Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hereditary blood disorder classified as a hemoglobinopathy. This lifelong disorder is associated with many complications affecting multiple body systems.1 In SCD, crescent-shaped red blood cells block the flow of blood to tissues, leaving them without enough oxygen.2,3

The main genetic types of SCD include hemoglobin SS, which is the most severe form, hemoglobin SC, and hemoglobin S beta thalassemia. Globally, the birth prevalence of SCD is estimated at 112 per 100 000 live births. Higher rates are reported in Africa, with 1125 per 100 000 live births, and in Europe with an estimated 43.12 per 100 000 live births. The number of individuals living with SCD globally increased from approximately 5.46 million in 2000 to about 7.74 million in 2021—a 41.4% increase. Meanwhile, the total number of neonates diagnosed annually rose by 13.7%, to approximately 515 000, driven mainly by population growth in the Caribbean and western and central sub-Saharan Africa.4 These statistics illustrate the critical global burden of SCD on children, which highlights the need for targeted health interventions and evaluates the current management protocols.5 In the United States of America, the SCD Association estimates that 70 000 to 100 000 individuals have SCD, and about 3 million carry the trait.6 SCD predominantly affects African Americans according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with 1 in 500 African Americans affected, compared with 1 in 36 000 Hispanic Americans. Additionally, 1 in 13 African Americans carries the sickle cell trait.6

In Oman, SCD is a prevalent genetic blood disorder that increases the mortality and morbidity rates.7 According to the Ministry of Health 2020 Annual Health Report, 309 school-age children are diagnosed with SCD each year and 286 preschool children were newly diagnosed, likely due to high rates of consanguinity marriages.8 The birth prevalence of sickle cell trait in Oman is 6%, while beta-thalassemia is 2%, and SCD itself affects 0.2% of the population. Mortality is high, particularly in children under age five, with over 81 000 SCD-related deaths globally in 2021.4,9 These statistics underscore the urgent need for improved screening, early intervention, and better access to effective treatments such as hydroxyurea.4

SCD causes various complications that negatively affect HRQOL in children. HRQOL is a significant patient-reported outcome in children and provides a detailed concept of SCD burden on children with SCD. Moreover,10 it is a significant predictor of morbidity and mortality. One of these complications is a vaso-occlusive crisis, which is characterized by sharp and intense pain.11 Vaso-occlusive pains occur around six times per year in children with SCD, and this pain may last up to four days.12,13

Painful episodes differ in prevalence and intensity.14 Managing these painful episodes mainly starts in patients’ homes, and sometimes, patients need hospital admission if the pain is persistent.14 Vaso-occlusive painful episodes typically manifest as pain in the chest, back, or lower or upper limbs.13 Extreme cold or hot environments, dehydration, the presence of other illnesses, and stress trigger these events.15 Due to frequent vaso-occlusive pain events, children with SCD tend to have lower baseline HRQOL than healthy children.15,16 SCD varies in severity (mild to severe); therefore, children with the more severe type of SCD usually present with worse HRQOL than those with the mild disease. Penicillin and blood transfusions are the usual treatments for children with SCD.15 Recently, experts have recommended hydroxyurea drug therapy for patients with SCD. Hydroxyurea is a promising treatment option for SCD patients for reducing disease complications.17 Although this medicine does not cure the disease, it does help make fetal hemoglobin (Hb F), which improves circulation and lowers the number of vaso-

occlusive events.

Research has found that the use of hydroxyurea is associated with improvements in HRQOL.15 Hydroxyurea has been studied and found to reduce chest syndrome episodes, painful crises, and the need for frequent blood transfusions or hospital stays.10 Moreover, hydroxyurea could delay spleen infarction, kidney, lung, or even brain damage. It was found that the hydroxyurea drug could help the red blood cells remain stable and more flexible. Therefore, the red blood cells flow easily, even in tiny vessels. This occurs because hydroxyurea raises the level of Hb F, and thus, red blood cells do not change to a crescent shape. This results in fewer complications of the disease and better HRQOL of children with SCD.7,10,15

