Tobacco cigarette smoking is the primary method of tobacco consumption and represents a significant avoidable risk to public health.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), tobacco smoking is responsible for over 8 million deaths annually.2,3 Recent projections indicate that tobacco-related causes will lead to around 10 million deaths annually by 2030, with a significant majority around 70% of deaths occurring in low- and middle-income nations, and significant morbidity including cognitive impairment.2,4 Tobacco consumption in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), encompassing numerous Arab countries, including Oman, continues to pose significant public health challenges.3 This region stands out as one of the two fastest-growing regions in terms of tobacco product consumption, with anticipated prevalence rates projected to rise by 25% by 2025. In contrast, Europe, America, and Asia are expected to experience declines in tobacco use during the

same period.3

In Oman, tobacco use and secondhand smoke (SHS) related health costs more than USD 600 million in the year 2016, which represented close to 1% of the country’s gross domestic product.5 This figure underscores the substantial economic burden of tobacco-related issues in Oman. The prevalence of tobacco use in Oman has risen from 10.9% in 2000 to 13.5% in 2025.6

Among Omani youth, the prevalence of tobacco use is 1.7%, with a higher rate among males than females.5 In 2022, the age-standardized point prevalence of current tobacco smoking among individuals aged 15 years and older was estimated at 14.9% for males and 0.4% for females.3 Existing literature from Oman and other Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) countries indicates that adolescence is a key period when tobacco use is initiated.7–9 A considerable number of individuals begin smoking during adolescence, which is linked to higher risks of later developing chronic health issues, including cancer.10,11 Also, substance abuse often co-occurs with other unhealthy behaviors

in youth.12

A multifaceted interplay of social, environmental, and cognitive factors influenced the susceptibility to tobacco smoking among Omani youth.6 Some of the key factors influencing the susceptibility to tobacco smoking among Omani youth include exposure to tobacco use within the household, having friends with smoking habits, and positive beliefs about tobacco use in social gatherings.7 Conversely, exposure to anti-tobacco messages in the media decreases the susceptibility to tobacco use among young Omanis significantly.6 Therefore, tobacco use among young individuals in Oman is a significant concern necessitating urgent public health initiatives at an individual level.13

In this research, we aimed to study the current prevalence of tobacco smoking among adolescents in Oman and investigate the participants’ understanding of tobacco products and their usage, as well as their attitudes toward tobacco use and associated behaviors. Additionally, the study examined adolescents’ exposure to various forms of tobacco products, such as cigarettes, shisha, and smokeless tobacco, both at home and in school.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the prevalence of tobacco smoking and SHS exposure among adolescents in Sohar, Oman. The study was carried out between January and March 2024.

The study population comprised male students in grades 9–12 (ages 14–21) attending boys’ public schools in Sohar.

The questionnaire was adapted from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey and officially translated and validated into Arabic by the WHO.14,15 All male students in grades 9–12 from selected public schools in Sohar were eligible to participate. A computer-generated list of all boys’ public schools in Sohar was used for random selection. Girls’ public schools and private schools were excluded. In the first stage, six schools were randomly selected from all boys’ public schools in Sohar, with probability proportional to enrollment size. In the second stage, classes within these schools were randomly chosen. All students in selected classes who were present on the day of survey administration were eligible to participate. This approach ensured a representative sample of students in the specified grades. Students or parents who did not provide written consent were excluded.

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire adapted from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey, a component of the WHO Global Tobacco Surveillance System, which provides a standardized protocol for monitoring key articles of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.14 This instrument, jointly developed by the WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has an Arabic version that was validated by the WHO. It was studied in many Arabic-speaking countries and showed strong psychometric properties.15 The questionnaire is publicly available and free to use for research purposes.14

The instrument encompasses essential indicators of tobacco-related behaviors, including prevalence rates and accessibility to diverse tobacco products. It further evaluates participants’ comprehension of tobacco products, their attitudes and perceptions regarding tobacco consumption, and behavioral patterns including usage frequency, consumption contexts, procurement sources, cessation intentions, previous quit attempts, and exposure to tobacco-related media and promotional materials.14

To calculate the required sample size, we estimated the prevalence of tobacco use among the adolescent population, based on previous regional studies, to be around 15%.3,5 Using a confidence level of 95%, an absolute precision of 5%, and an anticipated non-response rate of 10%, the calculated minimum required sample size was 216 participants using the formula for single-proportion studies.

