that progressed to cardiopulmonary arrest requiring resuscitation due to thrombosis in her right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery conduit. She subsequently demonstrated evidence of severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and acute kidney injury (AKI), of which the latter resolved.

The main reason for her subsequent PICU stay was for neurological rehabilitation and transition to home ventilation. She was receiving treatment for dystonia, heart failure, endocarditis, and pulmonary embolism. At the request of the parents, stem cell therapy for neurological dysfunction was investigated. As metformin has shown properties to recruit existing neural stem cells and enhance neural functions, a trial of therapy was initiated.9,10 The patient was placed on metformin (20 mg/kg) 17 days before the event, which was increased to 40 mg/kg (250 mg twice-daily) six days prior to the event.

On the day of the event, the patient acutely presented with a new wide complex bradycardia 70–80 beats per minute (bpm) from a baseline of 110–120 bpm and peaked T waves. The other vital signs were blood pressure = 90/40 mmHg, respiratory rate = 26 breaths per minute, temperature = 37.2 °C, and oxygen saturation = 87% on her baseline ventilation settings. She was poorly perfused with prolonged capillary refill time and lethargic. Immediate and subsequent venous blood sampling showed severe lactic acidosis and hyperkalemia [Table 1].

Table 1: Laboratory parameters prior to and after the event.

|

Serum pH |

7.19 |

7.03 |

6.96 |

7.20 |

7.36 |

7.38 |

7.30 |

7.31 |

7.35 |

|

pCO2 |

54 |

52 |

57 |

49 |

52 |

56 |

56 |

59 |

59 |

|

HCO3 |

20 |

13 |

12 |

18 |

29 |

32 |

27 |

29 |

32 |

|

Base excess |

-8 |

-17 |

-18 |

-9 |

+4 |

+7 |

+1 |

+2 |

+6 |

|

Lactate |

6.6 |

9.3 |

12.1 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

1.7 |

5.7 |

5.4 |

2.0 |

|

Potassium |

9.5 |

8.5 |

7.7 |

4.4 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

- |

5.5 |

2.9 |

|

Glucose |

8.7 |

13.5 |

24.7 |

12.9 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

- |

7.6 |

3.9 |

|

Blood urea nitrogen |

15.4 |

14.1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

13.4 |

- |

- |

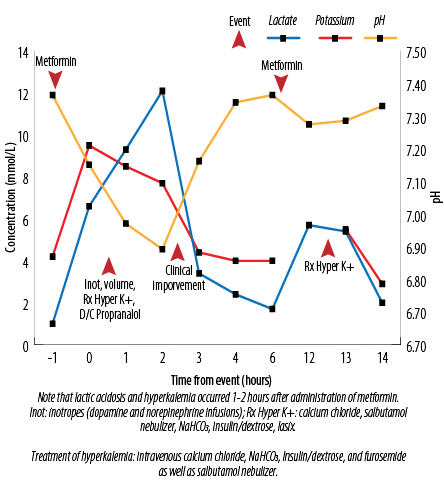

Figure 1: The biochemical relationship of administration of metformin with hyperkalemia and the treatments administered.

She was managed for hyperkalemia, and propranolol was discontinued. She became hypotensive, requiring dopamine and norepinephrine infusions, and higher ventilator support. The patient’s clinical status improved within three hours, and support therapies were weaned towards the baseline. Twelve hours after the initial event, a similar episode recurred with a rise in serum lactate and hyperkalemia, which was treated similarly and resolved. A detailed review of both events demonstrated that they occurred 1 to 2 hours after the administration of metformin. In addition, her creatinine levels had doubled five days prior to the event with a recent increment in metformin dose six days before.

At this point, metformin was discontinued. No further episodes were noted, and her clinical status returned to baseline [Figure 1].

Discussion

Multiple case series and reports have documented the rare but severe side effect of MALA.1,3 Although a 2010 Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence from prospective comparative trials or observational cohort studies that metformin is associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis, such methodologies are often insufficient for documentation of rare side effects. This is even rarer in patients receiving therapeutic doses of metformin.11 There are very few reported cases of MALA in the pediatric age group.5,7,8

A multicenter case series of American poison control centers evaluated 37 children. The absolute doses ingested ranged from 250 mg to 16.5 g (mean = 1.7 g). None of these children experienced hypoglycemia. Of the 22 children who had blood work done, none had hyperlactatemia, acidosis, or electrolyte imbalances.7

There are three reports of attempted suicides in adolescents who developed MALA and AKI.5,8,12 All received treatments for hyperkalemia and hemodialysis, leading to full recovery. The case we present is the youngest case of reported MALA in a patient receiving therapeutic doses of metformin.

Patients with metformin toxicity are reported to have nausea, emesis, hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia, lethargy, abdominal pain, hypothermia, respiratory failure, hypotension, and cardiac dysrhythmias.13,14

Our patient was lethargic, hyperglycemic, and hypotensive with increased ventilator requirements. She also presented with cardiac dysrhythmia, likely secondary to the hyperkalemia that resulted from acidosis. The mortality rate is reported at 50%.15

Metformin has an affinity for the mitochondrion membrane. Due to this affinity, metformin affects electron transport and thereby inhibits oxidative metabolism. Especially when metformin levels are high, oxidative phosphorylation is reduced, and aerobic metabolism switches to anaerobic. Metformin can also delay or decrease gastrointestinal glucose absorption, hepatic gluconeogenesis from pyruvate lactate and alanine, and increase intestinal lactate production and peripheral insulin-related glucose reuptake.2,12,16,17

There is no direct mechanism described of metformin toxicity causing hyperkalemia. It has been proposed that MALA should no longer be considered as a single entity since many pathological mechanisms may trigger and sustain hyperlactatemia, including hypoxia.2,4 In our patient, the presence of AKI leading to hyperkalemia and subsequent dysrhythmias may have played a role in worsening her hemodynamic status leading to a further increase in serum lactate (type A lactic acidosis).

