One of the commonest ailments in pregnancy is nausea and vomiting, affecting up to 80% cases.1,2 Its severe form, found in around 3% cases, is hyperemesis gravidarum (HG), the leading cause for hospitalization in the first half of pregnancy.2,3 HG can cause maternal weight loss, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies, and peripheral neuropathy.2 A rare complication associated with HG is Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), characterized by a triad of acute-onset encephalopathy, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia.4,5,6 WE is encountered in severe thiamine-deficient states associated with chronic alcoholism, prolonged parenteral nutrition, gastrointestinal carcinoma, eating disorders, chronic diarrhoea, and persistent vomiting.7 Sheehan in 1939 first described the relation between HG and WE.8 HG leading to WE may trigger serious maternal and fetal complications. This case report describes our clinical encounter with this rare phenomenon.

Case report

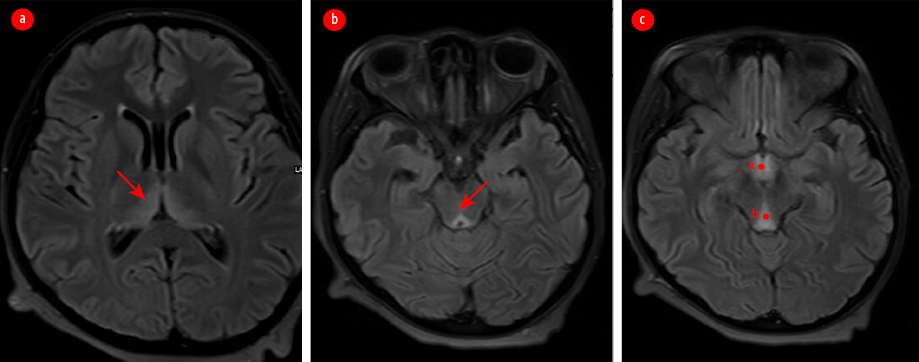

A 24-year-old primigravida at 12 weeks of gestation presented to the emergency room with weakness, mental confusion, and visual disturbance. On examination, her pulse was 100 beats per minute and blood pressure 100/60 mm Hg. She appeared disoriented and had nystagmus, photoreactive pupils, and preserved visual acuity. She had an atypical gait with a history of occasional falls. She revealed that she experienced excessive nausea and vomiting since her conception and had been hospitalized thrice to manage episodes of hyperemesis gravidarum. Blood investigations revealed hemoglobin = 11 gm/dL, potassium = 2.8 mmol, sodium = 133 mmol, blood glucose = 60 mg/dL, and normal renal, liver, and thyroid functions. Urine analysis showed ketonuria. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia while ultrasound showed a single live intrauterine fetus of 12 weeks of gestation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain reported bilateral symmetrical altered signal intensities in the medial and posterior aspects of both thalami, periaqueductal grey matter, and tectal plate, suggesting WE [Figure 1].

Figure 1: MRI of the brain showing symmetrically altered intensities of signals in the (a) medial and posterior aspects of both thalami, (b) periaqueductal grey matter, and (c) tectal plate.

Figure 1: MRI of the brain showing symmetrically altered intensities of signals in the (a) medial and posterior aspects of both thalami, (b) periaqueductal grey matter, and (c) tectal plate.

The patient was admitted and treated by a multidisciplinary team of obstetricians, neurologists, an intensivist, and an ophthalmologist. She was administered normal saline along with potassium replacement. She was also given thiamine 500 mg intravenous loading dose every eight hours for three days, and then maintained with 100 mg orally for another 14 days. The patient showed slow improvement in her neurological condition and was discharged after two weeks of hospitalization. On follow-up within three months of initiation of the treatment, her ophthalmologic condition and the fetal growth were found to be normal. Throughout her pregnancy, she continued taking the oral thiamine supplementation (100 mg thrice daily). Her gait, however, continued to be atypical till delivery.

The patient underwent caesarean section at 39 weeks and 2 days because of contracted pelvis: per-vaginal examination revealed that the sacral promontory could be palpated, the pelvic sidewalls were convergent with small inter-ischial diameter and narrow subpubic angle. She delivered a healthy 2.8 kg baby. After an uneventful postpartum period, she was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Discussion

WE is more common in alcoholics, but do occur very rarely in non-alcoholics (0.04–0.13%).9 WE can also be found in cases of anorexia nervosa, chemotherapy-induced vomiting, gastrointestinal disease, hemodialysis, and HG.4 The main reason behind WE is the deficiency of thiamine, whose active form called thiamine pyrophosphate, acts as a coenzyme in many biochemical pathways in the brain.10 In the thiamine-deficient state, the transketolase, alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and pyruvate dehydrogenase pathways in the brain are disrupted, leading to neuronal damage.10 In practice, WE can be diagnosed by Caine’s operational criteria since not all patients manifest the classical triad of encephalopathy, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia. Caine’s working criteria for WE comprise the clinical symptom-triad, clinical response to thiamine, and autopsy evidence of WE.11 The defining signs and symptoms according to Caine’s criteria are dietary deficiencies, oculomotor changes (nystagmus or ophthalmoplegia), cerebellar dysfunction (falling or imbalance), and altered mental state (delirium, confusion, cognitive disturbances).11

