Dermatitis artefacta (DA) is a deliberate and conscious self-inflicted cutaneous injury. It is a rare pathology of skin lesions characterized by patients’ denial of all responsibility in their causation.1 Depending on the methods used, lesions are often bizarrely shaped, usually oddly distributed on the body and, most of the time, are produced at sites easily accessible to the patients.2 DA was first described in the modern literature in 1951.3

The pathophysiology of DA is poorly understood. Genetics, psychosocial factors, as well as a personal and family history of psychiatric illness, have all been implicated as causes of the condition.4 Events thought to be the triggers for these self-inflicting injuries can range from simple anxiety to more serious interpersonal conflicts and severe personality disorders.5 It is believed that patients produce these skin lesions as a form of self-expression to satisfy a psychological need. Often this is a desire to receive medical treatment6 or to assume a sick role.3

DA is a rarely diagnosed disorder. The overall incidence is unknown, although it is much more common in adolescent girls and much less common in males.7 However, it has been reported in all age groups including children8-10 and the elderly.11

DA differs from other skin disorders in that lesions do not conform to those of known skin conditions. Patients with these lesions are otherwise healthy and all laboratory tests are usually normal. The diagnosis is made by suspicion and exclusion rather than on the basis of histological or biochemical findings. Thus, it involves a considerable investment in time and resources, and because of a lack of awareness of the disorder, it is often a source of anxiety for physicians.1

Here we report a case of recurrent skin lesions typical of DA appearing in the left lower limb of a 33-year-old Omani male for nine years.

Case report

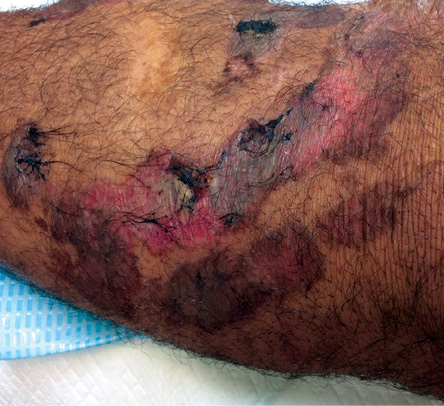

Figure 1: Horseshoe-shaped superficial crusted lesions on the left lower leg of a 33-year-old male with three identical linear bullae above the knee joint.

Figure 2: Close-up of superficial lesions in the left lower leg of a 33-year-old male showing different stages of healing with normal looking skin around them.

A 33-year-old Omani male presented with recurrent left leg lesions over a period of nine years. The patient gave precise timing of when the most recent skin eruptions started. First two lesions spontaneously erupted and then increased in number in the same area. He claimed to have fever, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and dizziness. He was admitted to Sohar Hospital and treated for a skin infection with antibiotics. The lesions recovered completely after three days. Lesions then reappeared around the same area, repeatedly.

He was treated and hospitalized because of this problem many times in different hospitals. According to the patient, biopsies taken from the lesions, as well as microbiological and biochemical tests, were all normal. His lesions apparently disappeared shortly after admission to the hospitals.

The patient travelled abroad for the same problem and, once again, no definitive diagnosis was made despite the many tests performed. He was diagnosed with skin infection and treated with antibiotics and according to the patient there was a complete disappearance of the lesions.

The latest episode of skin eruptions started to appear three weeks prior to his consultation with the infectious disease and dermatology clinics at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital. He gave a history of fever, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue most of the time. He also reported that it had been difficult for him to walk. On further questioning, the patient appeared to have knowledge of where the next lesions would appear. He pointed to a healthy area of the skin near the old lesions. He had been on sick leave for a considerable time and had not worked consistently for the last six months.

Assessment showed no fever and other vital parameters were all normal. Examination of the left leg showed mild erythema with trivial swelling and superficial crusted linear erosions on the medial and lateral aspects forming a horseshoe shape below the knee. There were three well-demarcated, well-spaced identical linear bullae on erythematous bases above the knee joint on the medial side of the thigh [Figure 1]. The lesions on the knee joint and below were at different stages of healing [Figure 2].