The investigators administered the paper-format questionnaires in the selected classrooms under their teachers' supervision, and responses were collected in the same sitting ensuring 100% response rate. Participants were instructed not to discuss the answers to questions while completing the questionnaire. Data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and the prevalence of tobacco use and exposure. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages.

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee at the National University of Science and Technology, Muscat (Ref: NU/COMHS/EBC005/2023). Necessary permissions were obtained from the Ministry of Education, Oman, and individual school administrations before data collection. Written informed consent from one of the parents and student assents were obtained before data collection, while ensuring voluntary participation and confidentiality. The authors ensured that all procedures complied with the ethical standards of relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the revised

Helsinki Declaration.

Results

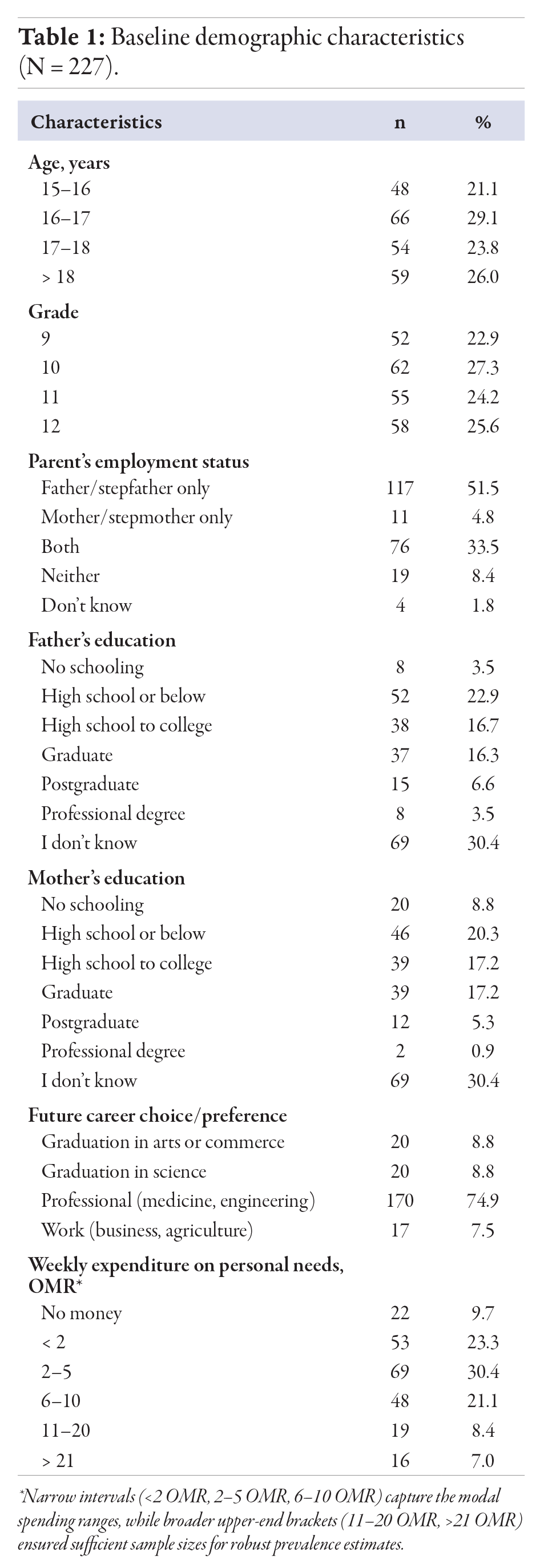

A total of 227 male students in grades 9–12 from six boys’ public schools in Sohar, Oman, participated in the study. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Their ages ranged from 15 to 18 years, with the mean age of 16.8 ± 1.3 years. The largest age group was 16–17 years, comprising 29.1% (n = 66) of the sample. The distribution of participants across grades was relatively even, although grade 10 had the highest representation at 27.3% (n = 62). When asked about parental employment, 51.5% (n = 117) reported that their father (or stepfather) was the sole working parent, while the remainder reported either a mother only or both parents working. Regarding future aspirations, 74.9% (n = 170) of students indicated a preference for professional careers, most commonly in medicine or engineering, reflecting strong ambitions toward highly skilled occupations.

