Pathogenic mutations in the C19orf12 gene result in a rare autosomal recessive condition, mitochondrial membrane protein-associated neurodegeneration (MPAN),1 part of the type 4 neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) group of disorders (MIM#614298).

Although several of the predominant features of MPAN may help distinguishing it from other forms of NBIA, no non-molecular test can reliably distinguish MPAN from other NBIA disorders. The diagnosis of MPAN is confirmed only in individuals with biallelic pathogenic variants in C19orf12, the only gene in which pathogenic variants are known to cause the condition. However, MPAN represents only about 5% of NBIA subtypes. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), account for up to 50% of cases, and are most commonly caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the PANK2 gene.1,2 Other subtypes of NBIA include neuroferritinopathy and aceruloplasminemia caused by mutations in the ferritin light chain (FTL) and mutations in the ceruloplasmin (CP) gene, respectively.3 Knowledge of the pattern of mutations among the Middle Eastern population is limited. We report the case of an Omani family with MPAN due to a novel deletion mutation in exon 2 of the C19orf12 gene, adding to our limited knowledge on the pattern of mutations in MPAN patients among the Middle Eastern population.

Case report

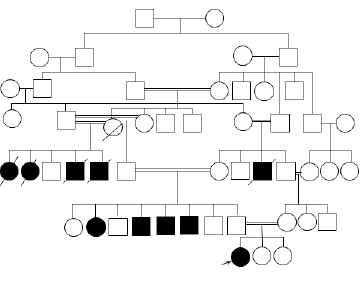

Figure 1: The pedigree of the family showing the affected individuals.

A previously well seven-year-old Omani girl with normal developmental milestones presented with a history of frequent falls for one year. Her birth history and past medical history were unremarkable. There was no history of change in her personality, and she had no learning difficulties.

Five individuals from both sides of the family, who were all offspring of consanguineous marriages, died of psychomotor regression. All had achieved normal developmental milestones until 9/10 years of age when they started to develop gait instability, slowly progressive cognitive impairments, severe generalized dystonia, and visual impairment. They became subsequently wheelchair bound and died in the fourth decade of life. In addition, four living relatives in their early 30s, three paternal uncles and one paternal aunt were affected [Figure 1]. When our patient was seen in the neurology clinic, no diagnosis was confirmed in any of the affected individuals.

On examination, she was well oriented (to place, time, and persons) and able to perform complex tasks appropriately. She had no dysmorphic features or neurocutaneous lesions. She had normal examination of the fundus and cranial nerves. Motor examination revealed a mild increase in the tone of the lower limbs. She had brisk, deep tendon reflexes in the lower limbs with bilateral equivocal planter response. There was sustained clonus bilaterally. She had difficulties with tandem gait. Sensory examinations were normal. Romberg’s sign was negative.

Figure 2: (a) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the brain. (b) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image showing hyperintensity in the anterior medial aspect of globus pallidus surrounded by hypointensities (“eye of tiger” sign). (c) Axial T2-weighted image showing hypointensity secondary to iron deposition involving bilateral substantia nigra and red nuclei.

The following investigations were performed and were all normal: urine organic acids, serum amino acids, tandem mass spectrometry, serum copper, serum CP, 24-hour urinary copper level, complete blood count, serum iron, and ferritin level. Nerve conduction study and ophthalmology assessment were also normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed iron deposition on the basal ganglia (T2 hypointensity in globus pallidus bilaterally) [Figure 2].

The ATP13A2, C19orf12, CP, FA2H, FTL, PANK2, and PLA2G6 genes were analyzed from blood sample using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing of both strands of the entire coding region and the highly conserved exon-intron splice junctions. Next-generation sequencing was done via an amplicon-based approach using the Roche 454 genome sequencer. No pathogenic mutation was detected in any of the genes; however, after few repetitions of C19orf12 exon 2 sequence analysis, the results were not obtainable, indicating a possible deletion of C19orf12 exon 2. This was detected using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) of the DNA. The heterozygosity of the deletion was confirmed in the proband’s parents and two healthy paternal uncles. Moreover, homozygosity of the deletion was confirmed in one of the affected paternal uncles.