Research has suggested that children who were put on hydroxyurea became stable and quite asymptomatic, which decreased the burden of the disease among families and positively impacted the children’s HRQOL. A cross-sectional study was conducted among children aged 3 to 18 years old to assess HRQOL in children with SCD.18 Children in this study rated their HRQL less than their parents, but with no significant difference, except for social functioning (p = 0.047). Recruitment of children was conducted at hematology clinics, where they were requested to fill out the PedsQL survey. This study presented a significant difference (p < 0.001) in the total score of HRQOL of children who were taking the treatment daily (HRQOL score median = 75; IQR = 62.0–86.4) and those not (HRQOL score median = 69.0; IQR = 54.1–81.6). The study also proved that physical activities were significantly less when compared with those who did not start hydroxyurea (median = 71.4, IQR = 58.6; p < 0.001) than in children who were on hydroxyurea (median = 79.7; IQR = 62.5).17 The non-users had several interferences with school attendance and lower scores in the physical domain compared to children who were adherent to the hydroxyurea drug.17 Children who did not use hydroxyurea had frequent pain crises and complications that interfered with regular school attendance.17

Similarly, a qualitative study on medication adherence among children was conducted, involving 10 children and adolescents.19 The study found that children experienced memory lapses, lacked self-management, and encountered barriers in their social life. This highlighted that HRQOL is affected among children with SCD. The researchers concluded that SCD children experience several barriers to medication adherence and urged the necessity for a comprehensive treatment plan to analyze the children’s issues around medication adherence, which results in better HRQOL.

A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia concluded that children with low adherence to hydroxyurea perceived higher benefits in disease control (mean ± SD = 5.77 ± 2.99).1 Another three studies investigated the impact of hydroxyurea adherence on the HRQOL among children with SCD.11,16 The studies investigated the predictors of HRQOL in 78 with SCD (mean ± SD = 11.3 ± 3.92 years). Children completed the PedsQL during a clinic visit. The Adherence and Self-Care Inventory tool was utilized to measure treatment adherence. Results revealed that HRQOL is correlated with hydroxyurea adherence (R = 0.88). Adherence to hydroxyurea was a significant predictor of the improvement in the HRQOL scores.11,16

Not all children in Oman are prescribed hydroxyurea, and there is limited information about its use and HRQOL among children with SCD. Therefore, further assessment of HRQOL's impact is deemed important to examine its effects on HRQOL among children with SCD. In addition, no similar studies have been conducted in Oman, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of this kind. Therefore, this study sought to investigate the differences in HRQOL between children on hydroxyurea treatment and those not on treatment. We hypothesized that children receiving hydroxyurea would report higher HRQOL scores and that hydroxyurea use would significantly predict

improved HRQOL.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included children aged 8–12 years from the Royal Hospital’s hematology clinic in Oman. Participants were selected via simple random sampling based on even-numbered entries in clinic appointment lists. Sample size was determined using Slovin’s formula with a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error, accounting for a 10% attrition rate. A sample of 74 was deemed appropriate.

We used HRQOL-SCD (43 items, 9 domains, reliability = 0.93) and HRQOL-Generic (PedsQL, 23 items, 4 domains, reliability = 0.95). Both tools were validated in prior studies on children

with SCD.20,21,22

SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used for data analysis. Scores were reverse-scored to a 0–100 scale; higher scores indicated better HRQOL. Normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and independence of errors were tested. One-way analysis of variance and analysis of covariance were conducted, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Linear regression identified predictors of HRQOL.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ministry of Health (MOH/CSR/22/25828). Informed assent and consent were collected from children and their parents, respectively. Children were asked to fill in the two tools on HRQOL (child versions).

Results

A total of 74 children (47.3% male, 52.7% female) completed the questionnaire; 33 were on hydroxyurea and 41 were not [Table 1]. A one-way analysis of variance was conducted to investigate the differences in HRQOL of children who receive hydroxyurea in comparison to those who do not.

