A glomus tumor is a mesenchymal tumor composed of modified smooth muscle cells representing a neoplastic counterpart of the perivascular glomus bodies. Although the usual location of glomus tumor is either the dermis or subcutis of the extremities, it can also occur infrequently in internal organs such as the mediastinum, lung, trachea, stomach, renal pelvis, cecum, and ovary.1–3 Gastric glomus tumors are rare and mostly benign. Malignant variants of glomus tumors account for 1% of all glomus tumor cases.4 Here we report one such rare case of malignant glomus tumor of the stomach in an adult female patient.

Case Report

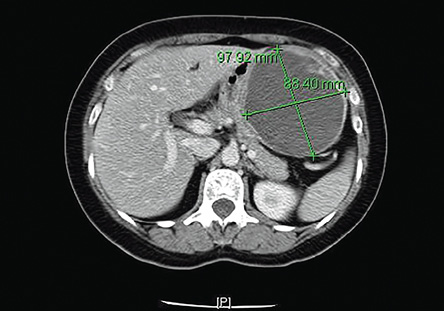

Figure 1: Computed tomography scan of the abdomen showing a well-defined cystic mass in the subdiaphragmatic region in close contact with the lateral wall of the stomach, and with thick internal septations.

Figure 2: Gross cut section of the mass attached to the wall of the stomach. The mass was multicystic and measured 10 × 9 × 7.5 cm.

A 53-year-old female was admitted to King Khalid University Hospital with a four-month history of fullness and pain in the left hypochondrium, which was aggravated by meals and deep breathing. She had a history of anorexia and weight loss. Her laboratory investigations were all within normal range. A gastrofibroscopy test revealed a well-circumscribed elevated lesion located in the gastric fundus. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen demonstrated a large, well-defined, cystic lesion, measuring 97 × 88 × 11 mm in close relation to the left lateral wall of the stomach. The lesion had a thick enhancing wall with thick peripheral internal septations [Figure 1]. The patient underwent laparotomy and resection of the gastric mass.

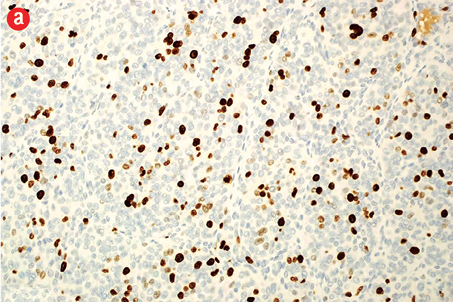

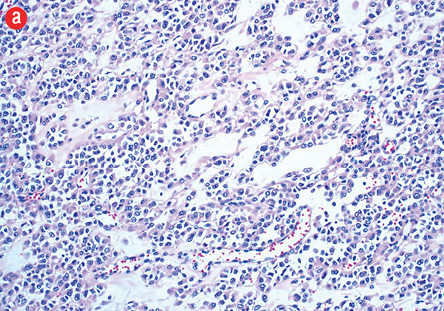

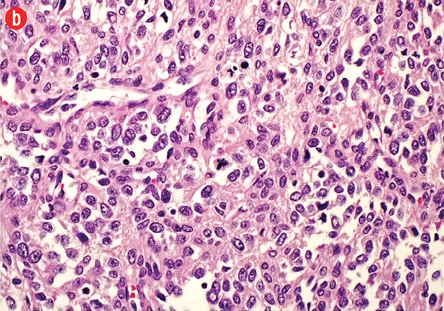

Grossly, the tumor measured 10 cm in maximum dimension, was cystic and had a smooth outer surface and was attached to part of the stomach. The cut section was multicystic and filled with hemorrhagic fluid [Figure 2]. Microscopically, the tumor showed submucosal infiltration by solid sheets of round cells having a nodular pattern of growth, separated by streaks of smooth muscle and fibrous bands. The neoplastic cells were uniform with round nucleus, clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a distinct cell border separated by a dilated vascular channel lined with flat endothelium [Figure 3a]. Also, there were areas showing increased cellularity, nuclear atypia, nuclear overlapping, and cuffing of vascular channels by these atypical cells [Figure 3b]. The mitotic count in these areas was approximately 10/50 high-power field (HPF) with the presence of atypical mitosis. There were areas of necrosis. The proliferative index (Ki-67) in cellular areas was 15% [Figure 4a].