Table 1

Table 1

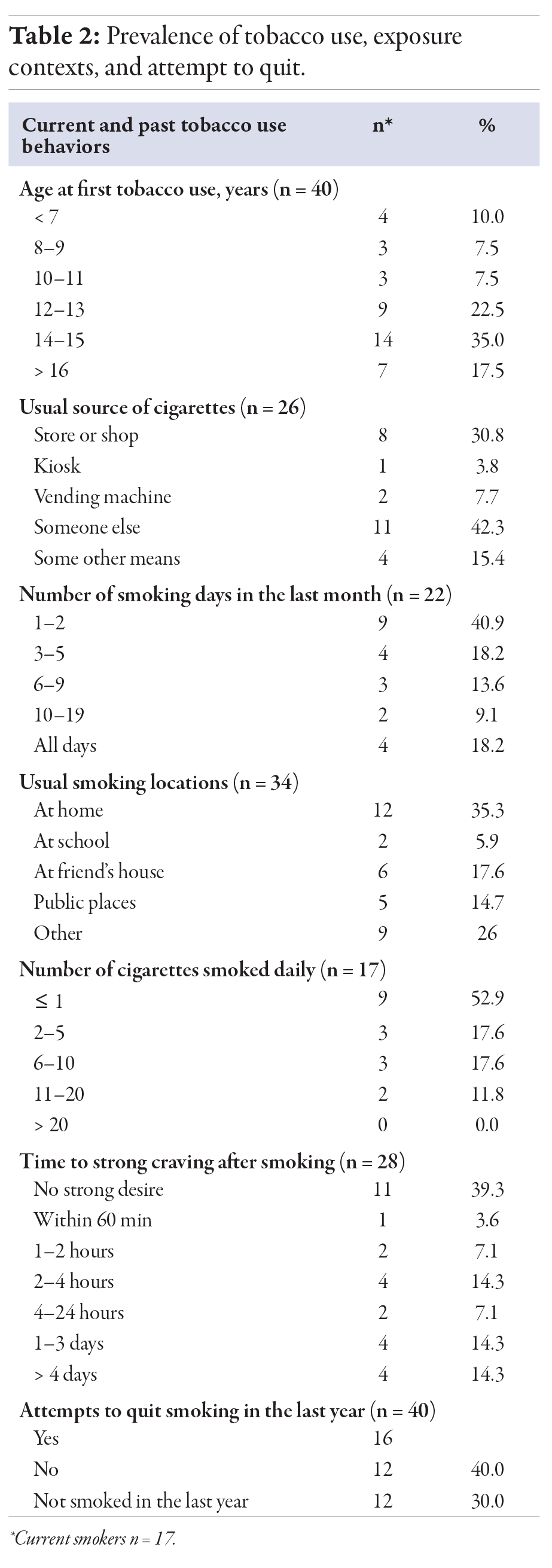

Overall, 17.6% (n = 40) of participants had tried tobacco products, and among these, the majority first experimented at 14–15 years of age [Table 2]. Current use, within the past month, was reported by 9.7% (n = 22) of participants. Smoking most often took place in private settings, with participants citing their own homes or friends’ homes as the primary locations [Table 2].