Table 1: Children’s demographics, N = 74.

|

Age, mean ± SD, years

|

10.0 ±1 .3

|

|

Sex

|

|

Male

|

35 (43.7)

|

|

Female

|

39 (52.7)

|

|

On hydroxyurea

|

33 (44.6)

|

The findings revealed a significant difference in HRQOL scores [Table 2] between children receiving hydroxyurea and those not (HRQOL-SCD) (F (1, 68) = 419.4; p < 0.001). Children on hydroxyurea reported higher HRQOL scores than children who were not (69.3 ± 10.1 and 51.5 ± 7.9, respectively).

Similarly, the findings showed no significant difference in HRQOL scores reported on the PedsQL-generic (F(1,68) = 239.8; p = 0.300). Children on hydroxyurea reported higher HRQOL scores than children who were not (68.5 ± 11.9 and 61.9 ± 14.9, respectively).

Table 2: Mean differences in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores (N = 33).

|

HRQOL-SCD

|

|

|

On hydroxyurea

|

69.3 ± 10.1

|

|

Not on hydroxyurea

|

51.5 ± 7.9

|

|

HRQOL-Generic

|

|

|

On hydroxyurea

|

68.5 ± 11.9

|

|

Not on hydroxyurea

|

61.9 ± 14.9

|

|

Female (n = 17) on hydroxyurea

|

69.0 ± 11.1

|

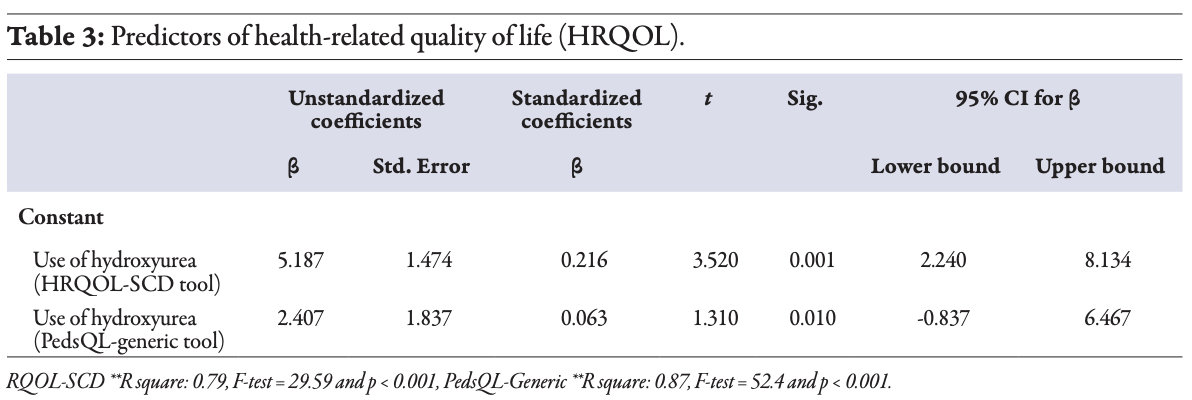

Furthermore, the study identified the predictors of HRQOL, and hydroxyurea appeared as a significant predictor for the improvement of HRQOL in children with SCD. Compliance with the hydroxyurea drug

(β = 2.40, t = 1.31, p = 0.010, partial η2 = 0.16) was a significant predictor of the child-reported HRQOL-GENERIC. The R2 of 0.87 showed that 87.0% of the variability in the child-reported HRQOL-GENERIC was explained by parental familiarity, self-efficacy, child sex, and receiving hydroxyurea (R2 = 0.87, F (8,69) = 52.4; p-value < 0.001) [Table 3].