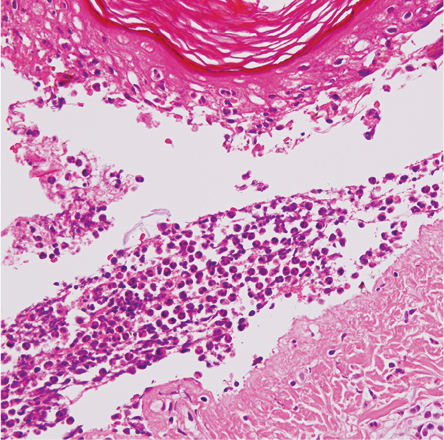

Figure 3: Biopsy of blisters showing necrosis of epidermis and superficial dermis, magnification=40×.

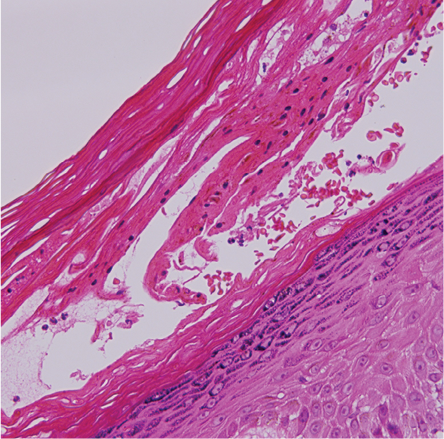

Figure 4: Biopsy of erosions showing necrosis of keratinocytes with evidence of healing by regeneration underneath, magnification=40×.

The rest of the skin in-between the lesions and elsewhere in the body was completely normal. Examination of the rest of the body was unremarkable.

Microbiological tests were ordered including blood cultures and lesion swab cultures, and serological tests for tuberculosis, retroviruses, chronic hepatitis, and other viruses. Biochemical tests were done including kidney and liver function tests and bone biochemistry tests. The results of these tests were normal.

Two punch biopsy specimens were taken, one from the blisters and a second from the erosions. The microscopic findings from the blisters showed epidermal necrosis with abundant neutrophils with keratinocyte necrosis. The dermis showed moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltration. The papillary dermis showed some coagulative necrosis beneath the blister. There were no

microabscesses [Figure 3].

The findings from the erosions revealed a subcorneal cleft made up of necrotic keratinocytes covered by a thick orthokeratotic horny layer at the roof. The dermis showed mild perivascular lymphocytes infiltrate [Figure 4].

The sections taken from the two sites show two evolving lesions including subepidermal blister with necrosis of epidermis at one site and healing lesion with evidence of transepidermal elimination at the other site. These blisters were due to necrosis of the epidermis and were negative for immunofluorescence. Hence, these findings were compatible with a diagnosis of artefactual condition.

In our case, given the long history of recurrent lesions, their appearance, shape, and location in area of skin easily accessible to the patient, in addition to the pathological findings and normal tests, a diagnosis of DA was made. A psychiatric assessment was then sought for the patient.

Discussion

In DA the patient creates skin lesions to satisfy an internal psychological need and denies all responsibility. Patients often go undiagnosed for some time until the observation of bizarre or unusual skin changes combined with a non-specific histology and normal test results lead to a diagnosis. Patients with DA waste time and resources with unnecessary tests resulting in high costs to the healthcare system.12

Box 1: Typical clinical findings and features of dematitis artefecta.

In our patient, there was a long history of recurrent skin lesions with no obvious cause. After repeated consultations and assessment of the patients’ medical history and physical signs, patients with DA can be identified because of certain classic features [Box 1].2,9,11,12 Often there is a hollow history since patients will not give a timeline or an evolution pattern for the current skin lesions, which leads to the impression that they appeared without any preceding causative factors.11

On physical examination, lesions can vary as much as the creativity behind their cause. Lesions often are bizarrely shaped, oddly distributed, and appear at sites accessible to the patient.2 Overall the pattern of presentation of lesions is secondary to the mechanism of injury and can include blisters, excoriations, superficial erosions, ulcers, abrasions, ecchymosis, purpura, erythema, edema, or signs of trauma and burns.9,11,12 Differential diagnosis may vary greatly depending on the methodology and type of skin lesions produced by the patient. The various methods of producing the skin lesions are highly imaginative and depend on the patient’s background and education.13