Table 2

Table 2

Exposure to SHS was relatively common in public environments. During the month preceding the survey, 42.3% (n = 96) of students encountered SHS in enclosed public spaces, and 41.4% (n = 94) in open outdoor areas. At home, 15.5% (n = 34) reported exposure over that same period. Focusing on the week before data collection, 85.0% (n = 193) experienced no SHS at home, yet 8.7% (n = 20) were exposed on three to six days, and 5.7% (n = 13) on one to two days. Notably, 10.1% (n = 23) reported encountering SHS in enclosed public spaces every day of the week, and 34.8% (n = 79) experienced SHS on school premises during the previous week. These findings highlight that public and school settings pose substantial SHS risks for adolescents, while home remains a less frequent site of exposure.

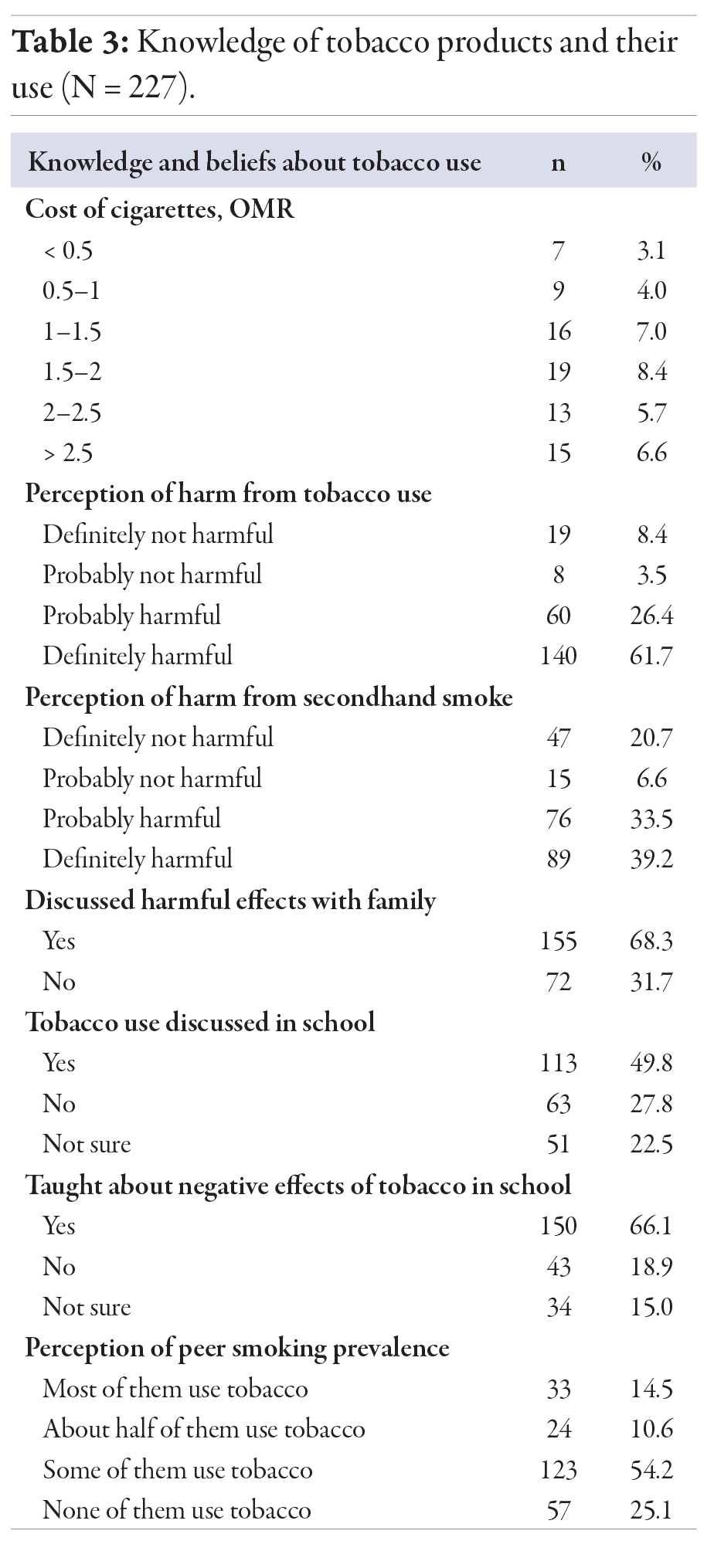

When assessing awareness of health risks in Table 3, 61.7% (n = 140) of participants perceived tobacco use as ‘definitely’ harmful. However, recognition of SHS dangers was lower: 60.8% (n = 138) did not clearly perceive SHS as harmful to their health. Family communication played a significant