The daily requirement of thiamine for normal females is 1.1 mg/day, which increases to 1.5 mg/day during pregnancy and lactation.12 The requirement is further escalated in cases of HG, where absorption is reduced. Determination of blood transketolase activity and thiamine pyrophosphate reflects the thiamine status in the body.13

If the correction of fluid imbalance in HG is done with dextrose without thiamine supplementation, WE can be precipitated. A recent systematic review of WE in pregnancy revealed a maternal mortality rate of 5%, and fetal mortality rate of 50% despite diagnosis and treatment.5 WE has also been associated with permanent neurologic damage and Korsakoff syndrome. Korsakoff syndrome is characterized by marked irreversible deficiency of antegrade and retrograde memory and can be fatal in 10–20% of cases.9 The fetal complications associated with WE are miscarriage, preterm birth, intrauterine growth retardation, and intrauterine fetal death in case of severe maternal compromise.9 The typical findings in MRI are symmetrical hyperdense lesions in the thalamus, mammillary bodies, tectal plate, and periaqueductal area.13 The diagnosis of WE is based on the clinical findings and rapid reversal of symptoms with thiamine.

Our patient had the classical triad of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and encephalopathy with HG, and corroborative MRI images. Due to clinical severity, it was decided to treat her with a high thiamine dose of 500 mg intravenously thrice daily for three days, followed by 100 mg thrice daily throughout pregnancy. This regimen was advised by the neurologists based on their clinical experience, and no adverse effects of thiamine were noted. Currently, there are no universally accepted guidelines for the optimal duration, route, or dose of thiamine.14 The Royal College of Physicians recommends an initial dose of intravenous (IV) thiamine 500 mg thrice daily for three days and IV 250 mg daily for the next 3–5 days, followed by oral 100 mg for the rest of the hospital stay and outpatient treatment.15 The European Federation of Neurological Societies suggests IV thiamine 200 mg thrice daily before carbohydrate intake, to be continued until there is no further improvement in signs and symptoms.16 In their review of 49 cases, Chiossi et al,12 concluded that resolution of symptoms required months, and complete remission occurred only in 28% of cases, spontaneous fetal loss occurred in 37%, and elective abortion was performed in 10% of cases. Although WE due to HG is rare, clinicians must be aware of it and provide prompt management.

Conclusion

WE associated with hyperemesis is a rare life-threatening condition. This case report highlights the importance of multidisciplinary management with thiamine supplementation for a favorable maternal and fetal outcome in pregnant women.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

references

- Niebyl JR. Clinical practice. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2010 Oct;363(16):1544-1550.

- 2. Boelig RC, Barton SJ, Saccone G, Kelly AJ, Edwards SJ, Berghella V. Interventions for treating hyperemesis gravidarum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 May;2016(5):CD010607.

- 3. Jarvis S, Nelson-Piercy C. Management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. BMJ 2011 Jun;342:d3606.

- 4. Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Jamieson DJ, Schild L, Adams MM, Deshpande AD, et al. Hospitalizations during pregnancy among managed care enrollees. Obstet Gynecol 2002 Jul;100(1):94-100.

- 5. Oudman E, Wijnia JW, Oey M, van Dam M, Painter RC, Postma A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy in hyperemesis gravidarum: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019 May;236:84-93.

- 6. Olmsted A, DeSimone A, Lopez-Pastrana J, Becker M. Fetal demise and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in a patient with hyperemesis gravidarum: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2023 Feb;17(1):32.

- 7. Sulaiman W, Othman A, Mohamad M, Salleh HR, Mushahar L. Wernicke’s encephalopathy associated with hyperemesis gravidarum - a case report. Malays J Med Sci 2002 Jul;9(2):43-46.

- 8. Ashraf VV, Prijesh J, Praveenkumar R, Saifudheen K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy due to hyperemesis gravidarum: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics. J Postgrad Med 2016;62(4):260-263.

- 9. Michel ME, Alanio E, Bois E, Gavillon N, Graesslin O. Wernicke encephalopathy complicating hyperemesis gravidarum: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010 Mar;149(1):118-119.

- 10. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 2007 May;6(5):442-455.

- 11. Caine D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, Harper CG. Operational criteria for the classification of chronic alcoholics: identification of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997 Jan;62(1):51-60.

- 12. Chiossi G, Neri I, Cavazzuti M, Basso G, Facchinetti F. Hyperemesis gravidarum complicated by Wernicke encephalopathy: background, case report, and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006 Apr;61(4):255-268.

- 13. Netravathi M, Sinha S, Taly AB, Bindu PS, Bharath RD. Hyperemesis-gravidarum-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy: serial clinical, electrophysiological and MR imaging observations. J Neurol Sci 2009 Sep;284(1-2):214-216.

- 14. Berdai MA, Labib S, Harandou M. Wernicke’s encephalopathy complicating hyperemesis during pregnancy. Case Reports in Critical Care 2016;2016.

- 15. Thomson AD, Cook CC, Touquet R, Henry JA; Royal College of Physicians, London. The Royal College of Physicians report on alcohol: guidelines for managing Wernicke’s encephalopathy in the accident and Emergency Department. Alcohol Alcohol 2002;37(6):513-521.

- 16. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, Hillbom M, Tanasescu R, Leone MA. EFNS. EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol 2010 Dec;17(12):1408-1418.