Discussion

The presence of several known gene mutations and undiscovered genes that might lead to heterogeneous NBIA phenotypes as well as the phenotypic overlap between different types of NBIA, all make diagnosis a challenge.3,4

The presence of some radiological features in NBIA such as the “eye of the tiger” sign,1,5 might be helpful in diagnosing a specific NBIA subtype. The eye of the tiger sign was detected in our patient but has rarely been reported in C19orf12 related NBIAs. One study analyzed brain MRIs of 26 patients with genetically confirmed PKAN, 21 patients with neuroferritinopathy, 10 patients with aceruloplasminemia, and four patients with NBIA type 2. All patients with PKAN had the eye of the tiger sign, but this was only seen in two patients with neuroferritinopathy and none of the patients with aceruloplasminemia and NBIA type 2.6 In a cohort of 24 NBIA patients with C19orf12 gene defect, the eye of the tiger sign was only present in one patient.1 This indicates that the detection of this radiological sign does not support the approach of screening for mutations in the PANK2 gene exclusively, and mutations in the C19orf12 gene might be sought based on the clinical presentation.

A Polish cohort study identified frameshift and missense mutations in the C19orf12 gene.1 In our patient, we detected a novel gene mutation; homozygous deletion of exon 2 of the C19orf12 gene. C19orf12 is a small gene that spans less than 17 kb of the genomic sequence and codes for two protein isoforms of 141 and 152 amino acid residues in humans. The protein is highly conserved because almost 60% of the amino acid residues are identical between the human and zebrafish.1 The function of C19orf12 remains uncertain, but it may be involved in mitochondrial function, lipid homeostasis, and coenzyme A metabolism. Expression of the gene increases with differentiation of adipocytes along with genes involved in valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation and fatty acid metabolism.1 Based on the literature review, PubMed search, and Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD), this mutation has not been previously reported. Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of genetically confirmed NBIA in Oman. Since PANK2 gene mutations have never been reported in the Omani population, there is a need to determine the proportion of PANK2 and C19orf12 gene mutations among Omani patients with NBIA.

Although there are heterogeneous NBIA phenotypes due to different gene mutations, some clinical features remain consistent such as progressive dystonia, dysarthria, and rigidity. As previously described, gait instability is the initial presentation in most patients with MPAN.1 The age of onset in patients with MPAN is between four and 30 years with an average age of presentation of 11 years,1,7 in line with the presentation of the affected individual presented in this report.

Conclusion

Most of the genetically defined types of NBIA are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. We would expect a higher prevalence among populations with a high rate of consanguinity, such as Omani and other Middle Eastern populations. Unless the picture of contribution of each of the genes implicated in NBIA is clear and the pattern of mutations in the common genes is known, the diagnosis of specific genetic etiology of NBIA cases will remain a challenge and may not be a cost effective approach. Identifying familial mutations is important in Omani families to implement cost-effective methods to perform cascade screening of carriers at risk and address risky consanguineous marriages.

Disclosure

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient and her family for their informed consent and permission for publishing this report.

references

- Hartig MB, Iuso A, Haack T, Kmiec T, Jurkiewicz E, Heim K, et al. Absence of an orphan mitochondrial protein, c19orf12, causes a distinct clinical subtype of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Am J Hum Genet 2011 Oct;89(4):543-550.

- Zhou B, Westaway SK, Levinson B, Johnson MA, Gitschier J, Hayflick SJ. A novel pantothenate kinase gene (PANK2) is defective in Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome. Nat Genet 2001 Aug;28(4):345-349.

- Schneider SA, Hardy J, Bhatia KP. Syndromes of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA): an update on clinical presentations, histological and genetic underpinnings, and treatment considerations. Mov Disord 2012 Jan;27(1):42-53.

- Kurian MA, McNeill A, Lin JP, Maher ER. Childhood disorders of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). Dev Med Child Neurol 2011 May;53(5):394-404.

- Fermin-Delgado R, Roa-Sanchez P, Speckter H, Perez-Then E, Rivera-Mejia D, Foerster B, et al. Involvement of globus pallidus and midbrain nuclei in pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration: measurement of T2 and T2* time. Clin Neuroradiol 2013 Mar;23(1):11-15.

- McNeill A, Birchall D, Hayflick SJ, Gregory A, Schenk JF, Zimmerman EA, et al. T2* and FSE MRI distinguishes four subtypes of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Neurology 2008 Apr;70(18):1614-1619.

- Hogarth P, Gregory A, Kruer MC, Sanford L, Wagoner W, Natowicz MR, et al. New NBIA subtype: genetic, clinical, pathologic, and radiographic features of MPAN. Neurology 2013 Jan;80(3):268-275.