role, with 68.2% (n = 155) reported discussions about tobacco’s adverse effects at home, and 66.1% (n = 150) reported receiving formal instruction on tobacco harm in school. Despite this education, perceptions of peer behavior diverged: 54.2% (n = 123) believed that some of their peers used tobacco, suggesting underestimation of true peer prevalence or mixed messaging about harm.

Table 3

Table 3

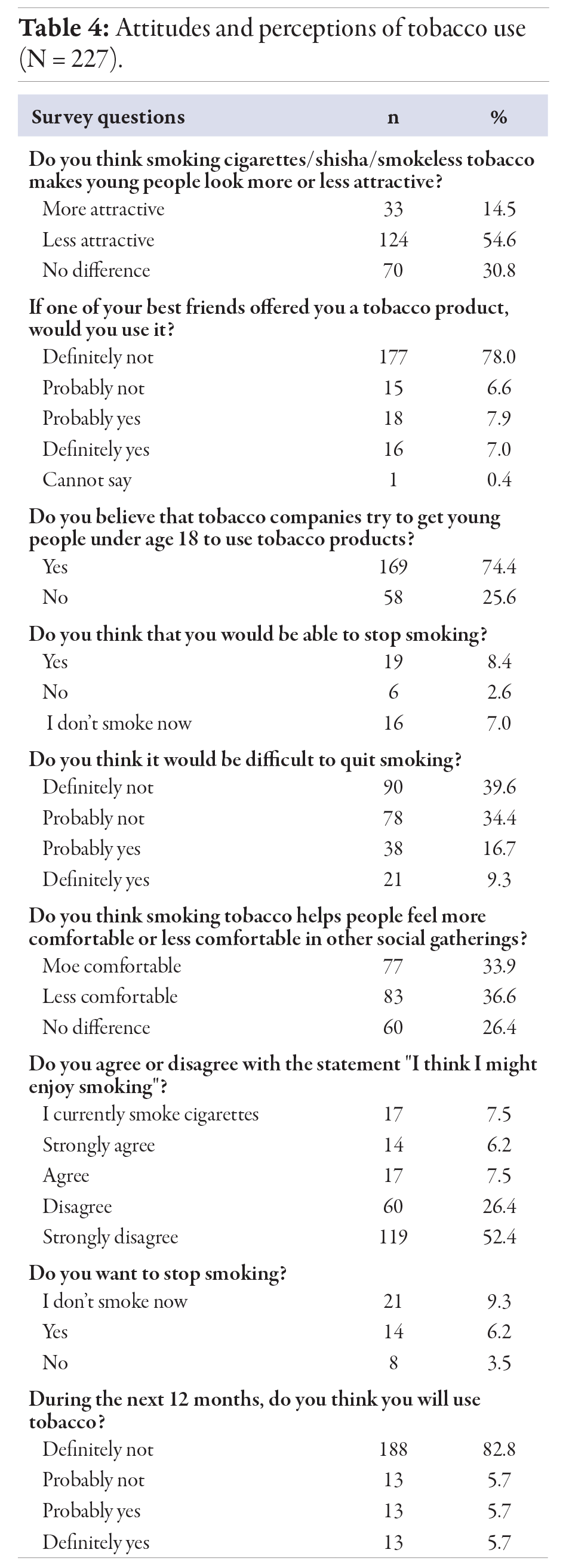

Table 4 presents data on Omani adolescents' attitudes toward tobacco use. Adolescent attitudes toward tobacco were generally defensive. When asked if they would accept a tobacco product offered by a close friend, 78.0% (n = 177) stated they would ‘definitely not’ use it. Support for smoke-free policies differed markedly by setting: 86.7% favored banning smoking in enclosed public areas, whereas only 46.2% supported bans in outdoor public spaces. Furthermore, 74.4% (n = 169) of participants believed that tobacco companies deliberately target individuals under 18 years old. In the social context, 54.6% (n = 124) agreed that smoking made young people appear less attractive among peers.

