P eripherally inserted central catheterization (PICC) insertion is routinely performed in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for providing nutritional and medical support for preterm and critically ill newborns. Among the methods to achieve central vascular access, PICC carries fewer complications, and the line tends to remain functional for longer periods. Crucial for the first puncture success is finding a good vein. This can be challenging in chronically ill preterm neonates, having already undergone multiple insertion attempts during their prolonged hospital stay. In this report, we describe our successful experience of neonatal PICC line insertion through an unusual site, using superficial abdominal veins as initial access.

Case Report

A preterm baby boy weighing 1800 g was born at 30 weeks of gestation. He went through a stormy course perinatally and as a neonate. At the time of our procedure, his corrected age was two months and weight was 3 kg. The baby had been diagnosed with necrotizing enterocolitis thrice during his postnatal period. He had multiple episodes of culture-proven sepsis in addition to persistent candidemia requiring antibiotic and antifungal treatment. He had been operated on several times which were complicated by anastomotic leak and strictures, requiring exploratory laparotomy. In addition, he developed a gangrenous left arm attributed to iatrogenic arterial cannulation and underwent autoamputation. He also had chronic lung disease and remained on chronic non-invasive ventilation. He was born with a metabolic bone disorder complicated by a fractured right humerus. He also had developed conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, possibly due to chronic total preantral nutrition (TPN) use which possibly led to cholestasis and jaundice. Furthermore, the baby developed cystic periventricular leukomalacia related to grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage and retinopathy of prematurity.

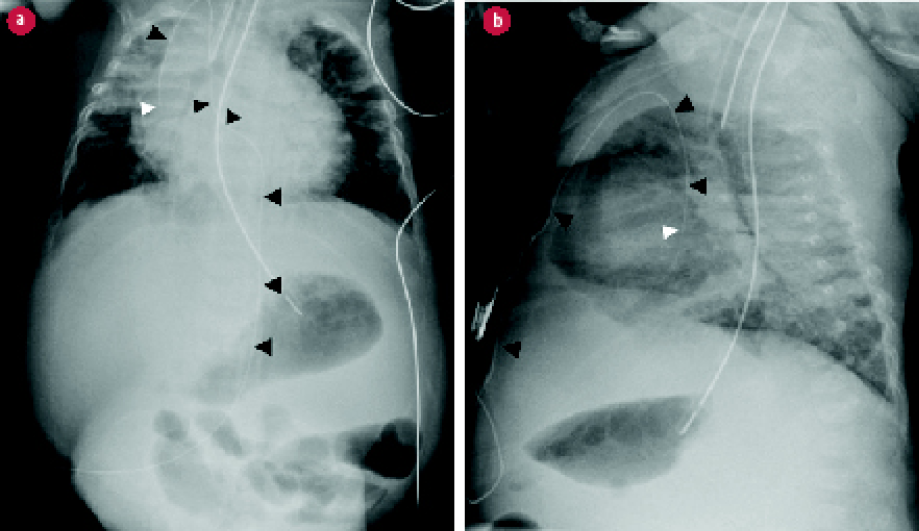

Figure 1: Abdominal and chest radiographs post insertion of the peripherally inserted central catheterization (PICC) catheter. (a) Frontal and (b) lateral views show the course of the inserted PICC from the anterior abdominal wall above the umbilicus to the right chest wall (black arrowheads). Its tip is at the cavoatrial junction in both frontal and lateral views (white arrowheads).

Figure 1: Abdominal and chest radiographs post insertion of the peripherally inserted central catheterization (PICC) catheter. (a) Frontal and (b) lateral views show the course of the inserted PICC from the anterior abdominal wall above the umbilicus to the right chest wall (black arrowheads). Its tip is at the cavoatrial junction in both frontal and lateral views (white arrowheads).

With such complications and procedures, the baby had been subjected to multiple venous accesses. Several central and peripheral lines, multiple PICC lines, and central venous catheters had used up almost all the commonly known accesses. Both internal jugular veins had been used for central lines on different occasions inserted in the operation room by pediatric surgeons and anesthesia teams, resulting in complete occlusion. Most veins in the upper limbs (basilic, cephalic, axillary, and brachial veins) and lower limbs (greater and lesser saphenous and popliteal veins) were already used. Bilateral scalp veins were used for PICC lines. The small veins in the hands and feet were also mostly punctured.

As a new PICC line was imperative for the continuation of care, we attempted inserting one from an unusual access point—a superficial vein in the anterior abdominal wall—and successfully accomplished it. To our knowledge, the literature has not reported a similar procedure.

Under complete aseptic technique, a 1Fr size PICC (1 Fr PICC) was used to access one of the superficial veins in the midline of the anterior abdominal wall in epigastrium coursing slightly deeper, probably into the superior or inferior epigastric veins, then to the internal mammary vein (internal thoracic vein), and finally into the superior vena cava (SVC). Chest X-ray post PICC insertion showed the catheter tip at the junction between the right atrium and SVC, exactly where it should be. There was good backflow from the catheter and its position was confirmed radiologically by abdominal and chest radiographs as reviewed by the interventional radiologist [Figure 1]. Thereafter, the catheter was used effectively

to continue the baby’s treatment.