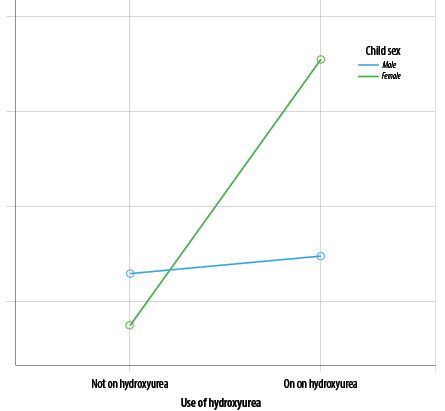

Furthermore, the use of the hydroxyurea drug appeared to be a significant predictor in the HRQOL-SCD disease-specific tool (β = 5.18, t = 3.52; p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.41). The R2 of 0.79 indicated that 79.0% of the variability in the child-reported HRQOL-SCD was accounted for by parental familiarity, self-efficacy, child gender, and use of hydroxyurea (R2 = 0.79, F (8,69) = 29.59; p < 0.001) [Table 3]. In addition, the study examined a three-way interaction between sex, hydroxyurea, and HRQOL scores. The results showed that females on hydroxyurea reported higher HRQOL scores than male children (69.0 ± 11.1 and 64.7 ± 14.0, respectively); however, the difference was not significant. Figure 1 suggests a non-significant interaction between sex, hydroxyurea, and HRQOL (F (1,68) = 238.8; p = 0.500).

Table 3

Table 3

Figure 1: Three-way interactions between sex, hydroxyurea, and health related quality of life scores.

Figure 1: Three-way interactions between sex, hydroxyurea, and health related quality of life scores.

Discussion

This study contributes valuable evidence on HRQOL in Omani children with SCD. Moreover, the uniqueness of the study is that females showed higher HRQOL. The findings align with global research: hydroxyurea improves HRQOL, reduces complications, and enhances

overall well-being.15,18

The results of the study indicated that children with SCD who were receiving hydroxyurea reported higher HRQOL scores than children not using the drug. Our findings were similar to those of other studies, which found that hydroxyurea users had higher QOL scores than non-users.11

The non-users had several interferences with school attendance and lower scores in the physical domain. Also, similar findings were reported in previous studies, which concluded that participants with higher hydroxyurea adherence perceived more benefits and had better emotional outcomes.16 The results from those studies revealed that adolescents with more negative perceptions of using hydroxyurea reported worse fatigue, pain, anxiety, and depression. Our findings showed that hydroxyurea was a significant predictor of the improvement in HRQOL. The finding is consistent with other studies, which identified hydroxyurea as a significant predictor for the improvement of QOL scores.22 In addition, the study concluded that adherence to the drug was a significant predictor of improvement in the

HRQOL scores.22

The finding has demonstrated that the use of hydroxyurea is associated with improvements in HRQOL. It was found that hydroxyurea treatment increases the amount of Hb F, and therefore, red blood cells are less likely to change into a sickle shape. This, in turn, leads to fewer complications of the disease and improves the HRQOL of children with SCD.23,24 Furthermore, females on hydroxyurea reported slightly better outcomes, possibly due to higher adherence, although this warrants

further exploration.

The study was a cross-sectional investigation and the data was collected only at one point in time. The small sample size limits the generalization of the findings. In addition, we did not measure medication adherence. We did not evaluate healthcare utilization for SCD patients, including number of visits and hospitalization, to correlate them with hydroxyurea use. Future studies should use randomized controlled trials with larger samples and examine additional variables such as hospitalizations and Hb F levels.

Conclusion

The use of hydroxyurea was associated with an improvement in HRQOL; children with SCD who were compliant with hydroxyurea reported higher HRQOL scores than children who were not using the drug. Hydroxyurea treatment results in fewer complications of the disease and better HRQOL in children with SCD. Therefore, we recommend enhancing parents’ understanding of the significance of hydroxyurea and devising strategies to promote children’s medication adherence. It is recommended to include in the SCD management protocol that all children with SCD take hydroxyurea drugs to reduce disease complications and improve their HRQOL.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study. Written informed consent was obtained from one of the patient's parents, and an assent form was taken from the children who participated in the study.

references

- 1. Madkhali MA, Abusageah F, Hakami F, Zogel B, Hakami KM, Alfaifi S, et al. Adherence to hydroxyurea and patients’ perceptions of sickle cell disease and hydroxyurea: a cross-sectional study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024 Jan;60(1):124.

- 2. Panepinto JA, Torres S, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019;66(11):277-289.

- 3. Smaldone A, Manwani D, Green NS. Greater barriers to hydroxyurea (HU) associated with poorer health related quality of life (HRQL) in youth with sickle cell disease. Blood 2018 Nov;132:160.

- 4. Thomson AM, Kassebaum NJ, Nicholas M, Naghavi M, McHugh S; GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Haematol 2023 Aug;10(8):e585-e599.