Table 4

Table 4

Discussion

This cross-sectional study highlighted the significant prevalence of tobacco exposure, particularly SHS, among adolescent males. Our findings revealed a concerning level of tobacco exposure among adolescents, emphasizing the urgent need for targeted public health interventions in this age group. These findings mirror trends observed across the GCC region, where tobacco consumption, including shisha, cigarettes, and smokeless tobacco, continues to rise among youth populations.

Our findings are consistent with the most recent WHO report, highlighting that tobacco use in 13 to 15-year age groups is a critical area of concern and emphasize the need for increased attention on SHS exposure, particularly in schools and homes.3,11

The prevalence of ever trying smoking among our participants is lower than the global average but higher than the previous estimates for Oman.6–9,11 This observation is consistent with the previous trend of a lack of significant reduction in tobacco use susceptibility among youth in Oman compared to other GCC countries.5–7 The finding that nearly two-thirds of participants did not clearly recognize the harm of SHS has significant public health implications. This low awareness may reflect broader sociocultural, educational, and policy challenges in effectively conveying the dangers of SHS to adolescents. While Oman has made progress in tobacco control, there is still significant work to be done on the policy front to target the adolescent population.11

The overall prevalence of smoking initiation in this study, with 17.6% of participants reporting having tried smoking and 7.5% currently smoking, is in line with regional trends.3,5,16 However, one of the most alarming findings is the substantial exposure to SHS, with a significant proportion of adolescents also being exposed in public spaces or enclosed areas outside the home. This corresponds with global data indicating the high rates of SHS exposure among adolescents, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.17–19 This exposure is associated with increased susceptibility to smoking initiation, reinforcing the need for stronger public health interventions.

A good level of awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco use was reported, with 61.7% of participants perceiving tobacco use as probably or definitely harmful. This suggests that educational efforts implemented in Oman have been somewhat successful. However, disconnection between knowledge and behavior highlights the complex nature of tobacco use and the need for multifaceted prevention strategies that go beyond education alone.8 Efforts to address these perceptions are critical, particularly the increasing use of non-cigarette nicotine products such as e-cigarettes and waterpipes in Oman.9,20,21

Waterpipe (shisha) smoking has historically been prevalent among older men in the EMR, who often gather in cafes to socialize and play games. In recent years, it has become increasingly popular among university students and teenagers.22 Studies have indicated that the prevalence of waterpipe smoking is notably high among adolescents in Oman (9.6%) and in the EMR (10.7%, 95% CI: 9.5–11.9) compared to the global population (6.9%, 95% CI: 6.4–7.5).9,20 In a pooled analysis of 17 Arab nations, Veeranki et al,23 reported that adolescents who used waterpipe had 2.5-times higher odds of susceptibility to cigarette smoking initiation (95% CI: 1.9–3.4). This is concerning, as previous studies indicated that waterpipe smoking can lead to higher rates of nicotine dependence and is associated with the use of other tobacco products later in life.20 Although our study did not assess waterpipe usage patterns, nearly one-third of the participants expressed an intense craving within 24 hours after smoking suggesting nicotine dependence tendency among current users.

Peer influence emerged as one of the significant factors influencing tobacco use, with 20.6% of students reporting that more than half of their friends used tobacco products. While there is strong resistance to peer pressure and an overall rejection of tobacco as a socially desirable behavior, significant misperceptions persist, particularly around the role of tobacco in social settings and the attractiveness of smoking. These findings align with previous research underscoring the role of peer pressure and social networks in the initiation and continuation of smoking behaviors. Friends’ smoking status is reported to significantly increase the odds of susceptibility in Oman (adjusted odds ratio = 3.3, 95% CI: 1.7–6.2).6 Adolescents with friends who smoke are more likely to try tobacco themselves, and this influence is compounded by the normalization of tobacco use in social settings.