Discussion

Inserting PICC in chronically ill, low birthweight preterm neonates can be challenging. During their prolonged hospital stay, multiple venipuncture attempts are made for the continuation of treatment. Several attempts are usually needed before a successful access to the preterm neonate’s extremely delicate veins, leaving progressively fewer viable venous sites for additional trials. The one-puncture success rate in very low birthweight and critically ill neonates has been estimated to be 77.8% with an overall total puncture success rate of 99.7%.1

In our case is a level III NICU with about 40 beds connected to the cardiac center. The unit uses high-frequency oscillatory ventilation and inhaled nitric oxide. Our guideline is to resuscitate newborns of ≤ 23 weeks of gestation and weighing ≤ 550 g. Borderline cases are evaluated by the senior consultant in the team and decision is made on a case-to-case basis.

The present patient required a new PICC line to deliver medications, fluids, and TPN. Normally, a PICC line is inserted through the arms (basilic, cephalic, brachial, and axillary veins), legs (greater and lesser saphenous and popliteal veins), or the scalp (temporal and posterior auricular veins).2,3 As these sites were already consumed in this baby, it was decided to try from an unusual location—the visible veins on the abdominal wall.

The procedure was performed by a skilled neonatologist experienced in difficult PICC insertions, helped by a pediatric specialist and an experienced NICU PICC nurse. The infection control team ensured a complete antiseptic environment before and during the procedure. A 1Fr PICC was inserted in the classical way using an introducer. The catheter’s unusual course passed from the midline of the anterior abdominal wall superiorly. We believe that the catheter passed through an internal thoracic vein that drains into SVC. We do not usually perform real-time ultrasonography to monitor the PICC tip position. Adequate backflow from the catheter was the first indication that the PICC tip had successfully reached the target location. The correct positioning of the tip at the junction of SVC and right atrium was subsequently confirmed by two X-rays [Figure 1], as validated by the interventional radiologist.

The placement of the PICC tip is a sensitive task. Experts caution that the catheter tip must stay outside the cardiac silhouette to avoid injury to endocardium and epicardium while being sufficiently near the heart to maintain the line’s central character. One study reported that non-central lines might generate eight-fold more complications than central lines.4 When inserting the PICC line from upper extremities, it is advised to keep the tip in the inferior third of the SVC. For lower limb insertion, it is advised to keep the tip of the PICC line in the inferior vena cava at the level above L4/L5 vertebral bodies or above the iliac crest line, but well outside the heart.5 Another suggestion is to keep PICC line tip 1 cm away from the heart in preterm babies, and 2 cm away in term babies.6

Neonatal PICC lines are prone to complications. A large retrospective study involving 2574 PICC insertions in 1807 children reported complications in 20.8% of the lines.7 The most common ones were accidental dislodgement (4.6%), infection (4.3%), occlusion (3.7%), local infiltration (3.0%), leakage (1.5%), breakage (1.4%), phlebitis (1.2%), and thrombosis (0.5%). Rare complications included cardiac arrythmia, pericardial effusion, and pericardial tamponade.

In the present case, our unusual line remained free of significant complications. We used it successfully for almost 20 days for interventional medication and TPN. Low dose heparin infusion helped maintain the line patency.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the viability of an unusual site for a neonatal PICC insertion, the first in the literature to our knowledge. The catheter coursed from superficial abdominal veins to epigastric vein, to internal thoracic vein, and internal jugular vein to reach the SVC near the right atrium. The catheter tip position was confirmed by backflow and X-rays before using the line. The catheter was used safely and effectively for almost 20 days to deliver medications, fluids, and TPN to the patient. The integrity of the PICC line was verified daily to avoid associated complications.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Written consent was obtained from the patient.

references

- 1. Li R, Cao X, Shi T, Xiong L. Application of peripherally inserted central catheters in critically ill newborns experience from a neonatal intensive care unit. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019 Aug;98(32):e15837.

- 2. Hayatghib FD, Cole P, Lee HC. Peripherally inserted central catheter in a neonate. Neoreviews 2008 Jun;9(6):e271-e273.

- 3. Pettit J. Assessment of infants with peripherally inserted central catheters: part 1. Detecting the most frequently occurring complications. Adv Neonatal Care 2002 Dec;2(6):304-315.

- 4. Racadio JM, Doellman DA, Johnson ND, Bean JA, Jacobs BR. Pediatric peripherally inserted central catheters: complication rates related to catheter tip location. Pediatrics 2001 Feb;107(2):E28.

- 5. Chock Valerie Y. Therapeutic techniques: peripherally inserted central catheters in neonates. Neoreviews 2004 Feb;5(2):e60-e62.

- 6. Nowlen TT, Rosenthal GL, Johnson GL, Tom DJ, Vargo TA. Pericardial effusion and tamponade in infants with central catheters. Pediatrics 2002 Jul;110(1 Pt 1):137-142.

- 7. Jumani K, Advani S, Reich NG, Gosey L, Milstone AM. Risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter complications in children. JAMA Pediatr 2013 May;167(5):429-435.