MALA may occur in chronic therapeutic dosing when an acute event affects a patient’s ability to excrete metformin. Such events include renal insufficiency, dehydration, dosage increase, sepsis, shock, or acidosis.17 Our described case was noted

to have rising creatinine about a week prior, as well as an increase in her metformin dose. She was on diuretics and so may have had an element of intravascular depletion.

Metformin is absorbed through the small intestine, is concentrated in enterocytes and hepatocytes and peaks at one to two hours, circulates essentially unbound, and has renal elimination in 12 hours. Its plasma half-life is 1.5–4.9 hours.4,17,18 This supports the association of metformin intake and the timing of the occurrence of biochemical changes in the described patient.

A limitation of our study is that metformin levels were not collected. However, the constellation of biochemical findings and its association with the timing of drug delivery was suggestive of a cause and effect relationship. The patient was not receiving any other medications at or close to the time of metformin administration. Other diagnoses that we looked into included sepsis and rhabdomyolysis. However, she recovered rapidly with the treatment administered, and her creatinine kinase levels were normal, and blood cultures sterile despite the absence of new anti-infective agents.

Conclusion

MALA is an entity seen in the pediatric age group using therapeutic doses of metformin. Prescribing practitioners should be aware of this rare yet serious side effect and prescribe it with caution in the setting of renal impairment. In cases of unexplained lactic acidosis, especially in the setting of renal impairment in a patient receiving metformin, one should suspect MALA and test metformin levels as well as discontinue the drug.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1. Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 Apr;(4):CD002967.

- 2. Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2014 Dec;312(24):2668-2675.

- 3. Misbin RI, Green L, Stadel BV, Gueriguian JL, Gubbi A, Fleming GA. Lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes treated with metformin. N Engl J Med 1998 Jan;338(4):265-266.

- 4. Arieff AI. Pathogenesis of lactic acidosis. Diabetes Metab Rev 1989 Dec;5(8):637-649.

- 5. Gura M, Devrim S, Sagiroglu A, Orhon Z, Sen B. Severe metformin intoxication with lactic acidosis in an adolescent: a case report. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology 2009;27.

- 6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, McMillan N, Ford M. 2013 annual report of the American association of poison control centers’ national poison data system (NPDS): 31st annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014 Dec;52(10):1032-1283.

- 7. Spiller HA, Weber JA, Winter ML, Klein-Schwartz W, Hofman M, Gorman SE, et al. Multicenter case series of pediatric metformin ingestion. Ann Pharmacother 2000 Dec;34(12):1385-1388.

- 8. Lacher M, Hermanns-Clausen M, Haeffner K, Brandis M, Pohl M. Severe metformin intoxication with lactic acidosis in an adolescent. Eur J Pediatr 2005 Jun;164(6):362-365.

- 9. Menendez JA, Vazquez-Martin A. Rejuvenating regeneration: metformin activates endogenous adult stem cells. Cell Cycle 2012 Oct;11(19):3521-3522.

- 10. Wang J, Gallagher D, DeVito LM, Cancino GI, Tsui D, He L, et al. Metformin activates an atypical PKC-CBP pathway to promote neurogenesis and enhance spatial memory formation. Cell Stem Cell 2012 Jul;11(1):23-35.

- 11. Lalau JD, Mourlhon C, Bergeret A, Lacroix C. Consequences of metformin intoxication. Diabetes Care 1998 Nov;21(11):2036-2037.

- 12. Al-Abri SA, Hayashi S, Thoren KL, Olson KR. Metformin overdose-induced hypoglycemia in the absence of other antidiabetic drugs. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013 Jun;51(5):444-447.

- 13. Pearlman BL, Fenves AZ, Emmett M. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis. Am J Med 1996 Jul;101(1):109-110.

- 14. Heaney D, Majid A, Junor B. Bicarbonate haemodialysis as a treatment of metformin overdose. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997 May;12(5):1046-1047.

- 15. Lalau JD, Race JM. Metformin and lactic acidosis in diabetic humans. Diabetes Obes Metab 2000 Jun;2(3):131-137.

- 16. Bruijstens LA, van Luin M, Buscher-Jungerhans PM, Bosch FH. Reality of severe metformin-induced lactic acidosis in the absence of chronic renal impairment. Neth J Med 2008 May;66(5):185-190.

- 17. Kopec KT, Kowalski MJ. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA): case files of the Einstein Medical Center medical toxicology fellowship. J Med Toxicol 2013 Mar;9(1):61-66.

- 18. Sánchez-Infantes D, Díaz M, López-Bermejo A, Marcos MV, de Zegher F, Ibáñez L. Pharmacokinetics of metformin in girls aged 9 years. Clin Pharmacokinet 2011 Nov;50(11):735-738.