Increased awareness of DA can save physicians, patients, and family members many frustrating medical visits and allow for better management and treatment of the condition. Management of these patients should be sympathetic and start with indirect indication that their activities are known. Direct confrontation should be avoided.14 Patients should be seen frequently to establish a good relationship, which is important as many patients are often lost to follow-up.15,16

Isolation and failure to communicate makes it difficult to help these patients.14 Psychiatric evaluation is essential as patients with DA often show signs of personality disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders, depression, impulsive behavior, and somatization.17 Thus, in order to deliver the best management of these patients consultations with dermatologists and psychiatrist are essential, as in the case of this patient.

Conclusion

DA is a rare self-inflected skin condition that can affect all ages and both genders, although it is more common in young women. Understanding, recognizing, diagnosing, and managing this condition properly is vital to avoid the frustration that commonly results from DA and avoid repeating lengthy, time consuming, and expensive tests and focus on resolving the precipitating factors.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

references

- Rodríguez Pichardo A, García Bravo B. Dermatitis artefacta: a review. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2013 Dec;104(10):854-866.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Haberman HF. The self-inflicted dermatoses: a critical review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1987 Jan;9(1):45-52.

- Gattu S, Rashid RM, Khachemoune A. Self-induced skin lesions: a review of dermatitis artefacta. Cutis 2009 Nov;84(5):247-251.

- Cotterill JA, Millard LG. Psychocutaneous Disorders. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Textbook of Dermatology. 6th Edition Vol 4. Oxford: Blackwell; 1998. p. 2785-2813.

- Nayak S, Acharjya B, Debi B, Swain SP. Dermatitis artefacta. Indian J Psychiatry 2013 Apr;55(2):189-191.

- Koblenzer CS. Dermatitis artefacta. Clinical features and approaches to treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2000 Jan-Feb;1(1):47-55.

- Mariyath R, Kumar P. Dermatitis artefacta-A focal suicide. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2003;69(S1):73-74.

- Kumaresan M, Rai R, Raj A. Dermatitis artefacta. Indian Dermatol Online J 2012 May;3(2):141-143.

- Saez-de-Ocariz M, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Mora-Magaña I, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, et al. Dermatitis artefacta in pediatric patients: experience at the national institute of pediatrics. Pediatr Dermatol 2004 May-Jun;21(3):205-211.

- Rogers M, Fairley M, Santhanam R. Artefactual skin disease in children and adolescents. Australas J Dermatol 2001 Nov;42(4):264-270.

- Barańska-Rybak W, Cubała WJ, Kozicka D, Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Nowicki R, Roszkiewicz J. Dermatitis artefacta–a long way from the first clinical symptoms to diagnosis. Psychiatr Danub 2011 Mar;23(1):73-75.

- Joe EK, Li VW, Magro CM, Arndt KA, Bowers KE. Diagnostic clues to dermatitis artefacta. Cutis 1999 Apr;63(4):209-214.

- Koblenzer CS. Psychological Aspects of Skin Disease. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, Freedberg IM, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI editor. Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. p. 475-486.

- Sneddon I, Sneddon J. Self-inflicted injury: a follow-up study of 43 patients. Br Med J 1975 Aug;3(5982):527-530.

- Wojewoda K, Brenner J, Kąkol M, Naesström M, Cubała WJ, Kozicka D, et al. A cry for help, do not omit the signs. Dermatitis artefacta–psychiatric problems in dermatological diseases (a review of 5 cases). Med Sci Monit 2012 Oct;18(10):CS85-CS89.

- Lyell A. Cutaneous artifactual disease. A review, amplified by personal experience. J Am Acad Dermatol 1979 Nov;1(5):391-407.

- Ehsani AH, Toosi S, Mirshams Shahshahani M, Arbabi M, Noormohammadpour P. Psycho-cutaneous disorders: an epidemiologic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009 Aug;23(8):945-947.