- 5. Wastnedge E, Waters D, Patel S, Morrison K, Goh MY, Adeloye D, et al. The global burden of sickle cell disease in children under five years of age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2018 Dec;8(2):021103.

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is sickle cell disease? | CDC. 7 [cited 2022 August 18]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/facts.html.

- 7. Al Nasiri YA, Al Mawali AH. Health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: a concept analysis. J Contemp Med Sci 2019;5(1):59-63.

- 8. Ministry of Health. Annual health report 2020. 2024 [cited 2024 January 28]. Available from: https://moh.gov.om/en/statistics/annual-health-reports/annual-health-report-2020/.

- 9. Wali Y, Kini V, Yassin MA. Distribution of sickle cell disease and assessment of risk factors based on transcranial Doppler values in the Gulf region. Hematology 2020 Dec;25(1):55-62.

- 10. Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Alakwe-Ojimba CE, Elendu TC, Elendu RC, Ayabazu CP, et al. Understanding sickle cell disease: causes, symptoms, and treatment options. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023 Sep;102(38):e35237.

- 11. Tarazi RA, Patrick KE, Iampietro M, Apollonsky N. Hydroxyurea use is associated with executive functioning and nonverbal skills in young children with sickle cell disease (SCD). Authorea 2020.

- 12. Di Maggio R, Hsieh MM, Zhao X, Calvaruso G, Rigano P, Renda D, et al. Chronic administration of hydroxyurea (HU) benefits Caucasian patients with sickle-beta thalassemia. Int J Mol Sci 2018 Feb;19(3):681.

- 13. Ballas SK. How I treat acute and persistent sickle cell pain. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020 Sep;12(1):e2020064.

- 14. Gollamudi J, Karkoska KA, Gbotosho OT, Zou W, Hyacinth HI, Teitelbaum SL. A bone to pick-cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone pain in sickle cell disease. Front Pain Res (Lausanne) 2024 Jan;4:1302014.

- 15. Sendy JS, Alsadun MS, Alamer SS, Alazzam SM, Alqurashi MM, Almudaibigh AH. Frequency of painful crisis and other associated complications of sickle cell anemia among children. Cureus 2023 Nov;15(11):e48115.

- 16. Mwazyunga Z, Ambrose EE, Kayange N, Bakalemwa R, Kidenya B, Smart LR, et al. Health-related quality of life among children with sickle cell anaemia in Northwestern Tanzania. Open J Blood Dis 2022 Jun;12(2):11-28.

- 17. Bailey M, Bonner AD, Brown S, Thompson M. PRO91 reduction in HRQOL with increasing VOC frequency among patients with SCD. Value Health 2020;23:S345.

- 18. Kuriri FA. Hope on the horizon: new and future therapies for sickle cell disease. J Clin Med 2023 Sep;12(17):5692.

- 19. Abadesso C, Pacheco S, Machado MC, Finley GA. Health-related quality of life assessments by children and adolescents with sickle cell disease and their parents in Portugal. Children (Basel) 2022 Feb;9(2):283.

- 20. Curtis K, Lebedev A, Aguirre E, Lobitz S. A medication adherence app for children with sickle cell disease: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019 Jun;7(6):e8130.

- 21. Sousa KH, Kwok OM. Putting Wilson and cleary to the test: analysis of a HRQOL conceptual model using structural equation modeling. Qual Life Res 2006 May;15(4):725-737.

- 22. Al Sabbah M, Radaideh M, Saleh SM, Al-Doory SA, Abdalqader AM, Mir FF, et al. Is hydroxyurea treatment changing the life of children with sickle cell disease? Dubai Med J 2023;6(4):301-309.

- 23. Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Lai JS, Penedo FJ, Rychlik K, Liem RI. Health-related quality of life and adherence to hydroxyurea in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017 Jun;64(6):e26369.

- 24. Al Sayigh NA, Shafey MM, Alghamdi AA, Alyousif GF, Hamza FA, Alsalman ZH. Health-related quality of life and service barriers among adults with sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2023 Sep;33(5):831-840.