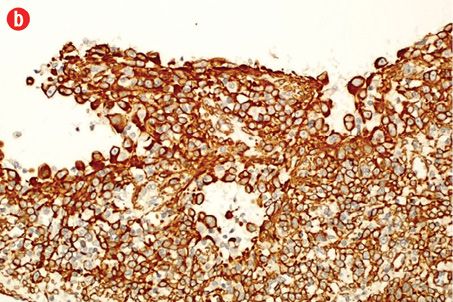

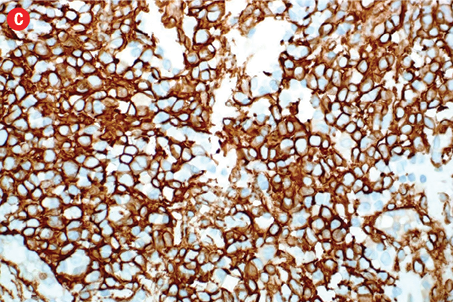

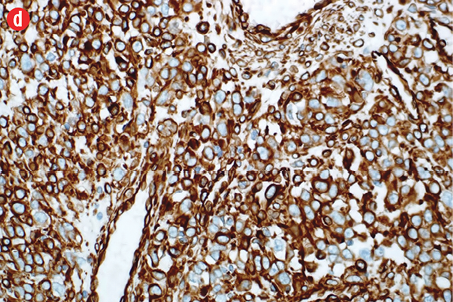

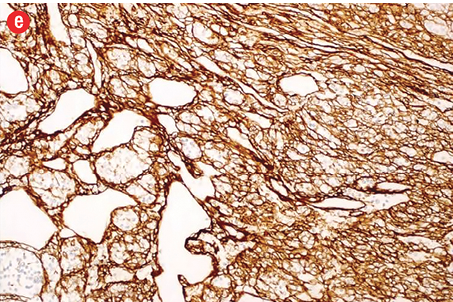

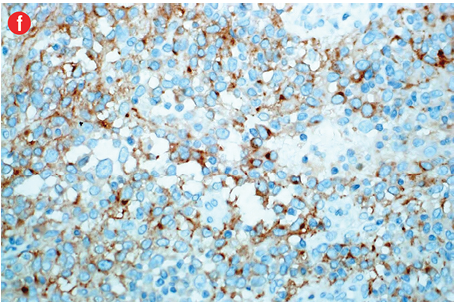

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were stained positive for alpha smooth muscle actin [Figure 4b], h-caldesmon [Figure 4c], vimentin [Figure 4d], pericellular net-like positivity for collagen type IV [Figure 4e], and focal perinuclear dot-like positivity for synaptophysin [Figure 4f]. The tumor cells were negative for CD117, CD34, cytokeratin, HMB-45, S-100, desmin, and chromogranin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4: (a) Proliferative index (Ki-67) is approximately 15% in the cellular areas, magnification = 200 ×. Cells stained positively for (b) alpha smooth muscle actin, (c) h-caldesmon, (d) vimentin, (e) collagen type IV, and (f) synaptophysin. Magnification of b, c, d, f = 400 ×. Magnification of e = 200 ×. |

The patient continues regular follow-up, and there was no evidence of recurrence 15 months after the resection of her gastric mass.

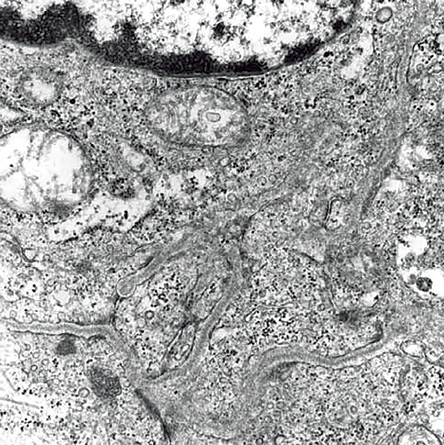

Figure 5: Electron microscopy showing tumor cells invaded by dense basal lamina and perinuclear myofilaments. Magnification = 12,000 ×.

Discussion

A visceral glomus tumor is a rare entity and may be discovered in the stomach, precoccygeal soft tissue, bone, nerve, lung, and mediastinum, with the stomach being most frequently involved.2 Gastric glomus tumors share similar histopathological features as the peripheral counterpart. However, the visceral glomus tumor usually does not show any clinical symptoms because of the relative larger space for the growth of the tumors, especially in the early stages, compared to the narrow tissue space for the glomus tumor in the extremities.5

Although most glomus tumors are characteristically benign and are not known to metastasize, there are rare examples of glomus tumors appearing malignant based on histological features such as nuclear atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity. Criteria have been suggested by Folpe et al,4 for defining malignancy in glomus tumors and estimating the risk of recurrence and metastasis. These include deep location, size >20 mm, atypical mitotic figures, the combination of moderate to high nuclear grade, and mitotic activity of more than five mitoses per 50 (HPF).

The authors of a study conducted in 2002 noted a much more favorable prognosis for internal malignant glomus tumors compared to those found at the deep peripheral sites.2 Therefore, they suggested that the criterion ‘deep location’ does not apply to these gastric glomus tumors with bad prognosis and, consequently, should not be used in the same way as for peripheral tumors. Additionally, they concluded that a size of 5 cm is a more appropriate indicator of malignancy because a gastric glomus tumor of that size has a higher potential for metastasis.

Immunohistochemically, glomus tumors of all types (benign and malignant) are positive for alpha smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, vimentin, and collagen IV, and show focal dot-like positivity with synaptophysin. They are negative for CD34, CD117, S100, and cytokines.6–9

Gastrointestinal glomus tumors are histologically and immunophenotypically entirely comparable with the tumors of peripheral soft tissues except focal perinuclear dot-like positivity for synaptophysin, which is commonly seen in gastric glomus tumors.2 To date, only nine cases of malignant glomus tumors of the stomach have been reported in the English-language literature [Table 1].2,4,7,10–14 All these tumors fulfilled the histological criteria proposed by Folpe et al,4 for a malignant glomus tumor. Of these nine cases of malignant gastric glomus tumors, six cases have been documented to metastasize to the liver, brain, kidney, and skin.

Figure 3: (a) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Branching vascular channels separated by stroma containing glomus cells in nests, aggregates. The tumor cells are uniform, round, sharply demarcated, with distinct cell borders, arranged around prominent, dilated vascular channels, magnification = 200 ×. (b) Areas showing overall maintenance of architecture, but with malignant appearing round cells showing increased cellularity, pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and atypical mitosis, magnification = 400 ×.

Glomus tumor should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses when a patient presents with a gastric lesion. Even though the majority of gastric glomus tumors are considered benign, the possibility of a malignant glomus tumor, although very rare, should not be overlooked. Careful histological examination of the excised lesion is fundamental for determining the definitive diagnosis. Wide surgical resection is usually curative and remains the mainstay of treatment. Careful long-term follow-up is recommended as the tumor may recur locally or may even rarely metastasize distally.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.