The finding that three-fourths of participants believed tobacco companies try to entice people aged < 18 years to use tobacco products validates with global concerns about industry targeting of young people.24 Recent estimates of the costs of tobacco use and SHS highlight the economic burden of tobacco-related issues in Oman.4,11 Despite making considerable progress, Oman remains the only GCC state without comprehensive tobacco control legislation.11,23 The awareness among Omani adolescents in this area is encouraging and suggests that education efforts about industry tactics may be having some impact. However, it also underscores the ongoing need for vigilance and robust policies to counter industry influence, as highlighted by the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.14 Interestingly, while most participants expressed support for banning smoking in enclosed public spaces, fewer supported a ban on smoking in outdoor public areas. This may indicate a lack of awareness of the dangers of SHS in outdoor settings, where exposure can still have significant health consequences.

Our findings align with the broader literature, which indicates that older adolescents and those with parents who smoke are at higher risk of tobacco use. Alves et al,25 reported that children with two smoking parents were more likely to start smoking as early as 13 years old and to become daily smokers. This risk was attributed to a higher chance of transitioning from early smoking stages to daily smoking. Furthermore, students with higher weekly allowances were more likely to smoke, which supports the previous observation that disposable income may facilitate access to tobacco products in Oman.9

Our results provide the latest data on tobacco use and exposure among adolescent males in Oman, filling a crucial gap in the literature.11 Although the study is restricted to male students from public schools in Sohar, limiting the generalizability of findings, the use of a standardized, internationally validated instrument allows for regional and cross-national comparisons. The cross-sectional nature of the study precludes the determination of temporal sequences and the inferences of factors associated with tobacco use. Self-reported data on tobacco use may be subject to social desirability bias, potentially leading to underreporting of tobacco use. Additionally, the use of cigarettes, shisha, or smokeless tobacco was not assessed separately, limiting our ability to examine product-specific patterns and risk factors.

Conclusion

Many Omani adolescent males have experimented with tobacco, and several factors that may influence tobacco initiation among youth in Oman. This research addresses the WHO’s call for countries to establish robust monitoring systems. By analyzing of adolescents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices, this study provides evidence-based insights to inform targeted prevention policies and counter tobacco industry marketing strategies.18

The high prevalence of SHS also highlights an urgent public health issue. Efforts to limit tobacco use in this population should focus on enhancing awareness of the dangers of SHS, particularly in outdoor, home environments, and indoor public spaces, including restaurants, cafes, and other gathering places frequented by youth. The divided opinions on outdoor smoking bans suggest a need for targeted education about the risks of SHS in all environments.24

We recommend key areas for intervention that include strengthening smoke-free policies, particularly in public spaces frequented by youth, and developing targeted prevention programs for early adolescents (14–15 years).12,26 Social influences on tobacco use, including peer pressure and family smoking habits, need due consideration in such interventions. Long-term follow-up studies are required to track changes in tobacco use patterns and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. Future studies should include female students, private schools, and other regions of Oman to provide a more comprehensive national representation. Qualitative studies could further offer deeper insights into the social and cultural factors influencing tobacco use among Omani youth.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2021 Jun;397(10292):2337-2360.

- 2. World Health Organization. Tobacco. 2023 [cited 2024 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

- 3. World Health Organization. World Health Organization global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000–2030. 2024 [cited 2024 June]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240088283.

- 4. Muhammad F, Ummah AS, Aisyah F, Danuaji R, Mirawati DK, Subandi S, et al. Active and passive smoking as catalysts for cognitive impairment in rural Indonesia: a population-based study. Oman Med J 2024 Jul;39(4):e655.

- 5. Koronaiou K, Al-Lawati JA, Sayed M, Alwadey AM, Alalawi EF, Almutawaa K, et al. Economic cost of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Tob Control 2021 Nov;30(6):680-686.

- 6. Monshi SS, Wu J, Collins BN, Ibrahim JK. Youth susceptibility to tobacco use in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, 2001-2018. Prev Med Rep 2022 Jan;26:101711.

- 7. Al Riyami AA, Afifi M. Smoking in Oman: prevalence and characteristics of smokers. East Mediterr Health J 2004;10(4-5):600-609.

- 8. Al Omari O, Abu Sharour L, Heslop K, Wynaden D, Alkhawaldeh A, Al Qadire M, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, prevalence and associated factors of cigarette smoking among university students: a cross sectional study. J Community Health 2021 Jun;46(3):450-456.

- 9. Al-Lawati JA, Muula AS, Hilmi SA, Rudatsikira E. Prevalence and determinants of waterpipe tobacco use among adolescents in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2008 Mar;8(1):37-43.

- 10. Berkman AM, Andersen CR, Roth ME, Gilchrist SC. Cardiovascular disease in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: impact of sociodemographic and modifiable risk factors. Cancer 2023 Feb;129(3):450-460.

- 11. Razzak HA, Harbi A, Ahli S. Tobacco smoking prevalence, health risk, and cessation in the UAE. Oman Med J 2020 Jul;35(4):e165.

- 12. Mbarki O, Ghammem R, Zammit N, Ben Fredj S, Maatoug J, Ghannem H. Cross-sectional study of co-occurring addiction problems among high school students in Tunisia. East Mediterr Health J 2023 Dec;29(12):924-936.

- 13. Al-Kalbani SR. Overview of tobacco cessation service in Oman: a narrative review. Tob Prev Cessat 2025 Mar;11.

- 14. World Health Organization. Global youth tobacco survey. 2023 [cited 2024 July]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-youth-tobacco-survey.

- 15. Ayedi Y, Harizi C, Skhiri A, Fakhfakh R. Linking global youth tobacco survey (GYTS) data to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control (FCTC): the case for Tunisia. Tob Induc Dis 2022;20:07.

- 16. Monshi SS. Examining tobacco control policies in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. PhD Thesis, 2021, Temple University, Philadelphia, USA. p. 54-60.

- 17. Ma C, Heiland EG, Li Z, Zhao M, Liang Y, Xi B. Global trends in the prevalence of secondhand smoke exposure among adolescents aged 12-16 years from 1999 to 2018: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2021 Dec;9(12):e1667-e1678.

- 18. Al-Zalabani AH. Secondhand smoke exposure among adolescents in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries: analysis of global youth tobacco surveys. Sci Rep 2024 Sep;14(1):21534.

- 19. World Health Organization. Tobacco free initiative. [cited 2024 September]. Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/tfi/news/oman-bans-waterpipes-and-creates-national-awareness-during-covid-19.html.

- 20. Neergaard J, Singh P, Job J, Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence. Nicotine Tob Res 2007 Oct;9(10):987-994.

- 21. Awada Z, Cahais V, Cuenin C, Akika R, Silva Almeida Vicente AL, Makki M, et al. Waterpipe and cigarette epigenome analysis reveals markers implicated in addiction and smoking type inference. Environ Int 2023 Dec;182:108260.

- 22. Ma C, Yang H, Zhao M, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Prevalence of waterpipe smoking and its associated factors among adolescents aged 12-16 years in 73 countries/territories. Front Public Health 2022 Nov;10:1052519.

- 23. Veeranki SP, Alzyoud S, Kheirallah KA, Pbert L. Waterpipe use and susceptibility to cigarette smoking among never-smoking youth. Am J Prev Med 2015 Oct;49(4):502-511.

- 24. Al-Lawati JA, Bialous SA. Tactics of the tobacco industry in an Arab nation: a review of tobacco documents in Oman. Tob Control 2023 May;32(3):308-314.

- 25. Alves J, Perelman J, Ramos E, Kunst AE. Intergenerational transmission of parental smoking: when are offspring most vulnerable? Eur J Public Health 2022 Oct;32(5):741-746.

- 26. Al-Mahrouqi T, Al-Ghailani F, Al-Maqbali M, Al Saidi M, Prashanth GP. A cluster randomized trial comparing photoaging app and school based educational intervention for tobacco use prevention in adolescents. Sci Rep 2025 May;15(1):15374.